Cultural depictions of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian's reputation in historiography is many-sided, often contradictory: the last knight or the first modern foot soldier and "first cannoneer of his nation";[1][2] the first Renaissance prince (understood either as a Machiavellian politician[3] or omnicompetent, universal genius[4]) or a dilettante;[5] a far-sighted state builder and reformer, or an unrealistic schemer whose posthumous successes were based on luck,[6] or a clear-headed, prudent statesman.

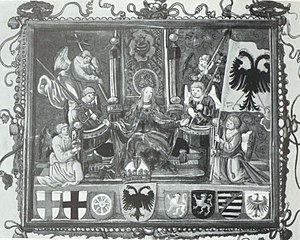

They half-captured and half-invented a rich past, which progressed from ancient Rome through the line of Charlemagne to the glory of the house of Habsburg and culminated in Maximilian's own high presidency of the Christian brotherhood of warrior-kings.

Later, after the transformation had been completed, the alchemist disappeared, leaving a gold cake of ten measures and a message: O keyser Maximilian, Wellicher dise kunst kan, Sicht dich nochs römisch reich nit an, Daß es dir solt zu gnaden gahn.

[47][48][49] The scene is depicted by Johannes Riepenhausen in his Herzog Erich der Ältere von Calenberg und Kaiser Maximilian vor der Veste Kufstein in Tirol (pen-and-ink drawing around 1836; the same artist recaptured the scene in an oil painting in 1837 with Herzog Erich von Braunschweig bittet unter eigener Gefahr den Kaiser Max um Gnade für die zu Kuffstein Verurteilten),[68] On the wall of the nearby Auracher Löchl (the oldest winehouse of Austria), there is a depiction of the "last knight" with his cannon, opposing Hans Pienzenau.

[65][69] Maximilian was a major patron of the Renaissance in the North as well as a creative force in his own right,[70][71][a][b] and as such admired and able to maintain a relationship with many important artists and scholars of his time, most notably the humanists who praised him as a second Apollo and Father of the Muses.

"[78] For Theuerdank, Freydal and Weisskunig as well as his Latin autobiography, Maximilian dictated content of chapters, provided sketches, revised drafts and was generally the driving force of these projects himself, although dozens of artists were involved in the creative process.

[74][92] The genealogical projects and the invented histories that went with them tended to attract criticisms even from the contemporaries for being overboard (even though other rulers also made extraordinary claims about their families), including the famous mathematician and astronomer Johannes Stabius.

After the origins of the Habsburg had been traced back to Noah, Kunz von der Rosen brought before the emperor a retired soldiers' harlot and a beggar, who petitioned him to support them because they were all descendants of Adam.

The function of the emperor as the promoter of arts and learning (Musagetes or Musarum pater) was important but the political mission was highlighted as well (as shown by Willibald Pirckheimer's text that accompanied the Great Triumphal Carriage, mentioned above.)

Since thy Majesty is sacred throughout the vast world Maximilian Caesar, in the furthest lands, Where Phoebus Apollo raises his golden head from eastern waves And seeks the straits called by Hercules' name, Where midday glows under his burning rays, Where the Great Bear freezes the surface of Ocean ...

The motet's text by George Slatkonia, expanding on the antiphon, reads: "The most prudent Virgin, who brought holy joys to the world, and transcended all spheres, and melted the stars beneath her feet with brilliant beams and gleaming light [...] the Mother of the eternal almighty, the Queen, powerful in Heaven, on land and at sea, whose divinity is deservingly venerated [and whom] every spirit and human being adores?

We call upon you, Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, to pour upon her ears chaste vows and prayers for the holy Empire, for the Emperor Maximilian; may the omnipotent Virgin grant that he conquer his malicious enemies; may he restore peace to the people and safety to the lands.

[209] Silver notes that Maximilian's vision of religious music was not the simple result of sacral precedents seen by him in the chapels of the Low Countries, but tied to his militancy, his self-image as a martial ruler and the strong right arm of the Christian faith.

In the case of the bard now in Vienna, the crupper plates that encase the horse's flanks form imperial double eagles that are enlivened by etched feathers and emblazoned with an escutcheon bearing the arms of Austria.

Indeed, this type of armor became associated with Maximilian, who continued to commission bards that covered horses’ legs and bellies to arm his own steeds and also as diplomatic gifts to forge alliances and demonstrate Habsburg power."

[251][252] Maximilian's relationship with notable artists and scholars of his time was a popular topic in the nineteenth century, with artworks including: The Burgundian episode and the marriage with Mary of Burgundy have a cultural afterlife.

In his lifetime, the emperor planned to build an equestrian statue of himself (based on a 1509 design by Hans Burgkmair, which itself was a revised edition of the 1508 woodcut mentioned above), which would be housed in the Church of Saints Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg.

[453] Serious academic research began in the nineteenth century with Heinrich Ulmann's two-volume work Kaiser Maximilian I., which criticized the emperor's focus on dynastic interests and failure to cooperate with the Estates on the Imperial reform in a constructive manner.

[453][454] Leopold von Ranke and his school, who did huge damage to the reputation of the emperor, also criticized Maximilian's lack of attention to imperial affairs, which in their view hampered the unification process of the German nation.

He is seen as an essentially modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial price weighed hard on the Austrians and his military expansion caused the deaths and sufferings of tens of thousands of people.

[460][461][462] Heinig comments that recent research, particularly Seyboth's work, convincingly show that the emperor's role in the operation of the political system should be rated much higher than before, or in the other words, "conceptual, communicative and organizational resources derived from the Habsburgs" are shown to be of paramount importance, and that the death of Frederick III (who was completely inaccessible regarding reform attempts) in 1493 was "the real turning point in imperial history".

Wiesflecker sees the Burgundian model's influence as predominant, Jean-Marie Cauchies und Manfred Hollegger emphasize the role of authochthonous institutions and procedures, while Wim Blockmans and Nicolette Mout note the new communication techniques imported from Italy (with the combo of patronage, book printing and propaganda).

[467] After World War II, when historians began to focus on political protests, the debate on the regency was revived with Robert Wellens's 1965 work, the first comprehensive study on the Bruges revolt of 1488 as well as Wim Blockmans's 1974 article.

[476][480][481] Holleger and Štih comment that the autocratic style, together with his visionary appetite, gave him troubles not only in Burgundian lands, but in Austria and the Holy Roman Empire also, yet reality and the will of his subjects often managed to restrain the ruler and forged his visions into more well-considered strategies.

[486][487] Regarding his diplomacy, while there was an unforeseeable factor concerning the marriages he arranged, recent scholarship also takes note of the diplomatic web (consisting of around 300 individuals, mostly from lower nobility and the bourgeoisie) he built and deployed all over Europe.

Moreover, the Burgundian government and above all its ruler, namely Philip at first and then Margaret especially, functioned as the contact center or head (Meldekopf) of the whole Habsburg Western policy, as Maximilian ran an itinerant court and thus was in no position to manage it personally.

[500] Reviewing the latter, Joachim Whaley links Maximilian's political success to activities in these fields:[500] Increasingly he is now viewed as an enterprising, visionary ruler who constructed an extraordinary imperial position out of his diverse inheritance and laid the foundations for the role the Habsburgs' played in Europe into the twentieth century.

[502][503][504] Notable experts in individual fields include: Historian Thomas A.Brady Jr. writes:[510] King Maximilian I (1459—1519) enjoys perhaps the most unsettled reputation of any figure in German history between the High Middle Ages and the Thirty Years' War.

He continues to be presented as 'the last knight' and as 'a convinced reformer' of the Empire; as the renovator of the universal ideal of Christendom and as the founder of the early modern House of Austria; and as a far-sighted builder of states and as an archaic dreamer of hopeless dreams.

[512] Historian Reinhard Seyboth notes that it is hard for biographers to meet many challenges in dealing with Maximilian, the great Habsburg ruler "who combined the characteristics of the old and new ages like no other", not only because of his extravagant multifacetedness, but also because of the complexities of his era.