Dandy

A dandy could be a self-made man both in person and persona, who emulated the aristocratic style of life regardless of his middle-class origin, birth, and background, especially during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain.

In the metaphysical phase of dandyism, the poet Charles Baudelaire portrayed the dandy as an existential reproach to the conformity of contemporary middle-class men, cultivating the idea of beauty and aesthetics akin to a living religion.

The dandy lifestyle, in certain respects, "comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" as an approach to living daily life,[5] while its followers "have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking … [because] Dandyism is a form of Romanticism.

Thus, the dandy represented a nostalgic yearning for feudal values and the ideals of the perfect gentleman as well as the autonomous aristocrat – referring to men of self-made person and persona.

The social existence of the dandy, paradoxically, required the gaze of spectators, an audience, and readers who consumed their "successfully marketed lives" in the public sphere.

The lyrics, particularly the reference to "stuck a feather in his hat" and "called it Macoroni," suggested that adorning fashionable attire (a fine horse and gold-braided clothing) was what set the dandy apart from colonial society.

[10] In other cultural contexts, an Anglo–Scottish border ballad dated around 1780 utilized dandy in its Scottish connotation and not the derisive British usage populated in colonial North America.

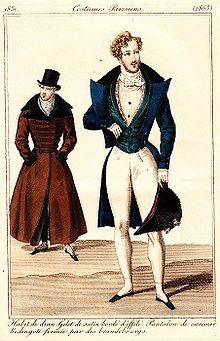

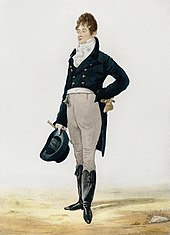

[11] Since the 18th century, contemporary British usage has drawn a distinction between a dandy and a fop, with the former characterized by a more restrained and refined wardrobe compared to the flamboyant and ostentatious attire of the latter.

Upon coming of age in 1799, Brummell received a paternal inheritance of thirty thousand pounds sterling, which he squandered on a high life of gambling, lavish tailors, and visits to brothels.

[18]In the mid-19th century, amidst the restricted palette of muted colors for men's clothing, the English dandy dedicated meticulous attention to the finer details of sartorial refinement (design, cut, and style), including: "The quality of the fine woollen cloth, the slope of a pocket flap or coat revers, exactly the right colour for the gloves, the correct amount of shine on boots and shoes, and so on.

It is important to acknowledge Black dandyism as distinct and a highly political effort at challenging stereotypes of race, class, gender, and nationality.

According to the standards of the day, it was ludicrous and hilarious to see a person of perceived lower social standing donning fashionable attire and "putting on airs."

The representation of Dandy Jim, while potentially rooted in caricature or exaggeration, nonetheless contribute to the broader cultural landscape surrounding Black dandyism and its portrayal in American folk music.

Through the analysis of clothing, aesthetics, and societal norms, Amann examines how dandyism emerged as a means of asserting identity, power, and autonomy in the midst of revolutionary change.

Critics of the act expressed fear regarding the association between wearing hair powder and "a tendency to produce a famine,” and those who did so would “run the further risque of being knocked on the head”.

To protest the tax and the war against France was to embrace a new aesthetic of invisibility, wherein individuals favored natural attire and simplicity in order to blend into the social fabric rather than stand out.

According to Elisa Glick, the dandy's attention to their appearance and their engagement "consumption and display of luxury goods" can be read as an expression of capitalist commodification.

[30] However, interestingly, this meticulous attention to personal appearance can also be seen as an assertion of individuality and thus a revolt against capitalism's emphasis on mass production and utilitarianism.

"[31] He argues that this simultaneous abiding by and also ignorance of capitalist social pressures speaks to what he calls a “playful attitude towards life’s conventions."

Not only does the dandy play with traditional conceptions of gender, but also with the socioeconomic norms of the society they inhabit; he agrees the importance that dandyism places on uniquely personal style directly opposes capitalism's call for conformity.

"[32] This process "creates a market for new social models, with the dandy as a prime example of how individuals navigate and resist the pressures of a capitalist society."

In the 12th century, cointerrels (male) and cointrelles (female) emerged, based upon coint,[33] a word applied to things skillfully made, later indicating a person of beautiful dress and refined speech.

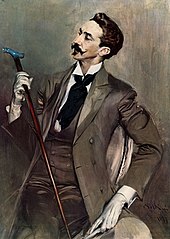

The illustration, by E. J. Sullivan , is from an 1898 edition of the novel Sartor Resartus (1831), by Thomas Carlyle.