Cyclic order

In mathematics, a cyclic order is a way to arrange a set of objects in a circle.

[nb] Some familiar cycles are discrete, having only a finite number of elements: there are seven days of the week, four cardinal directions, twelve notes in the chromatic scale, and three plays in rock-paper-scissors.

There are also cyclic orders with infinitely many elements, such as the oriented unit circle in the plane.

Alternatively, a cycle with n elements is also a Zn-torsor: a set with a free transitive action by a finite cyclic group.

It can be instinctive to use cyclic orders for symmetric functions, for example as in where writing the final monomial as xz would distract from the pattern.

A substantial use of cyclic orders is in the determination of the conjugacy classes of free groups.

Two elements g and h of the free group F on a set Y are conjugate if and only if, when they are written as products of elements y and y−1 with y in Y, and then those products are put in cyclic order, the cyclic orders are equivalent under the rewriting rules that allow one to remove or add adjacent y and y−1.

Important examples of infinite cycles include the unit circle, S1, and the rational numbers, Q.

Instead, we use a ternary relation denoting that elements a, b, c occur after each other (not necessarily immediately) as we go around the circle.

The automorphisms of a cyclically ordered set may be identified with C2, the two-element group, of direct and opposite correspondences.

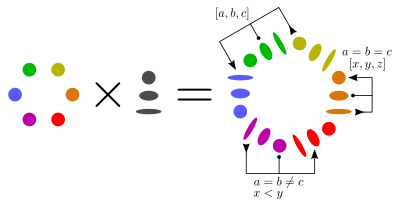

Generally, an injective function f from an unordered set X to a cycle Y induces a unique cyclic order on X that makes f an embedding.

A cyclic order on a finite set X can be determined by an injection into the unit circle, X → S1.

In order to quantify this redundancy, it takes a more complex combinatorial object than a simple number.

Examining the configuration space of all such maps leads to the definition of an (n − 1)-dimensional polytope known as a cyclohedron.

For example, given two linearly ordered sets L1 and L2, one may form a circle by joining them together at positive and negative infinity.

The generalization to a locally partially ordered space is studied in Roll (1993); see also Directed topology.

[29] Replacing the asymmetry axiom with a complementary version results in the definition of a co-cyclic order.

One structure that weakens this axiom is a CC system: a ternary relation that is cyclic, asymmetric, and total, but generally not transitive.

[31] Evans, Macpherson & Ivanov (1997) provide a model-theoretic description of the covering maps of cycles.

Giraudet & Holland (2002) characterize cycles whose full automorphism groups act freely and transitively.

Campero-Arena & Truss (2009) characterize countable colored cycles whose automorphism groups act transitively.

Truss (2009) studies the automorphism group of the unique (up to isomorphism) countable dense cycle.

Some experiments have been performed to investigate the mental representations of cyclically ordered sets, such as the months of the year.

Finally, some authors may take cyclic order to mean an unoriented quaternary separation relation (Bowditch 1998, p. 155).

^cycle A set with a cyclic order may be called a cycle (Novák 1982, p. 462) or a circle (Giraudet & Holland 2002, p. 1).

The literature on groups, such as Świerczkowski (1959a, p. 162) and Černák & Jakubík (1987, p. 157), tend to use square brackets: [a, b, c].

Giraudet & Holland (2002, p. 1) use round parentheses: (a, b, c), reserving square brackets for a betweenness relation.

Some authors use infix notation: a < b < c, with the understanding that this does not carry the usual meaning of a < b and b < c for some binary relation < (Černy 1978, p. 262).

^orbit space The map T is called archimedean by Bowditch (2004, p. 33), coterminal by Campero-Arena & Truss (2009, p. 582), and a translation by McMullen (2009, p. 10).

Freudenthal & Bauer (1974, p. 10) call Z × K the "∞-times covering" of K. Often this construction is written as the anti-lexicographic order on K × Z.