Upanishads

[2][note 1] They are the most recent addition to the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, and deal with meditation, philosophy, consciousness, and ontological knowledge.

[3][4][5] While among the most important literature in the history of Indian religions and culture, the Upanishads document a wide variety of "rites, incantations, and esoteric knowledge"[6] departing from Vedic ritualism and interpreted in various ways in the later commentarial traditions.

[11][12] The mukhya Upanishads are found mostly in the concluding part of the Brahmanas and Aranyakas[13] and were, for centuries, memorized by each generation and passed down orally.

The mukhya Upanishads predate the Common Era, but there is no scholarly consensus on their date, or even on which ones are pre- or post-Buddhist.

[20] The mukhya Upanishads, along with the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutra (known collectively as the Prasthanatrayi),[21] are interpreted in divergent ways in the several later schools of Vedanta.

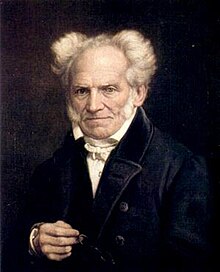

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was deeply impressed by the Upanishads and called them "the most profitable and elevating reading which ... is possible in the world.

"[23] Modern era Indologists have discussed the similarities between the fundamental concepts in the Upanishads and the works of major Western philosophers.

Monier-Williams' Sanskrit Dictionary notes – "According to native authorities, Upanishad means setting to rest ignorance by revealing the knowledge of the supreme spirit.

[35] The ancient Upanishads are embedded in the Vedas, the oldest of Hinduism's religious scriptures, which some traditionally consider to be apauruṣeya, which means "not of a man, superhuman"[36] and "impersonal, authorless".

[37][38][39] The Vedic texts assert that they were skillfully created by Rishis (sages), after inspired creativity, just as a carpenter builds a chariot.

[40] The various philosophical theories in the early Upanishads have been attributed to famous sages such as Yajnavalkya, Uddalaka Aruni, Shvetaketu, Shandilya, Aitareya, Balaki, Pippalada, and Sanatkumara.

Indologist Patrick Olivelle says that "in spite of claims made by some, in reality, any dating of these documents [early Upanishads] that attempts a precision closer than a few centuries is as stable as a house of cards".

Bronkhorst places even the oldest of the Upanishads, such as the Brhadaranyaka as possibly still being composed at "a date close to Katyayana and Patañjali [the grammarian]" (i.e., c. 2nd century BCE).

[20] The main Shakta Upanishads, for example, mostly discuss doctrinal and interpretative differences between the two principal sects of a major Tantric form of Shaktism called Shri Vidya upasana.

The many extant lists of authentic Shakta Upaniṣads vary, reflecting the sect of their compilers, so that they yield no evidence of their "location" in Tantric tradition, impeding correct interpretation.

[101] The Mundaka Upanishad declares how man has been called upon, promised benefits for, scared unto and misled into performing sacrifices, oblations and pious works.

[102][103] The Maitri Upanishad states,[104] The performance of all the sacrifices, described in the Maitrayana-Brahmana, is to lead up in the end to a knowledge of Brahman, to prepare a man for meditation.

According to Nakamura, the Brahmasutras see Atman and Brahman as both different and not-different, a point of view which came to be called bhedabheda in later times.

[124] The Upanishads describe the universe, and the human experience, as an interplay of Purusha (the eternal, unchanging principles, consciousness) and Prakṛti (the temporary, changing material world, nature).

[140][141] King states that Gaudapada's main work, Māṇḍukya Kārikā, is infused with philosophical terminology of Buddhism, and uses Buddhist arguments and analogies.

[157] The Upanishads, according to the Vishishtadvaita school, teach individual souls to be of the same quality as the Brahman, but quantitatively distinct.

[160][161][162] In the Vishishtadvaita school, the Upanishads are interpreted to be teaching about Ishvara (Vishnu), who is the seat of all auspicious qualities, with all of the empirically perceived world as the body of God who dwells in everything.

Platonic psychology with its divisions of reason, spirit and appetite, also bears resemblance to the three Guṇas in the Indian philosophy of Samkhya.

[172][173][note 10] Various mechanisms for such a transmission of knowledge have been conjectured including Pythagoras traveling as far as India; Indian philosophers visiting Athens and meeting Socrates; Plato encountering the ideas when in exile in Syracuse; or, intermediated through Persia.

[176][177] The Upanishads have been translated into various languages including Persian, Italian, Urdu, French, Latin, German, English, Dutch, Polish, Japanese, Spanish and Russian.

[199] The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer read the Latin translation and praised the Upanishads in his main work, The World as Will and Representation (1819), as well as in his Parerga and Paralipomena (1851).

Americans, such as Emerson and Thoreau embraced Schelling's interpretation of Kant's Transcendental idealism, as well as his celebration of the romantic, exotic, mystical aspect of the Upanishads.

[205] The poet T. S. Eliot, inspired by his reading of the Upanishads, based the final portion of his famous poem The Waste Land (1922) upon one of its verses.

The Upanishads insisted on oneness of soul, excluded all plurality, and therefore, all proximity in space, all succession in time, all interdependence as cause and effect, and all opposition as subject and object.

The "know thyself" of the Upanishads means, know thy true self, that which underlines thine Ego, and find it and know it in the highest, the eternal Self, the One without a second, which underlies the whole world.