Crimes Act of 1825

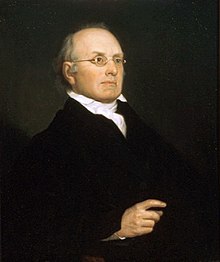

[4] Although the common law crimes approach was rejected by the Supreme Court,[5] "[w]hat Story was not able to do as a Justice he remedied through his friendship with Webster, then Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

[8] Story drafted the act with the assistance of Representative Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, a frequent Supreme Court advocate.

[2] Representative Charles A. Wickliffe of Kentucky objected to the extension of the death penalty to crimes other than treason, rape, and murder.

[2] Representatives William Cox Ellis, James Buchanan, and Edward Livingston concurred with Wickliffe.

[6] In effect, the Crimes Act of 1825 amplified the definition of "high seas" to include "any river, haven, creek, basin, or bay, within the admiralty and maritime jurisdiction of the United States.

[18] In United States v. Germaine (1878), the Waite Court held that the extortion under color of office offense applied only to defendants who were officers of the United States within the meaning of the Appointments Clause of Article Two.

Section 23 made maritime insurance fraud punishable by 3 years hard labor and a $3000 fine.

[25]) In dicta in Coombs, Justice Story explained that this provision (which he had penned) "is also derived from the power to regulate commerce.

Section 14 also re-enacted the venue provision of § 8 of the Crimes Act of 1790, with minor changes in wording.

[27] Section 8 of the 1790 Act had provided that "the trial of crimes committed on the high seas, or in any place out of the jurisdiction of any particular state, shall be in the district where the offender is apprehended, or into which he may first be brought.

[29] Previously, a Congressional resolution accompanying the Crimes Act of 1790 had requested that the state make their prisons available to federal convicts.

[30] "[F]rom 1825 until the close of the Civil War, the few additions to the list of statutory crimes which were made broke little new ground.