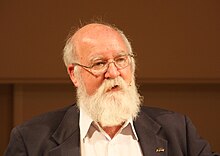

Daniel Dennett

Daniel Clement Dennett III (March 28, 1942 – April 19, 2024) was an American philosopher and cognitive scientist.

[9] Dennett was the co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies and the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy at Tufts University in Massachusetts.

[15][16][17] Dennett spent part of his childhood in Lebanon,[10] where, during World War II, his father, who had a PhD in Islamic studies from Harvard University, was a covert counter-intelligence agent with the Office of Strategic Services posing as a cultural attaché to the American Embassy in Beirut.

"[22][23] In 1965, Dennett received his DPhil in philosophy at the University of Oxford, where he studied under Gilbert Ryle and was a member of Hertford College.

[24][10] His doctoral dissertation was entitled The Mind and the Brain: Introspective Description in the Light of Neurological Findings; Intentionality.

[26] Dennett described himself as "an autodidact—or, more properly, the beneficiary of hundreds of hours of informal tutorials on all the fields that interest me, from some of the world's leading scientists".

[29]While other philosophers have developed two-stage models, including William James, Henri Poincaré, Arthur Compton, and Henry Margenau, Dennett defended this model for the following reasons: These prior and subsidiary decisions contribute, I think, to our sense of ourselves as responsible free agents, roughly in the following way: I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: "That's enough.

[30]Leading libertarian philosophers such as Robert Kane have rejected Dennett's model, specifically that random chance is directly involved in a decision, on the basis that they believe this eliminates the agent's motives and reasons, character and values, and feelings and desires.

Kane says: [As Dennett admits,] a causal indeterminist view of this deliberative kind does not give us everything libertarians have wanted from free will.

[32] Dennett remarked in several places (such as "Self-portrait", in Brainchildren) that his overall philosophical project remained largely the same from his time at Oxford onwards.

Later he asserts, "These yield, over the course of time, something rather like a narrative stream or sequence, which can be thought of as subject to continual editing by many processes distributed around the brain, ..." (p. 135, emphasis in the original).

In this work, Dennett's interest in the ability of evolution to explain some of the content-producing features of consciousness is already apparent, and this later became an integral part of his program.

This view is rejected by neuroscientists Gerald Edelman, Antonio Damasio, Vilayanur Ramachandran, Giulio Tononi, and Rodolfo Llinás, all of whom state that qualia exist and that the desire to eliminate them is based on an erroneous interpretation on the part of some philosophers regarding what constitutes science.

My refusal to play ball with my colleagues is deliberate, of course, since I view the standard philosophical terminology as worse than useless—a major obstacle to progress since it consists of so many errors.

[46] This idea is in conflict with the evolutionary philosophy of paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who preferred to stress the "pluralism" of evolution (i.e., its dependence on many crucial factors, of which natural selection is only one).

Dennett was referred to as one of the "Four Horsemen of New Atheism", along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens.

[52] The research and stories Dennett and LaScola accumulated during this project were published in their 2013 co-authored book, Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind.

[53] Dennett wrote about and advocated the notion of memetics as a philosophically useful tool, his last work on this topic being his "Brains, Computers, and Minds", a three-part presentation through Harvard's MBB 2009 Distinguished Lecture Series.

Dennett was critical of postmodernism, having said: Postmodernism, the school of "thought" that proclaimed "There are no truths, only interpretations" has largely played itself out in absurdity, but it has left behind a generation of academics in the humanities disabled by their distrust of the very idea of truth and their disrespect for evidence, settling for "conversations" in which nobody is wrong and nothing can be confirmed, only asserted with whatever style you can muster.

While approving of the increase in efficiency that humans reap by using resources such as expert systems in medicine or GPS in navigation, Dennett saw a danger in machines performing an ever-increasing proportion of basic tasks in perception, memory, and algorithmic computation because people may tend to anthropomorphize such systems and attribute intellectual powers to them that they do not possess.

[58] In the 1990s, Dennett collaborated with a group of computer scientists at MIT to attempt to develop a humanoid, conscious robot, named "Cog".

[61] Dennett believed, as of the book's publication in 2017, that the prospect of superintelligence (AI massively exceeding the cognitive performance of humans in all domains) was at least 50 years away, and of far less pressing significance than other problems the world faces.

While he supported scientific realism, advocating that entities and phenomena posited by scientific theories exist independently of our perceptions, he leant towards instrumentalism concerning certain theoretical entities, valuing their explanatory and predictive utility, as showing in his discussion of real patterns.

He posited that our discourse about reality is mediated by our cognitive and linguistic capacities, marking a departure from Naïve realism.

[64] Dennett's philosophical stance on realism was intricately connected to his views on instrumentalism and the theory of real patterns.