Olympic National Park

[3] The park has four regions: the Pacific coastline, alpine areas, the west-side temperate rainforest, and the forests of the drier east side.

[5] President Theodore Roosevelt originally designated the park as Mount Olympus National Monument on March 2, 1909.

In 1976, Olympic National Park was designated by UNESCO as an International Biosphere Reserve, and in 1981 as a World Heritage Site.

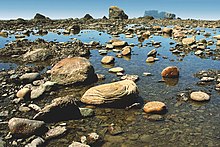

As stated in the foundation document:[12] The purpose of Olympic National Park is to preserve for the benefit, use, and enjoyment of the people, a large wilderness park containing the finest sample of primeval forest of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Douglas fir, and western red cedar in the entire United States; to provide suitable winter range and permanent protection for the herds of native Roosevelt elk and other wildlife indigenous to the area; to conserve and render available to the people, for recreational use, this outstanding mountainous country, containing numerous glaciers and perpetual snow fields, and a portion of the surrounding verdant forests together with a narrow strip along the beautiful Washington coast.The coastal portion of the park is a rugged, sandy beach along with a strip of adjacent forest.

The coastal strip is more readily accessible than the interior of the Olympics; due to the difficult terrain, very few backpackers venture beyond casual day-hiking distances.

From the trailhead at Ozette Lake, a 3-mile (4.8 km) leg of the trail is a boardwalk-enhanced path through near primal coastal cedar swamp.

The mostly unaltered Hoh River, toward the south end of the park, discharges large amounts of naturally eroded timber and other drift, which moves north, enriching the beaches.

Even today driftwood deposits form a commanding presence, biologically as well as visually, giving a taste of the original condition of the beach viewable to some extent in early photos.

Drift material often comes from a considerable distance; the Columbia River formerly contributed huge amounts to the Northwest Pacific coasts.

The mountains themselves are products of accretionary wedge uplifting related to the Juan De Fuca Plate subduction zone.

[citation needed] The number of glaciers within the national park declined from 266 in 1982 to 184 by 2009 due to the effects of climate change.

Mount Olympus receives a large amount of snow and consequently has the greatest glaciation of any non-volcanic peak in the contiguous United States outside of the North Cascades.

[22] Because the park sits on an isolated peninsula, with a high mountain range dividing it from the land to the south, it developed many endemic plant and animal species (like the Olympic Marmot, Piper's bellflower and Flett's violet).

As a result, scientists have declared it a biological reserve and studied its unique species to better understand how plants and animals evolve.

[28][29] According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the plant hardiness zone at Hoh Rainforest Visitor Center is 8a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of 14.5 °F (−9.7 °C).

However, recent reviews of the record,[citation needed] coupled with systematic archaeological surveys of the mountains (Olympic and other Northwest ranges) are pointing to much more extensive tribal use of especially the subalpine meadows than seemed formerly to be the case.

The formal record of a proposal for a new national park on the Olympic Peninsula begins with the expeditions of well-known figures Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil and Judge James Wickersham, during the 1890s.

These notables met in the Olympic wilderness while exploring, and subsequently combined their political efforts to have the area placed within some protected status.

[34] Following unsuccessful efforts in the Washington State Legislature to further protect the area in the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt created Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909, primarily to protect the subalpine calving grounds and summer range of the Roosevelt elk herds native to the Olympics.

Public desire for preservation of some of the area grew until President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a bill creating a national park in 1938.

[38] Animals that inhabit this national park include chipmunks, squirrels, skunks, six species of bats, weasels, coyotes, muskrats, fishers, river otters, beavers, red foxes, mountain goats, martens, bobcats, black bears, Canadian lynxes, moles, snowshoe hares, shrews, and cougars.

Birds that fly in this park including raptors are Winter wrens, Canada jays, Hammond's flycatchers, Wilson's warblers, Blue Grouses, Pine siskins, ravens, spotted owls, Red-breasted nuthatches, Golden-crowned kinglets, Chestnut-backed chickadees, Swainson's thrushes, Red crossbills, Hermit thrushes, Olive-sided flycatchers, bald eagles, Western tanagers, Northern pygmy owls, Townsend's warblers, Townsend's solitaires, Vaux's swifts, band-tailed pigeons, and evening grosbeaks.

Constructed in the 1950s, it contained a 3D topographical map of the Olympics, a media center which showed nature documentaries of the area as well as other interpretive exhibits, and a gift shop.

Upon removal, the park will revegetate the slopes and river bottoms to prevent erosion and speed up ecological recovery.