Cyclic group

n or Zn, not to be confused with the commutative ring of p-adic numbers), that is generated by a single element.

For any element g in any group G, one can form the subgroup that consists of all its integer powers: ⟨g⟩ = { gk | k ∈ Z }, called the cyclic subgroup generated by g. The order of g is |⟨g⟩|, the number of elements in ⟨g⟩, conventionally abbreviated as |g|, as ord(g), or as o(g).

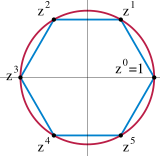

Under a change of letters, this is isomorphic to (structurally the same as) the standard cyclic group of order 6, defined as C6 = ⟨g⟩ = { e, g, g2, g3, g4, g5 } with multiplication gj · gk = gj+k (mod 6), so that g6 = g0 = e. These groups are also isomorphic to Z/6Z = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5} with the operation of addition modulo 6, with zk and gk corresponding to k. For example, 1 + 2 ≡ 3 (mod 6) corresponds to z1 · z2 = z3, and 2 + 5 ≡ 1 (mod 6) corresponds to z2 · z5 = z7 = z1, and so on.

Any element generates its own cyclic subgroup, such as ⟨z2⟩ = { e, z2, z4 } of order 3, isomorphic to C3 and Z/3Z; and ⟨z5⟩ = { e, z5, z10 = z4, z15 = z3, z20 = z2, z25 = z } = G, so that z5 has order 6 and is an alternative generator of G. Instead of the quotient notations Z/nZ, Z/(n), or Z/n, some authors denote a finite cyclic group as Zn, but this clashes with the notation of number theory, where Zp denotes a p-adic number ring, or localization at a prime ideal.

[note 1] The set of integers Z, with the operation of addition, forms a group.

[1] It is an infinite cyclic group, because all integers can be written by repeatedly adding or subtracting the single number 1.

The addition operations on integers and modular integers, used to define the cyclic groups, are the addition operations of commutative rings, also denoted Z and Z/nZ or Z/(n).

When (Z/nZ)× is cyclic, its generators are called primitive roots modulo n. For a prime number p, the group (Z/pZ)× is always cyclic, consisting of the non-zero elements of the finite field of order p. More generally, every finite subgroup of the multiplicative group of any field is cyclic.

[6] The set of rotational symmetries of a polygon forms a finite cyclic group.

In three or higher dimensions there exist other finite symmetry groups that are cyclic, but which are not all rotations around an axis, but instead rotoreflections.

The group of rotations by rational angles is countable, but still not cyclic.

The set of all nth roots of unity forms a cyclic group of order n under multiplication.

For fields of characteristic zero, such extensions are the subject of Kummer theory, and are intimately related to solvability by radicals.

Specifically, all subgroups of Z are of the form ⟨m⟩ = mZ, with m a positive integer.

[10] Thus, since a prime number p has no nontrivial divisors, pZ is a maximal proper subgroup, and the quotient group Z/pZ is simple; in fact, a cyclic group is simple if and only if its order is prime.

For every positive divisor d of n, the quotient group Z/nZ has precisely one subgroup of order d, generated by the residue class of n/d.

For a finite cyclic group of order n, gn is the identity element for any element g. This again follows by using the isomorphism to modular addition, since kn ≡ 0 (mod n) for every integer k. (This is also true for a general group of order n, due to Lagrange's theorem.)

Because a cyclic group is abelian, each of its conjugacy classes consists of a single element.

If n and m are coprime, then the direct product of two cyclic groups Z/nZ and Z/mZ is isomorphic to the cyclic group Z/nmZ, and the converse also holds: this is one form of the Chinese remainder theorem.

[13] The sequence of cyclic numbers include all primes, but some are composite such as 15.

In the complex case, a representation of a cyclic group decomposes into a direct sum of linear characters, making the connection between character theory and representation theory transparent.

In the positive characteristic case, the indecomposable representations of the cyclic group form a model and inductive basis for the representation theory of groups with cyclic Sylow subgroups and more generally the representation theory of blocks of cyclic defect.

A trivial path (identity) can be drawn as a loop but is usually suppressed.

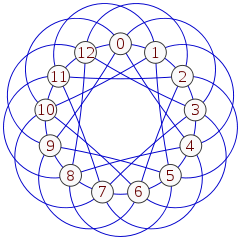

[15] A cyclic group Zn, with order n, corresponds to a single cycle graphed simply as an n-sided polygon with the elements at the vertices.

[18] Under this isomorphism, the number r corresponds to the endomorphism of Z/nZ that maps each element to the sum of r copies of it.

For the Hom group, recall that it is isomorphic to the subgroup of Z / nZ consisting of the elements of order dividing m. That subgroup is cyclic of order gcd(m, n), which completes the proof.

An infinite group is virtually cyclic if and only if it is finitely generated and has exactly two ends;[note 3] an example of such a group is the direct product of Z/nZ and Z, in which the factor Z has finite index n. Every abelian subgroup of a Gromov hyperbolic group is virtually cyclic.

[20] A profinite group is called procyclic if it can be topologically generated by a single element.

An example is the additive group of the rational numbers: every finite set of rational numbers is a set of integer multiples of a single unit fraction, the inverse of their lowest common denominator, and generates as a subgroup a cyclic group of integer multiples of this unit fraction.

A group is polycyclic if it has a finite descending sequence of subgroups, each of which is normal in the previous subgroup with a cyclic quotient, ending in the trivial group.