Dakota War of 1862

[8] All four bands of eastern Dakota had been pressured into ceding large tracts of land to the United States in a series of treaties and were reluctantly moved to a reservation strip twenty miles wide, centered on Minnesota River.

[10] That night, a faction led by Chief Little Crow decided to attack the Lower Sioux Agency the next morning in an effort to drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley.

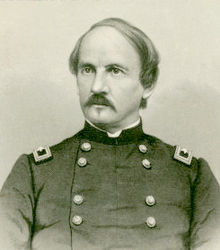

[8]: 12 The demands of the Civil War slowed the U.S. government response, but on September 23, 1862, an army of volunteer infantry, artillery and citizen militia assembled by Governor Alexander Ramsey and led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley finally defeated Little Crow at the Battle of Wood Lake.

"[23] The eastern Dakota were pressured into ceding large tracts of land to the United States in a series of treaties negotiated with the U.S. government and signed in 1837, 1851 and 1858, in exchange for cash annuities, debt payments, and other provisions.

This shortage of wild game not only made it difficult for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota to directly obtain meat, but also reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies.

[37] On August 4, 1862, representatives of the northern Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota bands met at the Upper Sioux Agency in the northwestern part of the reservation and successfully negotiated to obtain food.

it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dying with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung.

[43]: 307 According to Wingerd, up to 300 Sissetons and Wahpetons may have joined in the fighting – only a fraction out of the 4,000 who lived near the Upper Sioux Agency – in defiance of their tribal elders, who opposed participation in what they warned would be a suicidal offensive.

[25]: 6, 12 Killing was suspended for a time while the attackers turned their attention to raiding the stores for flour, pork, clothing, whiskey, guns, and ammunition, allowing others to flee for Fort Ridgely, fourteen miles away.

[8]: 31 Sibley had no previous military experience, but was familiar with the Dakota and the leaders of the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, having traded among them since arriving in the Minnesota River Valley 28 years beforehand as a representative of the American Fur Company.

[8][46]: 147–148 After receiving a message written by Lieutenant Timothy J. Sheehan about the seriousness of the attacks on Fort Ridgely, Colonel Sibley decided to wait for reinforcements, arms, ammunition and provisions before leaving St. Peter.

On August 28, Governor Ramsey sent Judge Charles Eugene Flandrau to the Blue Earth country to secure the state's southern and southwestern frontier, extending from New Ulm to the northern border of Iowa.

[66]: 305 The company included members of the 6th Minnesota Infantry Regiment and mounted men of the Cullen Frontier Guards,[67] as well as teams and teamsters sent to bury the dead, accompanied by approximately 20 civilians who had asked to join the burial party.

[8]: 87 Finally, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton formed the Department of the Northwest on September 6, 1862 and appointed General John Pope, who had been defeated in the Second Battle of Bull Run, to command it, with orders to quell the violence "using whatever force may be necessary.

Recognizing the severity of the crisis, Pope instructed Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley to move decisively, but struggled to secure additional Federal troops in time for the war effort.

[12] Sibley planned to meet Little Crow's men on the open plains above the Yellow Medicine River, where he believed his better organized, better equipped forces with their rifled muskets and artillery with exploding shells would have an advantage against the Dakota with their double-barreled shotguns.

[75] Chief Little Crow and his soldiers' lodge received word that Sibley's troops had reached the Lower Sioux Agency and would arrive at the area below the Yellow Medicine River around September 21.

[49][77] On the night of September 22, Little Crow, Chief Big Eagle and others carefully moved their men into position under cover of darkness, often with a clear view of Sibley's troops, who were unaware of their presence.

Much to the surprise of the Dakota, at about 7 am on September 23, a group of soldiers from the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment left camp in four or five wagons, on an unauthorized trip to forage for potatoes at the Upper Sioux Agency.

[73] About half a mile from camp, after crossing the bridge over the creek to the other side of the ravine and ascending 100 yards into the high prairie, the lead wagon belonging to Company G was attacked by a squad of 25 to 30 Dakota men who sprang up and began shooting.

[66] Marshall deployed his men equally in dugouts and in a skirmish line which fired as they gradually crawled forward and finally charged, successfully driving the Dakota back from the ravine.

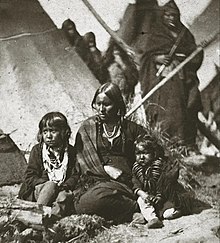

[18] The captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (mixed-race) and 107 whites, mostly women and children, who had been held hostage by the "hostile" Dakota camp, which broke up as Little Crow and some of his followers fled to the northern plains.

In the nights that followed, a growing number of Mdewakanton men who had participated in battles quietly joined the "friendly" Dakota at Camp Release; many did not want to spend winter on the plains and were persuaded by Sibley's earlier promise to punish only those who had killed settlers.

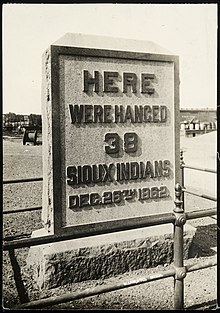

[81] A few weeks prior to the execution, the convicted men were sent to Mankato, while 1,658 Natives and "mixed bloods", including their families and the "friendly" Dakota, were sent to a compound south of Fort Snelling.

[citation needed] Legal historian Carol Chomsky writes in the Stanford Law Review: The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission composed completely of Minnesota settlers.

[citation needed] Even partial clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered white Minnesotans "reasonable compensation for the depredations committed.

[103] Using the general public's fascination to their advantage, they began to craft ornamental items, such as finger rings, bead work, wooden fish, hatchets, and bows and arrows, and sold them to support their needs within the internment camp, such as blankets, clothing, and food.

[103][104] During their incarceration, the Dakota continued to struggle for their rightful compensation of the lands ceded by treaty, as well as their freedom, even enlisting the help of sympathetic camp guards and settlers to assist.

For example, the compilation by Charles Bryant, titled Indian Massacre in Minnesota, included these graphic descriptions of the murders of settlers on the night of August 18, taken from an interview with Justina Kreiger about events she had not witnessed directly:[13]: 99 Mr. Massipost had two daughters, young ladies, intelligent and accomplished.

Throckmorten and Clerk Gorman we saw those of strangers; and instead of her usual lading of merchandise for our merchants, she was crowded from stem to stern, and from hold to hurricane deck with old squaws and papooses – about 1,400 in all – the non combative remnants of the Santee Sioux of Minnesota, en route to their new home….