Cross of Sacrifice

It was often impossible to dig trenches without unearthing remains, and artillery barrages often uncovered bodies and flung the disintegrating corpses into the air.

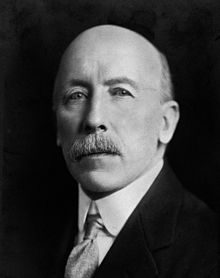

[4] Fabian Ware, a director of the Rio Tinto mining company, toured some battlefields in as part of a British Red Cross mission in the fall of 1914.

[5] Ware was greatly disturbed by status of British war graves, many of which were marked by deteriorating wooden crosses, haphazardly placed and with names and other identifying information written nearly illegibly in pencil.

Subsequently, as the war continued, there was a growing expectation among the people of the United Kingdom that foot soldiers as well as officers should not only be buried singly but commemorated.

Numerous letters appeared in newspapers decrying the problem, and Ware realized the British war effort was heading towards a public relations disaster.

[5][18] In July 1917,[18] after consulting with architectural and artistic experts in London,[14] Ware invited the architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker; Charles Aitken, director of the Tate Gallery; and the author Sir James Barrie to tour British battlefield cemeteries near the front in an attempt to formulate broad ideas for the post-war design of these burying grounds.

[23] Aitken insisted on cemeteries of simple design and low cost, feeling public money should be spent on practical items like schools and hospitals.

[22][24][b][25][26] At one point, Baker suggested a cross with a pentagonal shaft (one side for each self-governing dominion), and for Indian cemeteries a column topped by appropriate symbol (such as the dharmacakra or Star of India).

[27][c][28] Ware, Lutyens, and Baker met for a second time to discuss cemetery planning at the IWGC headquarters in London on 21 September 1917.

[14] Frustrated by the lack of agreement among and hardening positions adopted by Lutyens, Baker, and Aitken, Ware turned to Sir Frederic G. Kenyon, director of the British Museum and a highly respected ancient languages scholar.

He was also a lieutenant colonel in the British Army and had served in France, and he and Ware agreed to emphasize his military rank as a way of keeping disputes in check.

Over the next two months, Kenyon twice visited battlefield cemeteries in France and Belgium and consulted with a wide range of religious groups and artists.

[34] But he went a step further, and argued that the cemeteries should also be maintained in perpetuity by the British government, something never before attempted for large numbers of military graves.

[14][34] With Lutyens arguing for a "value free" and pantheistic Stone of Remembrance and Baker pushing for an elaborate and almost Neoclassical approach, Kenyon advocated a compromise solution.

When he lost that argument, he argued that the cross should have a shortened cross-arm and a lengthened shaft, in order to emphasize its verticality amidst the trees of the French countryside.

[40] After receiving the Kenyon report in February 1918, the following month Ware appointed Reginald Blomfield to be one of the senior architects overseeing the design of British war cemeteries.

Furthermore, Blomfield was a widely acknowledged expert in generating highly accurate cost estimates and in crafting excellent contracts.

[42] The same month he was appointed to the senior architects' committee, Blomfield accompanied Lutyens and Baker on a tour of French and Belgian battlefields.

His design, which he called the "Ypres cross", also included a bronze image of a naval sailing ship, emblematic of the Royal Navy's role in winning both the Crusades and the First World War.

"[45] Blomfield wanted a design that reflected the war, which had stripped away any notions about glory in combat and nobility in death on the battlefield.

"What I wanted to do in designing this Cross was to make it as abstract and impersonal as I could, to free it from any association of any particular style, and, above all, to keep clear of any sentimentalism of the Gothic.

[k][77] In the several Commonwealth cemeteries in the mountains of Italy, Blomfield's design was replaced with a Latin cross made of rough square blocks of red or white stone.

The artwork is susceptible to toppling in high wind, as the shaft is held upright only by a 6-inch (15 cm) long piece of stone and a single bronze dowel.

At one point, the Imperial War Graves Commission considered suing Blomfield for under-designing the artwork, but no lawsuit was ever filed.

Its enduring popularity, historian Allen Frantzen says, is because it is both simple and expressive, its abstraction reflecting the modernity people valued after the war.

Frantzen notes that the inverted sword is a common chivalrous emblem which can be seen as both an offensive and a defensive weapon, symbolizing might wielded in defence of the values of the cross; it here embodies "the ideals of simplicity and expressive functionalism".

"[86] First World War historian Bruce Scates observes that its symbolism was effective throughout the Commonwealth, despite widely disparate cultural and religious norms.

[92] The first Cross of Sacrifice to be erected after the Second World War was in the cemetery at Great Bircham, Norfolk, in the United Kingdom by George VI in July 1946.

[100] The inscription on the 24-foot (7.3 m) high gray granite cross is to "Citizens of the United States who served in the Canadian Army and gave their lives in the Great War".

[101] A Cross of Sacrifice stands in Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, Alabama and is the largest Commonwealth War Grave site in the United States.