Darcy's law

Darcy's law is an equation that describes the flow of a fluid through a porous medium and through a Hele-Shaw cell.

The law was formulated by Henry Darcy based on results of experiments[1] on the flow of water through beds of sand, forming the basis of hydrogeology, a branch of earth sciences.

It is analogous to Ohm's law in electrostatics, linearly relating the volume flow rate of the fluid to the hydraulic head difference (which is often just proportional to the pressure difference) via the hydraulic conductivity.

One application of Darcy's law is in the analysis of water flow through an aquifer; Darcy's law along with the equation of conservation of mass simplifies to the groundwater flow equation, one of the basic relationships of hydrogeology.

Based on experimental results by his colleagues Wyckoff and Botset, Muskat and Meres also generalized Darcy's law to cover a multiphase flow of water, oil and gas in the porous medium of a petroleum reservoir.

The generalized multiphase flow equations by Muskat and others provide the analytical foundation for reservoir engineering that exists to this day.

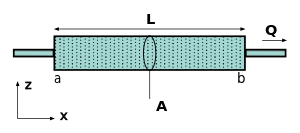

In the integral form, Darcy's law, as refined by Morris Muskat, in the absence of gravitational forces and in a homogeneously permeable medium, is given by a simple proportionality relationship between the volumetric flow rate

In the (less general) integral form, the volumetric flux and the pressure gradient correspond to the ratios:

The corresponding hydraulic conductivity is therefore: Darcy's law is a simple mathematical statement which neatly summarizes several familiar properties that groundwater flowing in aquifers exhibits, including: A graphical illustration of the use of the steady-state groundwater flow equation (based on Darcy's law and the conservation of mass) is in the construction of flownets, to quantify the amount of groundwater flowing under a dam.

Typically any flow with a Reynolds number less than one is clearly laminar, and it would be valid to apply Darcy's law.

The Reynolds number (a dimensionless parameter) for porous media flow is typically expressed as where ν is the kinematic viscosity of water, q is the specific discharge (not the pore velocity — with units of length per time), d is a representative grain diameter for the porous media (the standard choice is math|d30, which is the 30% passing size from a grain size analysis using sieves — with units of length).

For stationary, creeping, incompressible flow, i.e. D(ρui)/Dt ≈ 0, the Navier–Stokes equation simplifies to the Stokes equation, which by neglecting the bulk term is: where μ is the viscosity, ui is the velocity in the i direction, and p is the pressure.

Assuming the viscous resisting force is linear with the velocity we may write: where φ is the porosity, and kij is the second order permeability tensor.

This gives the velocity in the n direction, which gives Darcy's law for the volumetric flux density in the n direction, In isotropic porous media the off-diagonal elements in the permeability tensor are zero, kij = 0 for i ≠ j and the diagonal elements are identical, kii = k, and the common form is obtained as below, which enables the determination of the liquid flow velocity by solving a set of equations in a given region.

Another derivation of Darcy's law is used extensively in petroleum engineering to determine the flow through permeable media — the most simple of which is for a one-dimensional, homogeneous rock formation with a single fluid phase and constant fluid viscosity.

The petroleum industry is, therefore, using a generalized Darcy equation for multiphase flow developed by Muskat et alios.

[9] The papers will either take the coffee permeability to be constant as a simplification or will measure change through the brewing process.

Darcy's law can be expressed very generally as: where q is the volume flux vector of the fluid at a particular point in the medium, h is the total hydraulic head, and K is the hydraulic conductivity tensor, at that point.

For flows in porous media with Reynolds numbers greater than about 1 to 10, inertial effects can also become significant.

This term is able to account for the non-linear behavior of the pressure difference vs flow data.

In this case, the inflow performance calculations for the well, not the grid cell of the 3D model, are based on the Forchheimer equation.

The effect of this is that an additional rate-dependent skin appears in the inflow performance formula.

For gas flow in small characteristic dimensions (e.g., very fine sand, nanoporous structures etc.

For a flow in this region, where both viscous and Knudsen friction are present, a new formulation needs to be used.

Knudsen presented a semi-empirical model for flow in transition regime based on his experiments on small capillaries.

The Klinkenberg parameter b is dependent on permeability, Knudsen diffusivity and viscosity (i.e., both gas and porous medium properties).

This form is more mathematically rigorous but leads to a hyperbolic groundwater flow equation, which is more difficult to solve and is only useful at very small times, typically out of the realm of practical use.

Another extension to the traditional form of Darcy's law is the Brinkman term, which is used to account for transitional flow between boundaries (introduced by Brinkman in 1949[16]), where β is an effective viscosity term.

This correction term accounts for flow through medium where the grains of the media are porous themselves, but is difficult to use, and is typically neglected.

In fine-grained sediments, the dimensions of interstices are small; thus, the flow is laminar.