Dalkon Shield

The Dalkon Shield was found to cause severe injury to a disproportionately large percentage of women, which eventually led to numerous lawsuits, in which juries awarded millions of dollars in compensatory and punitive damages.

Davis was a physician working as a gynecologist with an interest in limiting the effects of overpopulation in the world, as part of the Zero population growth theory popular in the 1960s.

"[1] He setup a family planning clinic for the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1964, with the help of the Ortho Pharmaceutical Company, with many of his public patients being poor and black Baltimoreans.

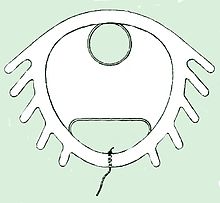

The design they came up with had a closed center (so as to not pose a risk of strangling the intestines if it migrated to the abdomen), and increase its surface area (and perhaps effectiveness) made of EVA (which had been approved by the FDA for use in food packaging), and fins were added to make it less likely to dislodge.

[1] Previous IUD designs had used a monofilament plastic string to reduce the chance of wicking bacteria from the non-sterile vaginal canal to the sterile uterus.

However, this was later found to have numerous flaws; in the five months after the study was concluded, pregnancy rates were at 3-5%, it didn't have enough participants to give statistically significant results, and the average woman was enrolled for 5 months of the 12-month study; women who dropped out were not included in the results; some women were included after they had found success with the IUD, and Davis had recommended using spermicide during the most fertile days of patients cycles.

In the time between the study's submission to the journal and its publication, several women had become pregnant, making the pregnancy rate 3-5%, and taking it from better than other IUDs and oral contraceptives on the market to worst.

[5] Looking for a large retailer with marketing experience to sell their product, Earl met with a representative from A.H. Robins Company and sold them ownership rights and royalties.

[6] The Dalkon Shield was promoted as a safer alternative compared to birth control pills, which at the time were the subject of many safety concerns.

[6][8][9][10] Initial reports in the medical literature raised questions about whether its efficacy in preventing pregnancy and expulsion rate were as good as those claimed by the manufacturer, but failed to detect the tendency of the device to cause septic abortion and other severe infections.

[1] In June 1973, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a survey of 34,544 physicians with practices in gynecology or obstetrics regarding women who had been hospitalized or had died with complications related to the use of an IUD in the previous 6 months.

Based on these data, the CDC estimated an IUD-related fatality rate of 3 per million users per year of use, which it compared favorably to the mortality risks associated with pregnancy and other forms of contraception.

[14] That same month, A.H. Robins suspended sales of the device in the United States at the urging of the Food and Drug Administration, but continued to sell it overseas.

The company's representatives argued that pelvic infections have a wide variety of causes, and that the Dalkon Shield was no more dangerous than other forms of birth control.

[18] In 1971, 5 months after the IUD was released, the string was found to wick bacteria into the uterus by a quality control supervisor, and the company chose to change nothing.

[19] In 1984, 10 years after it was taken off the market in the US, the company put out newspaper, magazine, and television ads warning people of the risks and offering to pay for the shield's removal.

The federal judge, Miles W. Lord, attracted public commentary for his judgments, holding the corporate heads personally accountable, saying "Your company in the face of overwhelming evidence denies its guilt and continues its monstrous mischief.