Crab Nebula

The common name comes from a drawing that somewhat resembled a crab with arms produced by William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, in 1842 or 1843 using a 36-inch (91 cm) telescope.

[8] At an apparent magnitude of 8.4, comparable to that of Saturn's moon Titan, it is not visible to the naked eye but can be made out using binoculars under favourable conditions.

At X-ray and gamma ray energies above 30 keV, the Crab Nebula is generally the brightest persistent gamma-ray source in the sky, with measured flux extending to above 10 TeV.

[d][9] This eventually led to the conclusion that the creation of the Crab Nebula corresponds to the bright SN 1054 supernova recorded by medieval astronomers in AD 1054.

[12] William Herschel observed the Crab Nebula numerous times between 1783 and 1809, but it is not known whether he was aware of its existence in 1783, or if he discovered it independently of Messier and Bevis.

[13] William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse observed the nebula at Birr Castle in the early 1840s using a 36-inch (0.9 m) telescope, and made a drawing of it that showed it with arms like those of a crab.

[9] That same year, John Charles Duncan demonstrated that the remnant was expanding,[18] while Knut Lundmark noted its proximity to the guest star of 1054.

[26][27] Recent analysis of historical records have found that the supernova that created the Crab Nebula probably appeared in April or early May, rising to its maximum brightness of between apparent magnitude −7 and −4.5 (brighter even than Venus' −4.2 and everything in the night sky except the Moon) by July.

In late 1968, David H. Staelin and Edward C. Reifenstein III reported the discovery of two rapidly variable radio sources in the area of the Crab Nebula using the Green Bank Telescope.

The period of 33 milliseconds and precise location of the Crab Nebula pulsar NP 0532 was discovered by Richard V. E. Lovelace and collaborators on 10 November 1968 at the Arecibo Radio Observatory.

The only possible exception to this rule would be SN 1181, whose supposed remnant 3C 58 is home to a pulsar, but its identification using Chinese observations from 1181 is contested.

[5] The Crab Nebula was the first astrophysical object confirmed to emit gamma rays in the very-high-energy (VHE) band above 100 GeV in energy.

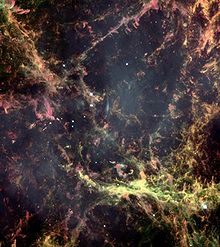

[4] The filaments are the remnants of the progenitor star's atmosphere, and consist largely of ionised helium and hydrogen, along with carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, iron, neon and sulfur.

In the 1960s it was found that the source of the curved paths of the electrons was the strong magnetic field produced by a neutron star at the centre of the nebula.

In 1973, an analysis of many methods used to compute the distance to the nebula had reached a conclusion of about 1.9 kpc (6,300 ly), consistent with the currently cited value.

The amount of matter contained in the Crab Nebula's filaments (ejecta mass of ionized and neutral gas; mostly helium[48]) is estimated to be 4.6±1.8 M☉.

[49] One of the many nebular components (or anomalies) of the Crab Nebula is a helium-rich torus which is visible as an east–west band crossing the pulsar region.

[51] The region around the star was found to be a strong source of radio waves in 1949[52] and X-rays in 1963,[53] and was identified as one of the brightest objects in the sky in gamma rays in 1967.

[55] However, the discovery of a pulsating radio source in the centre of the Crab Nebula was strong evidence that pulsars were formed by supernova explosions.

[56] They now are understood to be rapidly rotating neutron stars, whose powerful magnetic fields concentrates their radiation emissions into narrow beams.

Occasionally, its rotational period shows sharp changes, known as 'glitches', which are believed to be caused by a sudden realignment inside the neutron star.

The rate of energy released as the pulsar slows down is enormous, and it powers the emission of the synchrotron radiation of the Crab Nebula, which has a total luminosity about 148,000 times greater than that of the Sun.

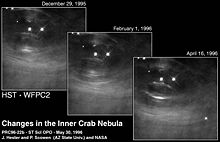

[60] The pulsar's extreme energy output creates an unusually dynamic region at the centre of the Crab Nebula.

[65] Recent studies, however, suggest the progenitor could have been a super-asymptotic giant branch star in the 8 to 10 M☉ range that would have exploded in an electron-capture supernova.

Variations in the radio waves received from the Crab Nebula at this time can be used to infer details about the corona's density and structure.