Population genetics

Traditionally a highly mathematical discipline, modern population genetics encompasses theoretical, laboratory, and field work.

But with blending inheritance, genetic variance would be rapidly lost, making evolution by natural or sexual selection implausible.

According to this principle, the frequencies of alleles (variations in a gene) will remain constant in the absence of selection, mutation, migration and genetic drift.

In a series of papers starting in 1918 and culminating in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, Fisher showed that the continuous variation measured by the biometricians could be produced by the combined action of many discrete genes, and that natural selection could change allele frequencies in a population, resulting in evolution.

B. S. Haldane, worked out the mathematics of allele frequency change at a single gene locus under a broad range of conditions.

Haldane also applied statistical analysis to real-world examples of natural selection, such as peppered moth evolution and industrial melanism, and showed that selection coefficients could be larger than Fisher assumed, leading to more rapid adaptive evolution as a camouflage strategy following increased pollution.

[4][5] The American biologist Sewall Wright, who had a background in animal breeding experiments, focused on combinations of interacting genes, and the effects of inbreeding on small, relatively isolated populations that exhibited genetic drift.

[citation needed] The work of Fisher, Haldane and Wright founded the discipline of population genetics.

This integrated natural selection with Mendelian genetics, which was the critical first step in developing a unified theory of how evolution worked.

[4][5] John Maynard Smith was Haldane's pupil, whilst W. D. Hamilton was influenced by the writings of Fisher.

[citation needed] The mathematics of population genetics were originally developed as the beginning of the modern synthesis.

For the first few decades of the 20th century, most field naturalists continued to believe that Lamarckism and orthogenesis provided the best explanation for the complexity they observed in the living world.

[7] During the modern synthesis, these ideas were purged, and only evolutionary causes that could be expressed in the mathematical framework of population genetics were retained.

[8] Theodosius Dobzhansky, a postdoctoral worker in T. H. Morgan's lab, had been influenced by the work on genetic diversity by Russian geneticists such as Sergei Chetverikov.

He helped to bridge the divide between the foundations of microevolution developed by the population geneticists and the patterns of macroevolution observed by field biologists, with his 1937 book Genetics and the Origin of Species.

Many more biologists were influenced by population genetics via Dobzhansky than were able to read the highly mathematical works in the original.

Ford's work, in collaboration with Fisher, contributed to a shift in emphasis during the modern synthesis towards natural selection as the dominant force.

[13] The main processes influencing allele frequencies are natural selection, genetic drift, gene flow and recurrent mutation.

Population genetics describes natural selection by defining fitness as a propensity or probability of survival and reproduction in a particular environment.

However, the effect of deleterious mutations tends on average to be very close to multiplicative, or can even show the opposite pattern, known as "antagonistic epistasis".

This process is often characterized by a description of the starting and ending states, or the kind of change that has happened at the level of DNA (e.g,.

In deterministic theory, evolution begins with a predetermined set of alleles and proceeds by shifts in continuous frequencies, as if the population is infinite.

The shifting balance theory of Sewall Wright held that the combination of population structure and genetic drift was important.

[45] The role of genetic drift by means of sampling error in evolution has been criticized by John H Gillespie[46] and Will Provine,[47] who argue that selection on linked sites is a more important stochastic force, doing the work traditionally ascribed to genetic drift by means of sampling error.

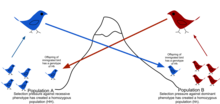

[50] Genetic structuring can be caused by migration due to historical climate change, species range expansion or current availability of habitat.

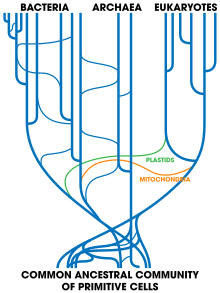

[56] Horizontal transfer of genes from bacteria to eukaryotes such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the adzuki bean beetle Callosobruchus chinensis may also have occurred.

[57][58] An example of larger-scale transfers are the eukaryotic bdelloid rotifers, which appear to have received a range of genes from bacteria, fungi, and plants.

[60] Large-scale gene transfer has also occurred between the ancestors of eukaryotic cells and prokaryotes, during the acquisition of chloroplasts and mitochondria.

[67] For example, one analysis suggests that larger populations have more selective sweeps, which remove more neutral genetic diversity.

One common approach is to look for regions of high linkage disequilibrium and low genetic variance along the chromosome, to detect recent selective sweeps.