Frederic Remington

He then transferred to another military school where his classmates found the young Remington to be a pleasant fellow, a bit careless and lazy, good-humored, and generous of spirit but definitely not soldier material.

From that first trip, Harper's Weekly printed Remington's first published commercial effort, a re-drawing of a quick sketch on wrapping paper that he had mailed back east.

He invested his entire inheritance but found ranching to be a rough, boring, isolated occupation which deprived him of the finer things he was used to from East Coast life, and the real ranchers thought of him as lazy.

After acquiring more capital from his mother, he returned to Kansas City to start a hardware business, but due to an alleged swindle, it failed, and he reinvested his remaining money as a silent, half-owner of a saloon.

[28] The 29-year-old Roosevelt had a similar Western adventure to Remington, losing money on a ranch in North Dakota the previous year but gaining experience which made him an "expert" on the West.

His full-color oil painting Return of the Blackfoot War Party was exhibited at the National Academy of Design and the New York Herald commented that Remington would "one day be listed among our great American painters".

[31] Remington's regular attendance at celebrity banquets and stag dinners, however, though helpful to his career, fostered prodigious eating and drinking which caused his girth to expand alarmingly.

The community was close to New York City affording easy access to the publishing houses and galleries necessary for the artist, and also rural enough to provide him with the space he needed for horseback riding, and other physical activities that relieved the long hours of concentration required by his work.

[33] In the early years, no real studio existed at Endion and Remington did most of his work in a large attic under the home's front gable where he stored materials collected on his many western excursions.

Remington himself wrote to his friend the novelist Owen Wister:[34] Have concluded to build a butler's pantry and a studio (Czar size) on my house—we will be torn [up] for a month and then will ask you to come over—throw your eye on the march of improvement and say this is a great thing for American art.

He was invited out West to make their portraits in the field and to gain them national publicity through Remington's articles and illustrations for Harper's Weekly, particularly General Nelson Miles, an Indian fighter who aspired to the presidency of the United States.

"[35] Remington arrived on the scene just after the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, in which 150 Sioux, mostly women and children, were killed.

Through the 1890s, Remington took frequent trips around the US, Mexico, and abroad to gather ideas for articles and illustrations, but his military and cowboy subjects always sold the best, even as the Old West was playing out.

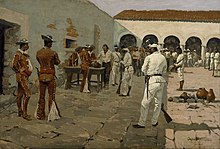

"[31] Remington's focus continued on outdoor action and he rarely depicted scenes in gambling and dance halls typically seen in Western movies.

[40] With help from friend and sculptor Frederick Ruckstull, Remington constructed his first armature and clay model, a "broncho buster" on a horse that was rearing on its hind legs—technically a very challenging subject.

Remington was ecstatic about his new line of work, and though critical response was mixed, some labelling it negatively as "illustrated sculpture", it was a successful first effort earning him $6,000 over three years.

[43] Sensing the political mood of that time, he was looking forward to a military conflict which would provide the opportunity to be a heroic war correspondent, giving him both new subject matter and the excitement of battle.

[43] Remington kept up his contact with celebrities and politicos, and continued to woo Theodore Roosevelt, now the New York City Police Commissioner, by sending him complimentary editions of new works.

[45] Remington's association with Roosevelt paid off, however, when the artist was hired as a war correspondent and illustrator for William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal in January 1897.

Aboard the ship, he met Clemencia Arango, who said her brother was a colonel in the insurgence, that she had been deported for her revolutionary activities, and that she had been stripsearched by the Spanish officials before boarding.

The front page of the Journal for the 12th was dominated by Remington's sensationalist illustration, run across five columns of newsprint, of Arango stripped naked on the ship's deck, in public, surrounded by four male Spanish officials.

The issue sold a record number of copies, almost a million, partly on the strength of Remington's image of a naked humiliated female resistance fighter.

"[46] As he witnessed the assault on San Juan Hill by American forces, including those led by Roosevelt, his heroic conception of war was shattered by the actual horror of jungle fighting and the deprivations he faced in camp.

[48] When the Rough Riders returned to the US, they presented their courageous leader Roosevelt with Remington's bronze statuette, The Bronco Buster, which the artist proclaimed, "the greatest compliment I ever had.... After this everything will be mere fuss."

To compensate for the loss of work, Remington wrote and illustrated a full-length novel, The Way of an Indian, which was intended for serialization by a Hearst publication but was not published until five years later in Cosmopolitan.

In his final two years, under the influence of The Ten, he was veering more heavily to Impressionism, and he regretted that he was studio bound (by virtue of his declining health) and could not follow his peers, who painted "plein air".

His extreme obesity (of nearly 300 lbs = 136,1 kgs) had complicated the anesthesia and the surgery, and chronic appendicitis was cited in the postmortem examination as an underlying factor in his death.

His collaboration with Owen Wister on The Evolution of the Cowpuncher, published by Harper's Monthly in September 1893, was the first statement of the mythical cowboy in American literature, spawning the entire genre of Western fiction, films, and theater that followed.

)[69] Remington was one of the first American artists to illustrate the true gait of the horse in motion (along with Thomas Eakins), as validated by the famous sequential photographs of Eadweard Muybridge.

The galloping horse became Remington's signature subject, which was copied and interpreted by many Western artists who followed him to adopt the correct anatomical motion.