Cross product

[3] The cross-product in seven dimensions has undesirable properties (e.g. it fails to satisfy the Jacobi identity), so it is not used in mathematical physics to represent quantities such as multi-dimensional space-time.

According to Sarrus's rule, this involves multiplications between matrix elements identified by crossed diagonals.

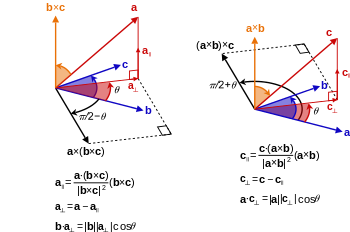

From this decomposition, by using the above-mentioned equalities and collecting similar terms, we obtain: meaning that the three scalar components of the resulting vector s = s1i + s2j + s3k = a × b are Using column vectors, we can represent the same result as follows: The cross product can also be expressed as the formal determinant:[note 1][1] This determinant can be computed using Sarrus's rule or cofactor expansion.

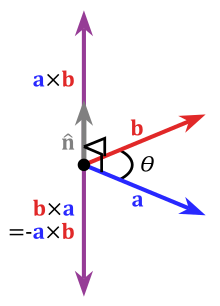

The magnitude of the cross product can be interpreted as the positive area of the parallelogram having a and b as sides (see Figure 1):[1]

Namely, since the dot product is defined, in terms of the angle θ between the two vectors, as: the above given relationship can be rewritten as follows: Invoking the Pythagorean trigonometric identity one obtains: which is the magnitude of the cross product expressed in terms of θ, equal to the area of the parallelogram defined by a and b (see definition above).

[13] For the cross product a × b = c, there are multiple b vectors that give the same value of c. As a result, it is not possible to rearrange this equation to yield a unique solution for b in terms of a and c. Nevertheless, it is possible to find a family of solutions for b, which are where t is an arbitrary constant.

This can be derived using the triple product expansion: Rearrange to solve for b to give The coefficient of the last term can be simplified to just the arbitrary constant t to yield the result shown above.

In the case where n = 3, combining these two equations results in the expression for the magnitude of the cross product in terms of its components:[15] The same result is found directly using the components of the cross product found from In R3, Lagrange's equation is a special case of the multiplicativity |vw| = |v||w| of the norm in the quaternion algebra.

In higher dimensions the product can still be calculated but bivectors have more degrees of freedom and are not equivalent to vectors.

This characterization of the cross product is often expressed more compactly using the Einstein summation convention as in which repeated indices are summed over the values 1 to 3.

In that case, this representation is another form of the skew-symmetric representation of the cross product: In classical mechanics: representing the cross product by using the Levi-Civita symbol can cause mechanical symmetries to be obvious when physical systems are isotropic.

(An example: consider a particle in a Hooke's Law potential in three-space, free to oscillate in three dimensions; none of these dimensions are "special" in any sense, so symmetries lie in the cross-product-represented angular momentum, which are made clear by the abovementioned Levi-Civita representation).

The cross product can be used to calculate the normal for a triangle or polygon, an operation frequently performed in computer graphics.

In computational geometry of the plane, the cross product is used to determine the sign of the acute angle defined by three points

It corresponds to the direction (upward or downward) of the cross product of the two coplanar vectors defined by the two pairs of points

The cross product is used to describe the Lorentz force experienced by a moving electric charge qe: Since velocity v, force F and electric field E are all true vectors, the magnetic field B is a pseudovector.

The trick of rewriting a cross product in terms of a matrix multiplication appears frequently in epipolar and multi-view geometry, in particular when deriving matching constraints.

When physics laws are written as equations, it is possible to make an arbitrary choice of the coordinate system, including handedness.

One should be careful to never write down an equation where the two sides do not behave equally under all transformations that need to be considered.

In general dimension, there is no direct analogue of the binary cross product that yields specifically a vector.

Generalizations to higher dimensions is provided by the same commutator product of 2-vectors in higher-dimensional geometric algebras, but the 2-vectors are no longer pseudovectors.

In the context of multilinear algebra, the cross product can be seen as the (1,2)-tensor (a mixed tensor, specifically a bilinear map) obtained from the 3-dimensional volume form,[note 2] a (0,3)-tensor, by raising an index.

In the same way, in higher dimensions one may define generalized cross products by raising indices of the n-dimensional volume form, which is a

If n is odd, this modification leaves the value unchanged, so this convention agrees with the normal definition of the binary product.

In 1773, Joseph-Louis Lagrange used the component form of both the dot and cross products in order to study the tetrahedron in three dimensions.

[24][note 3] In 1843, William Rowan Hamilton introduced the quaternion product, and with it the terms vector and scalar.

In 1853, Augustin-Louis Cauchy, a contemporary of Grassmann, published a paper on algebraic keys which were used to solve equations and had the same multiplication properties as the cross product.

In the book, this product of two vectors is defined to have magnitude equal to the area of the parallelogram of which they are two sides, and direction perpendicular to their plane.

[29][30] In 1901, Gibb's student Edwin Bidwell Wilson edited and extended these lecture notes into the textbook Vector Analysis.

[31] In 1908, Cesare Burali-Forti and Roberto Marcolongo introduced the vector product notation u ∧ v.[25] This is used in France and other areas until this day, as the symbol