Cowboy

Cowgirls, first defined as such in the late 19th century, had a less-well documented historical role, but in the modern world work at identical tasks and have obtained considerable respect for their achievements.

Over the centuries, differences in terrain and climate, and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures, created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling.

Claudius Smith, an outlaw identified with the Loyalist cause, was called the "Cow-boy of the Ramapos" due to his penchant for stealing oxen, cattle and horses from colonists and giving them to the British.

[16][17] The San Francisco Examiner wrote in an editorial, "Cowboys [are] the most reckless class of outlaws in that wild country ... infinitely worse than the ordinary robber.

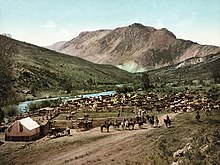

Both regions possessed a dry climate with sparse grass, thus large herds of cattle required vast amounts of land to obtain sufficient forage.

[20] During the 16th century, the Conquistadors and other Spanish settlers brought their cattle-raising traditions as well as both horses and domesticated cattle to the Americas, starting with their arrival in what today is Mexico and Florida.

Before the Mexican–American War in 1848, New England merchants who traveled by ship to California encountered both hacendados and vaqueros, trading manufactured goods for the hides and tallow produced from vast cattle ranches.

Particularly with the arrival of railroads and an increased demand for beef in the wake of the American Civil War, older traditions combined with the need to drive cattle from the ranches where they were raised to the nearest railheads, often hundreds of miles away.

It was common practice in the west for young foals to be born of tame mares, but allowed to grow up "wild" in a semi-feral state on the open range.

Other cowboys recognized their need to treat animals in a more humane fashion and modified their horse training methods,[41] often re-learning techniques used by the vaqueros, particularly those of the Californio tradition.

Farmers in eastern Kansas, afraid that Longhorns would transmit cattle fever to local animals as well as trample crops, formed groups that threatened to beat or shoot cattlemen found on their lands.

[53] By the 1890s, barbed-wire fencing was also standard in the northern plains, railroads had expanded to cover most of the nation, and meat packing plants were built closer to major ranching areas, making long cattle drives from Texas to the railheads in Kansas unnecessary.

By the late 1860s, following the American Civil War and the expansion of the cattle industry, former soldiers from both the Union and Confederacy came west, seeking work, as did large numbers of restless white men in general.

The average cowboy earned approximately a dollar a day, plus food, and, when near the home ranch, a bed in the bunkhouse, usually a barracks-like building with a single open room.

[60] Over time, the cowboys of the American West developed a personal culture of their own, a blend of frontier and Victorian values that even retained vestiges of chivalry.

Such hazardous work in isolated conditions also bred a tradition of self-dependence and individualism, with great value put on personal honesty, exemplified in songs and poetry.

While impractical for everyday work, the sidesaddle was a tool that afforded women the ability to ride horses in public settings instead of being left on foot or confined to horse-drawn vehicles.

The California vaquero or buckaroo, unlike the Texas cowboy, was considered a highly skilled worker, who usually stayed on the same ranch where he was born or had grown up and raised his own family there.

[88] Following the American Civil War, vaquero culture combined with the cattle herding and drover traditions of the southeastern United States that evolved as settlers moved west.

Historian Terry Jordan proposed in 1982 that some Texan traditions that developed—particularly after the Civil War—may trace to colonial South Carolina, as most settlers to Texas were from the southeastern United States.

The hides and meat from Florida cattle became such a critical supply item for the Confederacy during the American Civil War that a unit of Cow Cavalry was organized to round up and protect the herds from Union raiders.

By 1837 John Parker, a sailor from New England who settled in the islands, received permission from Kamehameha III to lease royal land near Mauna Kea, where he built a ranch.

The working cowboy usually is in charge of a small group or "string" of horses and is required to routinely patrol the rangeland in all weather conditions checking for damaged fences, evidence of predation, water problems, and any other issue of concern.

A good stock horse is on the small side, generally under 15.2 hands (62 inches) tall at the withers and often under 1000 pounds, with a short back, sturdy legs and strong muscling, particularly in the hindquarters.

Sturdy and roomy, with a high ground clearance, and often four-wheel drive capability, it has an open box, called a "bed", and can haul supplies from town or over rough trails on the ranch.

Exhibitions such as those of Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show helped to popularize the image of the cowboy as an idealized representative of the tradition of chivalry.

In the United States, the Canadian West and Australia, guest ranches offer people the opportunity to ride horses and get a taste of the western life—albeit in far greater comfort.

Many other people, particularly in the West, including lawyers, bankers, and other white collar professionals wear elements of Western clothing, particularly cowboy boots or hats, as a matter of form even though they have other jobs.

Conversely, some people raised on ranches do not necessarily define themselves cowboys or cowgirls unless they feel their primary job is to work with livestock or if they compete in rodeos.

[7] "Cowboy" is sometimes used today in a derogatory sense to describe someone who is reckless or ignores potential risks, irresponsible or who heedlessly handles a sensitive or dangerous task.