Cuckoo clock

It is thought that much of its development and evolution was made in the Black Forest area in southwestern Germany (in the modern state of Baden-Württemberg), the region where the cuckoo clock was popularized and from where it was exported to the rest of the world, becoming world-famous from the mid-1850s on.

The weights are made of cast iron usually in a pine cone shape and the "cuckoo" sound is created by two tiny gedackt pipes in the clock, with bellows attached to their tops.

As with their mechanical counterparts, the cuckoo bird emerges from its enclosure and moves up and down, but often on the quartz timepieces it also flaps its wings and open its beak while it sings.

On quartz wall clocks in the traditional style, the weights are conventionally cast in the shape of pine cones made of plastic rather than iron.

In 1629, many decades before clockmaking was established in the Black Forest,[7] an Augsburg merchant by the name of Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647) penned one of the first known descriptions of a modern cuckoo clock.

For instance, the Historische Nachrichten (1713), an anonymous publication generally attributed to Court Preacher Bartholomäus Holzfuss, mentions a musical clock in the Oranienburg palace in Berlin.

By the middle of the 18th century, several small clockmaking shops between Neustadt and Sankt Georgen[17] were making cuckoo clocks out of wood and shields decorated with paper.

[18] After a journey through south-west Germany in 1762, Count Giuseppe Garampi, Prefect of the Vatican Archives, remarked: "In this region large quantities of wooden movement clocks are made, and even if they were not completely unknown earlier, they have now been perfected, and one has started to equip them with the cuckoo's call.

They are extremely rare, Wilhelm Schneider was only able to list a dozen of pieces with wooden movements in his book Frühe Kuckucksuhren (Early Cuckoo Clocks) (2008).

When they returned home, they brought with them this novelty, since it had caught their eyes, and show it to Michael Dilger from Neukirch and Matthäus Hummel from Glashütte, who were very pleased with it and began to copy it.

The second story is related by another priest, Markus Fidelis Jäck, in a passage extracted from his report Darstellungen aus der Industrie und des Verkehrs aus dem Schwarzwald (Descriptions of the Industry and Transport of the Black Forest), (1810) said as follows: "The cuckoo clock was invented (in the early 1730s) by a clock-master [Franz Anton Ketterer] from Schönwald.

This statement was corroborated by Gerd Bender in the most recent edition of the first volume of his work Die Uhrenmacher des hohen Schwarzwaldes und ihre Werke (The Clockmakers of the High Black Forest and their Works) (1998) in which he wrote that the cuckoo clock was not native to the Black Forest and also stated that: "There are no traces of the first production line of cuckoo clocks made by Ketterer".

Schaaf, in Schwarzwalduhren (Black Forest Clocks) (1995), provides his own research which leads to the earliest cuckoos having been built in the Franconia and Lower Bavaria area, in the southeast of Germany, (forming nowadays the northern two-thirds of the Free State of Bavaria), in the direction of Bohemia (nowadays the main region of the Czech Republic), which he notes, lends credence to the Steyrer version.

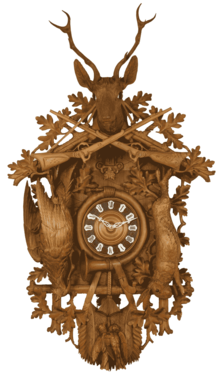

Even though the functionality of the cuckoo mechanism has remained basically unchanged, the appearance has changed as case designs and clock movements evolved in the region.

As the name suggests, these wall timepieces consisted of a picture frame, usually with a typical Black Forest scene painted on a wooden background or a sheet metal, lithography and screen-printing were other techniques used.

The painting was almost always protected by a glass and some models displayed a person or an animal with blinking or flirty eyes as well, being operated by a simple mechanism worked by means of the pendulum swinging.

[29] On the other hand, from the 1860s until the early 20th century, cases were manufactured in a wide variety of styles such as; Neoclassical or Georgian (certain pieces also displayed a painting), neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque, Art Nouveau, etc., becoming a suitable decorative object for the bourgeois home.

In September 1850, the first director of the Grand Duchy of Baden Clockmakers School in Furtwangen, Robert Gerwig, launched a public competition to submit designs for modern clockcases, which would allow homemade products to attain a professional appearance.

Contrary to most present-day cuckoo clocks, his case features light, unstained wood and were decorated with symmetrical, flat fretwork ornaments.

But despite intensive campaigns by the Clockmakers School, sheet metal fronts decorated with oil paintings (or coloured lithographs) never became a major market segment because of the high cost and labour-intensive process,[30] hence they were only produced from the 1850s until around 1880, whether wall or mantel versions.

"[36] By 1862, Johann Baptist Beha started to enhance his richly decorated Bahnhäusle clocks with hands carved from bone and weights cast in the shape of fir cones.

[37] Even today this combination of elements is characteristic for cuckoo clocks, although the hands are usually made of wood or plastic, white celluloid was employed in the past too.

[41] The Brienzerware chalet became a popular souvenir, allowing tourists to take home an explicit reminder of a quintessential Swiss structure, though some were rather grand in scale, measuring three or more feet across.

[43] Eventually, Black Forest makers incorporated the chalet style to their production in the early 20th century, and still remains a popular choice, along with the carved ones, among buyers of this cult item.

Cases are usually made after the traditional farmhouses of different regions, such as the Black Forest, Swiss Alps, Emmental, Bavaria and Tyrol.

[40] In the English-speaking world, cuckoo clocks are sufficiently identified with Switzerland that the 1949 film The Third Man has an oft-quoted speech (and it even had antecedents) in which the villainous Harry Lime mockingly says: " (...) in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance.

In the mid-20th century, Camerer, Cuss & Co., London, a retailer of Black Forest clocks, etc., produced a few different models in the shape of a half-timbered Tudor style house.

[49] According to author Terence Camerer Cuss, the company hoped to produce them in large quantities, but due to the high manufacturing cost, only fifty were made between 1949 and 1951.

[65] Those early timepieces, in the Black Forest style, were marketed under the trademark Poppo by Tezuka Clock Co., Ltd., Tokyo, and usually had stamped "Made in Occupied Japan" on plate and dial.

There are a wide variety of models, many of them avant-garde creations made of different materials and geometric shapes, such as rhombuses, squares, cubes, circles, rectangles, etc.