Roman Dacia

His last minute decision just before the Battle of Pharsalus to participate in the Roman Republic's civil war by supporting Pompey meant that once the Pompeians were dealt with, Julius Caesar would turn his eye towards Dacia.

[1] This saw the occasional granting of favoured status to the Dacians in the manner of being identified as amicii et socii – "friends and allies" – of Rome, although by the time of Octavianus this was tied up with the personal patronage of important Roman individuals.

[9][10] Although it is believed that the custom of providing royal hostages to the Romans may have commenced sometime during the first half of the 1st century BC, it was certainly occurring by Octavianus' reign and it continued to be practised during the late pre-Roman period.

[16] In 102,[17] after a series of engagements, negotiations led to a peace settlement where Decebalus agreed to demolish his forts while allowing the presence of a Roman garrison at Sarmizegetusa Regia (Grădiștea Muncelului, Romania) to ensure Dacian compliance with the treaty.

[34] Crito wrote that approximately 500,000 Dacians were enslaved and deported, a portion of which were transported to Rome to participate in the gladiatorial games (or lusiones) as part of the celebrations to mark the emperor's triumph.

[35] Nevertheless, native Dacians remained at the periphery of the province and in rural settings, while local power elites were encouraged to support the provincial administration, a usual Roman colonial practice.

When barbarian incursions resumed during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the defences in Dacia were hard pressed to halt all of the raids, leaving exposed the provinces of Upper and Lower Moesia.

[74][75] Fighting continued in Dacia over the next two years, and by 169, the governor of the province Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, was forced to give up his command – it is suspected that he either contracted the plague or died in battle.

As a result, the Astingi committed no further acts of hostility against the Romans, but in response to urgent supplications addressed to Marcus they received from him both money and the privilege of asking for land in case they should inflict some injury upon those who were then fighting against him.Throughout this period, the tribes bordering Dacia to the east, such as the Roxolani, did not participate in the mass invasions of the empire.

[86] While this worked in the case of the Roxolani, the use of the Roman-client relationships that allowed the Romans to pit one supported tribe against another facilitated the conditions that created the larger tribal federations that emerged with the Quadi and the Marcomanni.

[93] Commodus' legates devastated a territory some 8 km (5.0 mi) deep along the north of the castrum at modern day Gilău to establish a buffer in the hope of preventing further barbarian incursions.

[122] Although Eutropius,[123] supported by minor references in the works of Cassius Dio[124] and Julian the Apostate,[125][126] describes the widespread depopulation of the province after the siege of Sarmizegetusa Regia and the suicide of king Decebalus,[52] there are issues with this interpretation.

[130] The archaeological evidence from various types of settlements, especially in the Oraștie Mountains, demonstrates the deliberate destruction of hill forts during the annexation of Dacia, but this does not rule out a continuity of occupation once the traumas of the initial conquest had passed.

[53] The Marcomannic Wars that erupted north of the Danube forced Marcus Aurelius to reverse this policy, permanently transferring the Legio V Macedonica from Troesmis (modern Turcoaia in Romania)[158] in Moesia Inferior to Potaissa in Dacia.

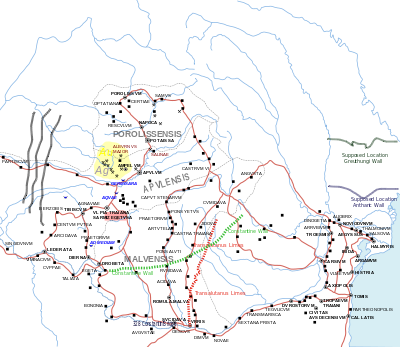

[161] Military documents report at least 58 auxiliary units, most transferred into Dacia from the flanking Moesian and Pannonian provinces, with a wide variety of forms and functions, including numeri, cohortes milliariae, quingenariae, and alae.

However, in the mid-Mureș valley, associated civilian communities have been uncovered next to the auxiliary camps at Orăștioara de Sus, Cigmău, Salinae (modern Ocna Mureș), and Micia,[183] with a small amphitheatre being discovered at the latter one.

[128] Linking into Rome's monetary economy, bronze Roman coinage was eventually produced in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa[164] by about 250 AD (previously Dacia seems to have been supplied with coins from central mints).

[191] Villages and rural settlements continued to specialise in craftwork, including pottery, and sites such as Micăsasa could possess 26 kilns and hundreds of moulds for the manufacture of local terra sigillata.

[201] This appears to be an urban feature only – the minority of cemeteries excavated in rural areas display burial sites that have been identified as Dacian, and some have been conjectured to be attached to villa settlements, such as Deva, Sălașu de Sus, and Cincis.

[208] While Gordian III eventually emerged as Roman Emperor, the confusion in the heart of the empire allowed the Goths, in alliance with the Carpi, to take Histria in 238[209] before sacking the economically important commercial centres along the Danube Delta.

[210] Unable to deal militarily with this incursion, the empire was forced to buy peace in Moesia, paying an annual tribute to the Goths; this infuriated the Carpi who also demanded a payment subsidy.

[218] Firmly entrenched in the territories along the lower Danube and the Black Sea's western shore, their presence affected both the non-Romanized Dacians (who fell into the Goth's sphere of influence)[219] and Imperial Dacia, as the client system that surrounded the province and supported its existence began to break apart.

It seems as if he had been raised to sovereign eminence, at once to rage against God, and at once to fall; for, having undertaken an expedition against the Carpi, who had then possessed themselves of Dacia and Moesia, he was suddenly surrounded by the barbarians, and slain, together with great part of his army; nor could he be honored with the rites of sepulture, but, stripped and naked, he lay to be devoured by wild beasts and birds, – a fit end for the enemy of God.Continuing pressures during the reign of the emperor Gallienus (253–268) and the fracturing of the western half of the empire between himself and Postumus in Gaul after 260 meant that Gallienus' attention was principally focused on the Danubian frontier.

[206] The latest coins at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Porolissum bear his effigy,[228] and the raising of inscribed monuments in the province virtually ceased in 260,[229] the year that marked the temporary breakup of the empire.

[262] Hoping to regain the trans-Danubian beachhead which Constantine had successfully established at Sucidava,[263] Valens launched a raid into Gothic territory after crossing the Danube near Daphne around 30 May; they continued until September without any serious engagements.

The aim was to secure the Balkan provinces and Danubian frontier against continued incursions from Slavic and Avar raids, fortifying several settlements and fortresses along the river, but this also involved some victories over these enemies deeper into their lands to the north, including Pannonia as well.

[269][270] However, despite these successes in re-establishing the frontier, in 602 a mutiny within the exhausted Byzantine army stationed north of the river in what was once Dacia (with the expectation that they would continue to stay and campaign there over the winter, despite pay cuts) caused the emperor to be overthrown by one of his generals, Phocas, culminating in the eventual collapse of Roman control of the Balkans over the coming decades as attention had to be turned east to Persian[271] and later Arab threats.

Based on the written accounts of ancient authors such as Eutropius, it had been assumed by some Enlightenment historians such as Edward Gibbon that the population of Dacia Traiana was moved south when Aurelian abandoned the province.

[276] Pottery remains dated to the years after 271 AD in Potaissa,[158] and Roman coinage of Marcus Claudius Tacitus and Crispus (son of Constantine I) uncovered in Napoca demonstrate the continued survival of these towns.

[280] Repeated archaeological investigations from the 19th century onwards have failed to uncover definitive proof that a large proportion of the Daco-Romans remained in Dacia after the evacuation;[281] for example, traffic in Roman coins in the former province after 271 show similarities to modern Slovakia and the steppe in what is today Ukraine.