Crab claw sail

It may have also caused the unique development of outrigger boat technology due to the necessity for stability once crab claw sails were attached to small watercraft.

[3] Crab claw sails can be used for double-canoe (catamaran), single-outrigger (on the windward side), or double-outrigger boat configurations, in addition to monohulls.

[4][5] Crab claw sails are rigged fore-and-aft and can be tilted and rotated relative to the wind.

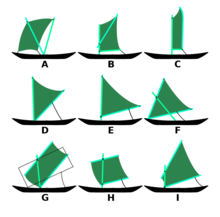

They evolved from "V"-shaped perpendicular square sails (a "double sprit") in which the two spars converge at the base of the hull.

In addition to the unique invention of outriggers to solve this, the sails were also leaned backwards and the converging point moved further forward on the hull.

This new configuration required a loose "prop" in the middle of the hull to hold the spars up, as well as rope supports on the windward side.

This allowed more sail area (and thus more power) while keeping the center of effort low and thus making the boats more stable.

The prop was later converted into fixed or removable canted masts where the spars of the sails were actually suspended by a halyard from the masthead.

Micronesian, Island Melanesian, and Polynesian single-outrigger vessels also used this canted mast configuration to uniquely develop shunting, where canoes are symmetrical from front to back and change end-to-end when sailing against the wind.

[3][6] Another evolution of the basic crab claw sail is the conversion of the upper spar into a fixed mast.

[3][6] Austronesians traditionally made their sails from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant pandanus leaves.

The failure of pandanus to establish populations in Easter Island and New Zealand is believed to have isolated their settlements from the rest of Polynesia.

The crab claw characteristically widens upwards, putting more sail area higher above the ocean, where the wind is stronger and steadier.

In a shunt, the sail is unfixed from the bow, the other side of it is fixed to the stern, and the mast rake is also reversed.

The vessel therefore always has the ama outrigger (and sidestay, if there is one) to windward, and has no bad tack, traveling equally well in both directions.

To tack, or switch directions across the wind, the forward corner of the sail is loosened and then transferred to the opposite end of the boat, a process called shunting.

[21][22] A more modern academic wind tunnel study (2014) provided similar results, with the Santa Cruz Islands tepukei's crab claw sail configuration dominating measurements.

- Double sprit ( Sri Lanka )

- Common sprit ( Philippines )

- Oceanic sprit ( Tahiti )

- Oceanic sprit ( Marquesas )

- Oceanic sprit ( Philippines )

- Crane sprit ( Marshall Islands )

- Rectangular boom lug ( Maluku Islands )

- Square boom lug ( Gulf of Thailand )

- Trapezial boom lug ( Vietnam )