British credit crisis of 1772–1773

Accompanying the more tangible evidence of wealth creation was a rapid expansion of credit and banking, leading to a rash of speculation and dubious financial innovation (venture capitalism).

[3] In June 1772 Alexander Fordyce lost £300,000 shorting East India Company stock, leaving his partners Henry Neale, William James, and Richard Down liable for an estimated £243,000 in debts.

[5][6] According to Paul Kosmetatos "lurid tales abounded in the press for a time of merchants cutting their throats, shooting or hanging themselves".

[3] The credit boom came to an abrupt end, and the ensuing crisis harmed the East India Trading Company, the West Indies in general, and the North American colonial planters specifically.

[8] From the mid-1760s to the early 1770s, the credit boom, supported by merchants and bankers, facilitated the expansion of manufacturing, mining, and internal improvements in both Britain and the thirteen colonies.

As a result of the Townshend Act and the breakdown of the Boston Non-importation agreement, the period was marked by tremendous growth in exports from Britain to the American colonies.

[9] Problems, however, lay behind the credit boom and the prosperity of both British and colonial economies as speculation and the establishment of dubious financial institutions rose.

For example, in Scotland, bankers adopted "the notorious practice of drawing and redrawing fictitious bills of exchange...in an effort to expand credit".

The warning signals of the impending crisis, such as overstocked shelves and warehouses in the colonies, were overlooked by British merchants and American planters.

[1] In July 1770 Alexander Fordyce collaborated with two planters on Grenada and borrowed 240,000 guilders in bearer bonds from Hope & Co. in Amsterdam; he was backed by Harman and Co. and Sir William Pulteney.

[20] His goods and estate were seized and Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down, the largest buyer of Scottish bills, were forced to insolvency.

So great are the losses and inconveniences sustained by many individuals from a late bankruptcy, that a great number of eminent merchants and gentlemen of fortune at a meeting held for that purpose, have come to resolution not to keep their cash at any Bank, who jointly or separately by themselves or agents, are known to sport in the alley in what are called bulls or bears, since by one unlucky stroke in this illegal traffic, usually called speculation, hundreds of their creditors may be ruined; a species of gaming that can no more be justified in persons so largely intrusted with the property of others, than that of gambling at the hazard tables.

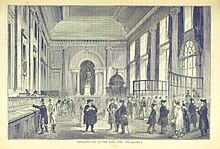

As confidence started ebbing, paralysis of the credit system followed: crowds of creditors gathered at the banks and requested debt repayment in cash or attempted to withdraw their deposits.

[23] At that time, the Gentleman's Magazine commented, "No event for 50 years past has been remembered to have given so fatal a blow both to trade and public credit".

[32] By 1772 the Ayr bank had branches in Edinburgh and Dumfries, as well as representative offices in Glasgow, Inverness, Kelso, Montrose, Campbeltown, and several other places.

[41] The negotiations set up by the Cliffords in Surinam, the Van Seppenwoldes, Ter Borch, Hope & Co on Grenada, Sint Eustatius, and Saint Croix issued bonds to finance the loans.

Such packages could contain loans to 20 or more plantations, and before 1772, at least 40 of these bundles were issued, their names as unspecific as L.a. A, B or C. Investors thus had little knowledge of what they invested in, and lent their money purely on good faith and the word of the fund director.

[42] In December 1772 Clifford & Co, a well established Amsterdam banking firm which obtained plantation loans as part of its portfolio declared insolvency.

[45][46] The merchant banking firm Clifford & Sons broke eventually, followed by more of its counterparts like Herman & Johan van Seppenwolde and Abraham Ter Borch.

[49] In January 1773, Joshua Vanneck and his brother were involved by Thomas Walpole when British merchants sent £500,000, gold and piastre to Amsterdam.

The East India Company, once primarily a trading entity with a limited territory, found itself assigned to oversee a significantly larger region.

'[52] As leading Dutch banking houses (Andries Pels and Clifford & Son) had invested extensively in the stock of the East India Company, they suffered the loss along with the other shareholders.

[60] On 14 January 1773, the directors of the EIC asked for a government loan and unlimited access to the tea market in the American colonies, both of which were granted.

Failing to pay or renew its loan from the Bank of England, the firm sought to sell its eighteen million pounds of tea from its British warehouses to the American colonies.