Guild

They sometimes depended on grants of letters patent from a monarch or other ruler to enforce the flow of trade to their self-employed members, and to retain ownership of tools and the supply of materials, but most were regulated by the local government.

[10] Following the passage of the Lex Julia in 45 BC, and its reaffirmation during the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 BC–14 AD), collegia required the approval of the Roman Senate or the emperor in order to be authorized as legal bodies.

[12] In September 2011, archeological investigations done at the site of an artificial harbor in Rome, the Portus, revealed inscriptions in a shipyard constructed during the reign of Trajan (98–117) indicating the existence of a shipbuilders guild.

[21] Early egalitarian communities called "guilds"[22] were denounced by Catholic clergy for their "conjurations" — the binding oaths sworn among the members to support one another in adversity, kill specific enemies, and back one another in feuds or in business ventures.

[23] In the Early Middle Ages, most of the Roman craft organisations, originally formed as religious confraternities, had disappeared, with the apparent exceptions of stonecutters and perhaps glassmakers, mostly the people that had local skills.

Gregory of Tours tells a miraculous tale of a builder whose art and techniques suddenly left him, but were restored by an apparition of the Virgin Mary in a dream.

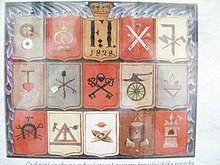

"[25] There were different guilds of metal-workers: the farriers, knife-makers, locksmiths, chain-forgers, nail-makers, often formed separate and distinct corporations; the armourers were divided into helmet-makers, escutcheon-makers, harness-makers, harness-polishers, etc.

The guild system reached a mature state in Germany c. 1300 and held on in German cities into the 19th century, with some special privileges for certain occupations remaining today.

In France, a resurgence of the guilds in the second half of the 17th century is symptomatic of Louis XIV and Jean Baptiste Colbert's administration's concerns to impose unity, control production, and reap the benefits of transparent structure in the shape of efficient taxation.

[33] The guilds were identified with organizations enjoying certain privileges (letters patent), usually issued by the king or state and overseen by local town business authorities (some kind of chamber of commerce).

Controls on the association of physical locations to well-known exported products, e.g. wine from the Champagne and Bordeaux regions of France, tin-glazed earthenwares from certain cities in Holland, lace from Chantilly, etc., helped to establish a town's place in global commerce — this led to modern trademarks.

On the other hand, Ogilvie agrees, guilds created "social capital" of shared norms, common information, mutual sanctions, and collective political action.

The exclusive privilege of a guild to produce certain goods or provide certain services was similar in spirit and character to the original patent systems that surfaced in England in 1624.

These systems played a role in ending the guilds' dominance, as trade secret methods were superseded by modern firms directly revealing their techniques, and counting on the state to enforce their legal monopoly.

While this was the overarching practice, there were guilds and professions that did allow women's participation, and the Medieval era was an ever-changing, mutable society—especially considering that it spanned hundreds of years and many different cultures.

In a study of London silkwomen of the 15th century by Marian K. Dale, she notes that medieval women could inherit property, belong to guilds, manage estates, and run the family business if widowed.

Crowston notes that the decline thesis has been reaffirmed in the German context by Wiesner and Ogilvie, but that it does not work in looking at the matter from a larger scope, as her expertise is in French history.

[54] In July 1706, a group of women, members of the Parisian wigmakers, went to Versailles in order to petition Louis XIV to remove a stifling tax that had been levied on wigs that same year.

When they entered guilds, seamstresses in Paris, Rouen, and Aix-en-Provence acquired the right to make articles of clothing for women and children, but not for men or boys over age eight.

[citation needed] Though most guilds died off by the middle of the nineteenth century, quasi-guilds persist today, primarily in the fields of law, medicine, engineering, and academia.

In America a number of interested parties sought to emulate the model of apprenticeship which European guilds of the Middle Ages had honed to achieve their ends of establishing exclusivity in trades[63][64] as well as the English concept of a gentleman which had come to be associated with higher income and craftsmanship[65][62][66] Licensing and accreditation practices which typically result from the lobbying of professional associations constitute the modern equivalent of a 'guild-privilege', albeit in contrast to guilds of the Middle Ages which held a letters patent which explicitly granted them monopolies on the provision of services, today's quasi-guild privileges are subtler, more complex, and less directly restrictive to consumers in their nature.

Nevertheless, it can be argued quasi-guild privileges are in many cases designed not just to serve some notion of public good, but to facilitate the establishing and maintaining of exclusivity in a field of work.

There are often subtle dichotomies present in attempting to answer the question of whether modern licensing and accreditation practices are intended to serve the public good, however it be defined.

'Universitas' in the Middle Ages meant a society of masters who had the capacity for self-governance, and this term was adopted by students and teachers who came together in the twelfth century to form scholars guilds.

It is as if an organization decided which automobiles would be allowed to be sold by checking to make sure that each car model had tires, doors, an engine and so forth and had been assembled by workers with proper training—but without actually driving any cars" - George C. Leef and Roxana D. Burris, Can College Accreditation Live Up To Its Promise?Taken in the context of guilds, it can be argued that the purpose of accreditation is to provide a mechanism for members of the scholars guild to protect itself, both by limiting outsiders from entering the field and by enforcing established norms onto one another.

Contriving means to limit the number of outsiders who gain an entrance to a field (exclusivity) and to enforce work norms among members were both distinguishing feature of guilds in the Middle Ages.

According to Piketty, the falsity of such claims is that the specific breakthrough which allowed for the development of these GMO seeds was in fact only the outcome of generations of public investment in education and research.

The City of London livery companies maintain strong links with their respective trade, craft or profession, some still retain regulatory, inspection or enforcement roles.

"City and Guilds" operates as an examining and accreditation body for vocational, managerial and engineering qualifications from entry-level craft and trade skills up to post-doctoral achievement.

In September 2005 the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against the National Association of Realtors, challenging NAR practices that (the DOJ asserted) prevent competition from practitioners who use different methods.