Ancient Macedonians

This consolidation of territory allowed for the exploits of Alexander the Great (r. 336 – 323 BC), the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire, the establishment of the diadochi successor states, and the inauguration of the Hellenistic period in West Asia, Greece, and the broader Mediterranean world.

As a frontier kingdom on the border of the Greek world with barbarian Europe, the Macedonians first subjugated their immediate northern neighbours — various Paeonian, Illyrian and Thracian tribes — before turning against the states of southern and central Greece.

[26][27][28][29] Following the death of Alexander the Great and the Partition of Babylon in 323 BC, the diadochi successor states such as the Attalid, Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires were established, ushering in the Hellenistic period of Greece, West Asia and the Hellenized Mediterranean Basin.

[61][71] Hammond supports the traditional view that the Temenidae did arrive from the Peloponnese and took charge of Macedonian leadership, possibly usurping rule from a native "Argead" dynasty with Illyrian help.

For example, Miltiades Hatzopoulos takes Appian's testimony to mean that the royal lineage imposed itself onto the tribes of the Middle Heliacmon from Argos Orestikon,[52] whilst Eugene N. Borza argues that the Argeads were a family of notables hailing from Vergina.

[76] Thucydides describes the Macedonian expansion specifically as a process of conquest led by the Argeads:[77] But the country along the sea which is now called Macedonia, was first acquired and made a kingdom by Alexander [I], father of Perdiccas [II] and his forefathers, who were originally Temenidae from Argos.

[84] According to these scholars, direct literary, archaeological, and linguistic evidence to support Hammond's contention that a distinct Macedonian ethnos had existed in the Haliacmon valley since the Aegean civilizations is lacking.

[89] The process of state formation in Macedonia was similar to that of its neighbours in Epirus, Illyria, Thrace and Thessaly, whereby regional elites could mobilize disparate communities for the purpose of organizing land and resources.

[84] A common geography, mode of existence, and defensive interests might have necessitated the creation of a political confederacy among otherwise ethno-linguistically diverse communities, which led to the consolidation of a new Macedonian ethnic identity.

[84][91] The traditional view that Macedonia was populated by rural ethnic groups in constant conflict is slowly changing, bridging the cultural gap between southern Epirus and the north Aegean region.

[101] In addition, influences from Achaemenid Persia in culture and economy are evident from the 5th century BC onward, such as the inclusion of Persian grave goods at Macedonian burial sites as well as the adoption of royal customs such as a Persian-style throne during the reign of Philip II.

Young Macedonian men were typically expected to engage in hunting and martial combat as a byproduct of their transhumance lifestyles of herding livestock such as goats and sheep, while horse breeding and raising cattle were other common pursuits.

[105] By contrast, the alluvial plains of Lower Macedonia and Pelagonia, which had a comparative abundance of natural resources such as timber and minerals, favored the development of a native aristocracy, with a wealth that at times surpassed the classical Greek poleis.

[111] The conversion of these raw materials into finished products and their sale encouraged the growth of urban centers and a gradual shift away from the traditional rustic Macedonian lifestyle during the course of the 5th century BC.

[113] It was in the more bureaucratic regimes of the Hellenistic kingdoms succeeding Alexander the Great's empire where greater social mobility for members of society seeking to join the aristocracy could be found, especially in Ptolemaic Egypt.

One viewpoint sees it as an autocracy, whereby the king held absolute power and was at the head of both government and society, wielding arguably unlimited authority to handle affairs of state and public policy.

[119] During the Late Bronze Age (circa 15th-century BC), the ancient Macedonians developed distinct, matt-painted wares that evolved from Middle Helladic pottery traditions originating in central and southern Greece.

[101] From the sixth century, Macedonian burials became particularly lavish, displaying a rich variety of Greek imports reflecting the incorporation of Macedonia into a wider economic and political network centred on the Aegean city-states.

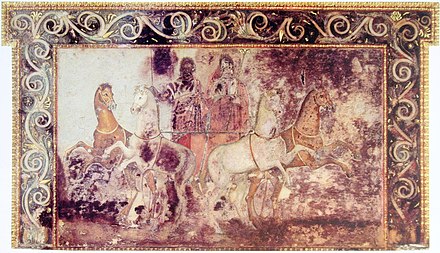

[163] Mosaics with mythological themes include scenes of Dionysus riding a panther and Helen of Troy being abducted by Theseus, the latter of which employs illusionist qualities and realistic shading similar to Macedonian paintings.

[164] Philip II was assassinated by his bodyguard Pausanias of Orestis in 336 BC at the theatre of Aigai, Macedonia amid games and spectacles held inside that celebrated the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra of Macedon.

[171] Yet Archelaus I of Macedon received a far greater number of Greek scholars, artists, and celebrities at his court than his predecessors, leading M. B. Hatzopoulos to describe Macedonia under his reign as an "active centre of Hellenic culture.

[182] Ancient Macedonia produced very few fine foods or beverages that were highly appreciated elsewhere in the Greek world, namely eels from the Strymonian Gulf and special wine brewed in Chalcidice.

[184] As exemplified by works such as the plays by the comedic playwright Menander, Macedonian dining habits penetrated Athenian high society; for instance, the introduction of meats into the dessert course of a meal.

An ethos of egalitarianism surrounded symposia, allowing all male elites to express ideas and concerns, although built-up rivalries and excessive drinking often led to quarrels, fighting and even murder.

[190] For administrative and political purposes, Attic Greek seems to have operated as a lingua franca among the ethno-linguistically diverse communities of Macedonia and the north Aegean region, creating a diglossic linguistic area.

[197] Classification attempts are based on a vocabulary of 150–200 words and 200 personal names assembled mainly from the 5th century lexicon of Hesychius of Alexandria and a few surviving fragmentary inscriptions, coins and occasional passages in ancient sources.

[264] In addition to belonging to tribal groups such as the Aeolians, Dorians, Achaeans, and Ionians, Anson also stresses the fact that some Greeks even distinguished their ethnic identities based on the polis (i.e. city-state) they originally came from.

[287] Amyntas' son and Phillip's older brother, Perdiccas III, served as theorodokos (Ancient Greek: θεωρόδοκος or θεαροδόκος) in the Panhellenic Games that took place in Epidaurus around 360/359 BC.

[295] Yet even those who considered Macedonia an ally, such as Isocrates, were keen to stress the differences between their kingdom and the Greek city states, to assuage fears about the extension of the Macedonian-style monarchism into the governance of their poleis.

"[330] Anson argues that some Hellenic authors expressed complex if not ever-changing and ambiguous ideas about the exact ethnic identity of the Macedonians, who were considered by some as barbarians, and by others as semi-Greek or fully Greek.