Expansion of Macedonia under Philip II

[7] Outside the brief notices of Philip's exploits which occur in Diodorus and Justin, further details of his campaigns (and indeed the period in general) can be found in the orations of Athenian statesmen, primarily Demosthenes and Aeschines, which have survived intact.

[28] On the other hand, Lynkestis was ruled by a competing dynasty related the Macedonian throne (and probably to Philip's mother, Eurydice) and other Upper Macedonia districts had links to foreign powers.

[31] He says that: When the armies approached each other and with a great outcry clashed in the battle, Philip, commanding the right wing, which consisted of the flower of the Macedonians serving under him, ordered his cavalry to ride past the ranks of the barbarians and attack them on the flank, while he himself falling on the enemy in a frontal assault began a bitter combat.

[49] Philip began besieging Amphipolis in 357 BC; the Amphipolitans, abandoning their anti-Athenian policy, promptly appealed to Athens, offering to return to its control.

[32] The victory against Grabos took place at the same time of the birth of Philip’s heir, Alexander, son of Myrtale (who changed her name to Olympias), which may also cemented the alliance with Epirus in the southwest.

[73] Buckler suggests that this lenient settlement may have been the result of the Thessalian request to intervene in the Third Sacred War (see below); anxious not to miss this opportunity, Philip sought to end the siege as quickly as possible.

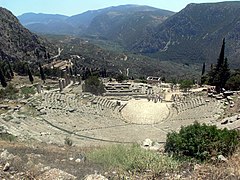

[74][75] The war was ostensibly caused by the refusal of the Phocian Confederation to pay a fine imposed on them in 357 BC by the Amphictyonic League, a pan-Greek religious organisation which governed the most sacred site in Ancient Greece, the Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

[69] Buckler, the only historian to produce a systematic study of the sacred war, therefore places Neon in 355 BC, and suggests after the meeting with Pammenes, Philip went to begin the siege of Methone.

[87] Under the terms of their alliance, Lycophron of Pherae requested aid from the Phocians, and Onomarchus dispatched his brother, Phayllos with 7000 men;[57] however, Philip repulsed this force before it could join up with the Pheraeans.

[110] The pass was narrow enough to make troop numbers irrelevant, and could only be bypassed with some difficulty, meaning the Athenians could hope to resist Philip there; Thermopylae therefore became the key position in the conflict.

[111] From Philip's point of view, once he controlled Amphipolis, he could operate in the North Aegean unimpeded, especially if he campaigned during the Etesian winds, or in winter, when the Athenian navy could do little to stop him.

[58][70] Others suggest that, in a campaign whose details are essentially unknown, Philip defeated the central Thracian king, Amadokos, reducing him to the status of subject ally.

[58] As discussed, the Chalkidian League had made peace with Athens in 352 BC, in clear breach of their alliance with Philip, due to their growing fear of Macedonian power.

[117] Philip finally began his campaign against the Chalkidian league in 349 BC, probably in July, when the Etesian winds would prevent Athens sending aid.

[124] In the end, the Athenians decided to send a force of 2000 lightly armed mercenaries (referred to in the sources as peltasts, even if strictly speaking, they were not), and 38 triremes to aid the Olynthians.

[122][126] A pre-eminent politician from Chalcis, Callias, sought to unite the cities of Euboea in a new confederation, inevitably meaning the end of the hitherto strong Athenian presence on the island.

[131] However, between the Phocians' appeal and the end of the month, all plans were upset by the return of Phalaikos to power in Phocis; the Athenians and the Spartans were subsequently told that they would not be permitted to defend Thermopylae.

[151] Philip then went on campaign against the Illyrians, particularly Pleuratus, whose Taulantii kingdom probably lay along the Drin river in modern Albania[151] and was the main independent power in Illyria after Grabus' defeat.

[32] King Glaucias and his Taulantii were probably expelled from the border area of Dassaretia,[154] but after the harsh battle against Philip they remained independent in the Adriatic coast.

[156] Philip certainly campaigned against the Epirote Cassopaeans in early 342 BC, taking control of three coastal cities (Pandosia, Elateia and Bucheta) to secure the southern regions of his kingdom.

[170] Finally, in the Fourth Philippic delivered later in 341 BC, Demosthenes argued that Athens should send an embassy to the Persian king, requesting money for a forthcoming war with Macedon.

[172] Philip's engineers constructed siege towers (some allegedly 80 cubits high), battering rams and mines for the assault, and in a short time, a section of the wall was breached.

Aid, both material and military, now began arriving at Perinthos; the Persian king ordered his satraps on the coast of Asia Minor to send money, food and weapons to the city, while the Byzantians sent a body of soldiers and their best generals.

[173] In Athens, Demosthenes proposed that the Athenians should respond by declaring war on Philip; the motion was passed, and the stone tablet recording the peace of Philocrates destroyed.

[175] The walls of Byzantion were very tall and strong, and the city was full of defenders, and well supplied by sea; it is therefore possible Philip gave up on the siege, rather than waste time and men trying to assault it.

[188] In mid-337 BC, he seems to have camped near Corinth, and began the work to establish a league of the Greek city-states, which would guarantee peace in Greece, and provide Philip with military assistance against Persia.

[204] With Macedon's vassals and allies once again peaceable, Alexander was finally free to take control of the stalled war with Persia, and in early 334 BC he crossed with an army of 42,000 men into Asia Minor.

The Macedonian army campaigned in Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia and Persia, winning notable battles at the Granicus, the Issus and Gaugamela, before the final collapse of Darius's rule in 330 BC.

The victory over Bardylis made him an attractive ally to the Epirotes, who too had suffered at the Illyrians' hands ..."[39] ^ b: Although Pausanias, the 2nd century AD geographer, claimed that Sparta was expelled from the Amphictyonic council for her part in the Sacred War, inscriptions at Delphi show that this was not the case.

[206] ^ d: For a critical review of scholars defending one view or the others, A. J. Graham provides a recapitulation during the analysis of Thasos and Portus in Colony and Mother City in Ancient Greece, explaining both Rubensohn thesis, Pouilloux objections and the indirect support for each one.