Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining

[1] Similar to the French phrase bon appétit or the act of saying grace, itadakimasu serves as an expression of gratitude for all who played a role in providing the food, including farmers, as well as the living organisms that gave their life to become part of the meal.

[9] Not finishing one's meal is not considered impolite in Japan, but rather is taken as a signal to the host that one wishes to be served another helping.

Rice is generally eaten plain or sometimes with nori (very thin sheets of dried seaweed, perhaps shredded or cut into strips) or furikake (a seasoning).

More substantial additives may also be provided: a raw egg, nattō (sticky fermented soy beans), a small piece of cooked fish, or tsukemono (preserved vegetables).

At each diner's seat, a small dish is provided for holding the sauce and dipping in a bit of food.

To pour an excessive amount of soy sauce into this dish is considered greedy and wasteful (see mottainai).

Leaving stray grains of rice floating in the sauce is considered uncouth, but can be hard to avoid for those who have difficulty manipulating chopsticks.

It is uncommon for Japanese people to eat or drink while walking in public because it can be seen as inconsiderate to others.

Many Japanese restaurants provide diners with single-use wooden/bamboo chopsticks that must be snapped apart near their tops (which are thicker than the bottoms).

Never rub chopsticks against each other to remove splinters: this is considered extremely rude, implying that one thinks the utensils are cheap.

At the beginning of the meal, use the smooth bottom ends to pick up food from serving dishes if no other utensils have been provided for that purpose.

At the end of the meal, it is good manners to return single-use chopsticks part way into their original paper wrapper; this covers the soiled sticks while indicating that the package has been used.

It is considered rude to use the towel to wipe the face or neck; however, some people, usually men, do this at more informal restaurants.

In any situation, an uncertain diner can observe what others are doing; and for non-Japanese people to ask how to do something properly is generally received with appreciation for the acknowledgment of cultural differences and expression of interest in learning Japanese ways.

However, traditional Japanese low tables and cushions, usually found on tatami floors, are also very common.

To sit in a seiza position, one kneels on the floor with legs folded under the thighs and the buttocks resting on the heels.

[15] Before eating, most dining places provide either a hot or cold towel or a plastic-wrapped wet napkin (o-shibori).

Other important perceptions to remember include the following:[17] Chopsticks, after being picked up with one hand, should be held firmly while considering three key points: the thumb is placed just how a pencil is held; ensure that the thumb is touched with the upper part of the chopstick.

It is considered ungrateful to make these requests, especially in circumstances where one is being hosted, as in a business dinner environment or a home.

Even in informal situations, drinking alcohol starts with a toast (kanpai, 乾杯) when everyone is ready.

If a series of small foods are served, it is important to fully finish off one dish prior to moving on to the next one.

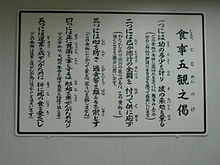

Today, Buddhism is the firm root of the vital dining etiquette that is universally practised in Japan.

[38] Itadakimasu, the phrase that is used to show gratitude for those involved in making the meal (i.e., farmers, fishermen, parents, etc.

[39] The belief from Buddhism that every object has a spirit to be recognised is implied by the phrase, manifesting both gratitude and honour to pay respect to the lives that made the food, including the cook, animals, farmers, and plants.

The appearance of rice floating around on the shoyu plate is not considered a taboo in Japanese culture, but it may leave a bad impression.

[46] Bentō, boxed meals in Japan, are very common and constitute an important ritual during lunch, beginning around the time children reach nursery school.

Parents take special care when preparing meals for their children, arranging the food in the order in which it will be eaten.

Though the food is prepared for their child, the results are observed by the other children and the nursery school, and this leads to a sort of competition among parents.

[citation needed] Because the appearance of food is important in Japan, parents must be sure to arrange the bentō in an attractive way.

[47] A parent may prepare a leaf cut-out in fall, or cut an orange into the shape of a flower if the season is summer.