Culture of Malta

They grew cereals and raised domestic livestock and, in keeping with many other ancient Mediterranean cultures, formed a fertility cult represented in Malta by statuettes of unusually large proportions.

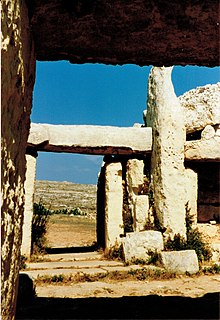

These people were either supplanted by, or gave rise to a culture of megalithic temple builders, whose surviving monuments on Malta and Gozo are considered the oldest standing stone structures in the world.

A genetic study carried out by geneticists Spencer Wells and Pierre Zalloua of the American University of Beirut argued that more than 50% of Y-chromosomes from Maltese men may have Phoenician origins.

[13] This period coincided with the golden age of Moorish culture and included innovations like the introduction of crop rotation and irrigation systems in Malta and Sicily, and the cultivation of citrus fruits and mulberries.

A proposed theory that the islands were sparsely populated during Fatimid rule is based on a citation in the French translation of the Rawd al-mi'ṭār fī khabar al-aqṭār ("The Scented Garden of Information about Places").

According to local legend,[18] the earliest Jewish residents arrived in Malta some 3,500 years ago, when the seafaring tribes of Zebulon and Asher accompanied the ancient Phoenicians in their voyages across the Mediterranean.

The earliest evidence of a Jewish presence on Malta is an inscription in the inner apse of the southern temple of Ġgantija (3600–2500 BC)[19] in Xagħra, which says, in the Phoenician alphabet: "To the love of our Father Jahwe".

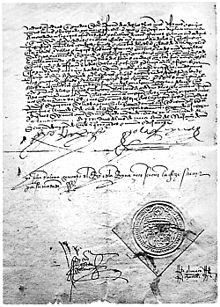

[20]In 1492, in response to the Alhambra Decree the Royal Council had argued – unsuccessfully – that the expulsion of the Jews would radically reduce the total population of the Maltese Islands, and that Malta should therefore be treated as a special case within the Spanish Empire.

Under the rule of certain Grandmasters of the Order, the Jews were made to reside in Valletta's prisons at night, while by day they remained free to transact business, trade and commerce among the general population.

Local place names around the island, such as Bir Meyru (Meyer's Well), Ġnien il-Lhud (The Jew's Garden) and Ħal Muxi (Moshé's Farm)[21] attest to the endurance of Jewish presence in Malta.

Inquisitor Federico Borromeo (iuniore) reported in 1653 that: [slaves] strolled along the street of Valletta under the pretext of selling merchandise, spreading among the women and simple-minded persons any kind of superstition, charms, love-remedies and other similar vanities.

This civic pride manifests itself in spectacular fashion during the local village festas, which mark the feast day of the patron saint of each parish with marching bands, religious processions, special Masses, fireworks (especially petards), and other festivities.

Making allowances for a possible break in the appointment of bishops to Malta during the period of the Fatimid conquest, the Maltese Church is referred to today as the only extant Apostolic See other than Rome itself.

For centuries, leadership over the Church in Malta was generally provided by the Diocese of Palermo, except under Charles of Anjou who caused Maltese bishops to be appointed, as did – on rare occasions – the Spanish and later, the Knights.

Traces of Siculo-Norman architecture can still be found in Malta's ancient capital of Mdina and in Vittoriosa, most notably in the Palaces of the Santa Sofia, Gatto Murina, Inguanez and Falzon families.

Contact between the Maltese and the many Sicilian and Italian mariners and traders who called at Valletta's busy Grand Harbour expanded under Knights, while at the same time, a significant number of Western European nobles, clerics and civil servants relocated to Malta during this period.

Maltese education, in particular, took a significant leap forward under the Knights, with the foundation, in 1592, of the Collegium Melitense, precursor to today's University of Malta, through the intercession of Pope Clement VIII.

Slavery was abolished, and the scions of Maltese nobility were ordered to burn their patents and other written evidence of their pedigrees before the arbre de la liberté that had been hastily erected in St. George's Square, at the centre of Valletta.

A popular uprising culminated with the "defenestration" of Citizen Masson, commandant of the French garrison, and the summary execution of a handful of Maltese patriots, led by Dun Mikiel Xerri.

Perhaps as an indirect result of the brutal devastation suffered by the Maltese at the hands of Benito Mussolini's Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe during World War II, the United Kingdom has replaced neighboring Italy as the dominant source of cultural influences on modern Malta.

Examples include: Alden, Atkins, Crockford, Ferry, Gingell, Hall, Hamilton, Harmsworth, Harwood, Jones, Mattocks, Moore, O'Neill, Sladden, Sixsmith, Smith, Strickland, St. John, Turner, Wallbank, Warrington, Kingswell and Woods.

More significantly, by the mid-19th century the Maltese already had a long history of migration to various places, including Egypt, Tripolitania, Tunisia, Algeria, Cyprus, the Ionian Islands, Greece, Sicily and Lampedusa.

Radio shows, television programs and the easy availability of foreign newspapers and magazines throughout the 20th century further extended and enhanced the impact of both British and Italian culture on Malta.

Clubs frequently have large outdoor patios, with local and visiting DJs spinning a mix of Euro-beat, House, chill-out, R&B, hardcore, rock, trance, techno, retro, old school, and classic disco.

Laid back wine bars are increasingly popular among young professionals and the more discriminating tourists, and are popping up in the kantinas of some of the more picturesque, historic cities and towns, including Valletta and Vittoriosa.

Despite rapidly increasing tolerance and acceptance of alternative lifestyles, Malta offers its gay and lesbian locals and visitors less nightlife options than other Southern European destinations.

[40] Between 1798 and 1800, while Malta was under the rule of Napoleonic France, a Maltese translation of L-Għanja tat-Trijonf tal-Libertà (Ode to the Triumph of Liberty), by Citizen La Coretterie, Secretary to the French Government Commissioner, was published on the occasion of Bastille Day.

They host local and foreign artistes, with a calendar of events that includes modern and period drama in both national languages, musicals, opera, operetta, dance, concerts and poetry recitals.

Towards the end of the 15th century, Maltese artists, like their counterparts in neighbouring Sicily, came under the influence of the School of Antonello da Messina, which introduced Renaissance ideals and concepts to the decorative arts in Malta.

Romanticism, tempered by the naturalism introduced to Malta by Giuseppe Calì, informed the "salon" artists of the early 20th century, including Edward and Robert Caruana Dingli.