Culture of the Ming dynasty

The culture of the Ming dynasty was deeply rooted in traditional Chinese values, but also saw a flourishing of fine arts, literature, and philosophy in the late 15th century.

During this time, the government played a stronger role in shaping culture, requiring the use of Zhu Xi's interpretation of Neo-Confucianism in civil service examinations and promoting "proper" art in literature and painting.

He based his conceptual script on the style of the Northern Song calligrapher Huang Tingjian, using plump and rounded strokes that were written with a sense of haste.

[3] Another influential figure in the calligraphy world at the time was Wu Kuan (吳寬), Minister of Rites, who followed the style of another Northern Song artist, Su Shi.

In the first half of the 17th century, Chen Hongshou, a calligrapher and professional painter specializing in figure painting, gained recognition for his unique expression, which continued to be admired in the years to come.

Despite the seemingly chaotic appearance of his writing, Wang Duo's personal and inventive style aligns with Dong Qichang's belief that calligraphy should not simply copy, but rather creatively transform the patterns of the past.

[20] They drew inspiration from the works of Ma Yuan (active c. 1190–1264), Xia Gui (first half of the 13th century), which were collectively known as the "Ma–Xia style", as well as Guo Xi (c. 1020–1070) and green-blue landscapes.

[20] Dong emphasized the idea of painting as a form of calligraphy and promoted the creation of a "grand synthesis" (da cheng) of artistic style through the study of past masters.

[3] He positioned himself as the culmination of the southern school's development, as the true heir of literary painting that strives to express the ideas of the creator rather than seeking material gain.

As a poet, he was versatile, composing yuefu ballads, sao (騷) style poems, shi poetry, ci songs, and qu arias.

[33] The purges carried out by the Ming founder Hongwu Emperor resulted in the deaths of many literati, and the government's strict control over literary production may have contributed to the lack of great poets during the 15th century.

[36] Among the scholars during the Hongwu Emperor's reign, Liu Ji gained the most recognition for his contemplative poems, while Song Lian was primarily known as a prose-writer.

With the economic rise of Jiangnan at the end of the 15th century, it also gave birth to a constellation of scholars, some of whom even reached high positions in the government, such as Wu Kuan and Wang Ao.

The art of Suzhou continued to flourish in the next generation with artists like Yang Xunji (楊循吉), Zhu Yunming, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming.

During the reign of the Hongzhi Emperor (1487–1505), the favorable political climate allowed them to take their roles as officials, poets, and philosophers more seriously and refine their views through discussions at their meetings in the capital.

[41] The trend of returning to traditional poetic styles began before the middle of the 16th century, led by Xie Zhen, a southerner who had failed in his career and embraced the individualistic ideas of He Jingming.

Other notable poets in this movement, known as the "Latter Seven Masters of the Ming", included Li Panlong (李攀龍), Wang Shizhen (王世貞), Xu Zhongxing, Liang Youyu, Zong Chen, and Wu Guolun (吳國倫).

This is evident in the works of authors such as Song Lian, Liu Ji, Yang Shiqi, and many other officials and scholars who are classified as "followers of old literature" (guwen pai).

The Ming period is best known for its extensive collection of multi-volume encyclopedic works and anthologies,[46] both state-owned (such as the Yongle Encyclopedia) and private (such as the Compendium of Materia Medica from the late 16th century).

[59] In hopes of achieving commercial success, Ming publishers also released handbooks on a variety of topics, ranging from funeral customs to multiplication tables to contract templates and dream dictionaries.

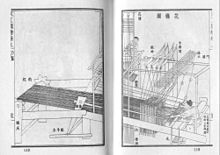

[61] Ming publishers were pioneers in book production, and in the first half of the 17th century, Wu Faxiang introduced blind printing to create a plastic effect.

This trend was further reinforced by government regulations, such as the 1373 ban on actors portraying monarchs, their concubines, loyal courtiers, and noble patriots and sages from all dynasties, except for those who were considered models of proper behavior.

[75] The popularity of zaju declined after Zhu Youdun, but it was revived in the early 16th century by Kang Hai and Wang Jiusi, who were inspired by their love for the genre.

[77] Shen Jing (沈璟; 1553–1610) formulated the rules of composition, emphasizing the harmony of melodies, and his students formed the renowned Wujiang school.

The court's high standards for quality led to an increase in the level of private porcelain factories, allowing them to cater to the demands of wealthy and discerning customers.

[82] During the late Ming period, private workshops emerged as the main hubs of creativity and production, replacing state-run porcelain factories.

[3] By the early 17th century, certain masters in the field of porcelain-making gained recognition for their exceptional skills, such as He Chaozong, renowned for his exquisite white porcelain figurines.

Examples of this style can be seen in the construction of the Forbidden City, the Temple of Confucius in Qufu, and the buildings on the sacred Buddhist mountain of Wutaishan in Shaanxi province.

[91] While there are still many preserved Buddhist statues and sculptures made of bronze, wood, and lacquer, they lack the expressive power seen in Tang and Song works.

Architects distinguished between northern and southern styles of gardens and parks; the former was characterized by large dimensions and vibrant colors, while the latter was known for its modesty and monochromatic design.