DNA vaccine

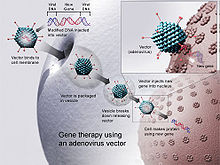

The DNA is injected into the body and taken up by cells, whose normal metabolic processes synthesize proteins based on the genetic code in the plasmid that they have taken up.

[9][10] In 1993, Jeffrey Ulmer and co-workers at Merck Research Laboratories demonstrated that direct injection of mice with plasmid DNA encoding a flu antigen protected the animals against subsequent experimental infection with influenza virus.

Separately, Inovio Pharmaceuticals and GeneOne Life Science began tests of a different DNA vaccine against Zika in Miami.

These are plasmids that usually consist of a strong viral promoter to drive the in vivo transcription and translation of the gene (or complementary DNA) of interest.

[19] Plasmids also include a strong polyadenylation/transcriptional termination signal, such as bovine growth hormone or rabbit beta-globulin polyadenylation sequences.

[6] More recently, expression and immunogenicity have been further increased in model systems by the use of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter, and a retroviral cis-acting transcriptional element.

Well-known catalysts of genetic instability include direct, inverted and tandem repeats, which are conspicuous in many commercially available cloning and expression vectors.

Therefore, the reduction or complete elimination of extraneous noncoding backbone sequences would pointedly reduce the propensity for such events to take place and consequently the overall plasmid's recombinogenic potential.

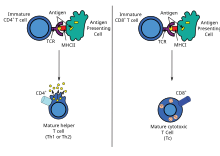

The antigen-presenting cell then travels to the lymph nodes and presents the antigen peptide and costimulatory molecule signalling to T-cell, initiating the immune response.

Injection in saline is normally conducted intramuscularly (IM) in skeletal muscle, or intradermally (ID), delivering DNA to extracellular spaces.

This can be assisted either 1) by electroporation;[32] 2) by temporarily damaging muscle fibres with myotoxins such as bupivacaine; or 3) by using hypertonic solutions of saline or sucrose.

An E. coli inner core and poly(beta-amino ester) outer coat function synergistically to increase efficiency by addressing barriers associated with antigen-presenting cell gene delivery which include cellular uptake and internalization, phagosomal escape and intracellular cargo concentration.

[48] These peptides are derived from cytosolic proteins that are degraded and delivered to the nascent MHC class I molecule within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

This was successfully demonstrated using recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing influenza proteins,[48] but the principle should also be applicable to DNA vaccines.

[50] Co-inoculation with plasmids encoding co-stimulatory molecules IL-12 and TCA3 were shown to increase CTL activity against HIV-1 and influenza nucleoprotein antigens.

[52] Antibody-secreting cells (ASC) migrate to the bone marrow and spleen for long-term antibody production, and generally localise there after one year.

[clarification needed] DNA vaccine expressing HBV small and middle envelope protein was injected into adults with chronic hepatitis.

Two theories dominate – that in vivo uptake of DNA occurs non-specifically, in a method similar to phago- or pinocytosis,[21] or through specific receptors.

[clarification needed] The 30kDa surface receptor binds specifically to 4500-bp DNA fragments (which are then internalised) and is found on professional APCs and T-cells.

[49][59] After gene gun inoculation to the skin, transfected Langerhans cells migrate to the draining lymph node to present antigens.

[7] After IM and ID injections, dendritic cells present antigen in the draining lymph node[56] and transfected macrophages have been found in the peripheral blood.

[60] Besides direct transfection of dendritic cells or macrophages, cross priming occurs following IM, ID and gene gun DNA deliveries.

Transfected Langerhans cells migrate out of the skin (within 12 hours) to the draining lymph node where they prime secondary B- and T-cell responses.

Instead, IM inoculated DNA "washes" into the draining lymph node within minutes, where distal dendritic cells are transfected and then initiate an immune response.

[21][54][61] DNA vaccination generates an effective immune memory via the display of antigen-antibody complexes on follicular dendritic cells (FDC), which are potent B-cell stimulators.

[6][7] Bacterially derived DNA can trigger innate immune defence mechanisms, the activation of dendritic cells and the production of TH1 cytokines.

In contrast, nucleotide sequences that inhibit the activation of an immune response (termed CpG neutralising, or CpG-N) are over represented in eukaryotic genomes.

CpG-S sequences have also been used as external adjuvants for both DNA and recombinant protein vaccination with variable success rates.

Primed mice with plasmid DNA encoding Plasmodium yoelii circumsporozoite surface protein (PyCSP), then boosted with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the same protein had significantly higher levels of antibody, CTL activity and IFN-γ, and hence higher levels of protection, than mice immunized and boosted with plasmid DNA alone.

Partial protection against sporozoite challenge was achieved, and mean parasitemia was significantly reduced, compared to control monkeys.