Darwin's Dangerous Idea

Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life is a 1995 book by the philosopher Daniel Dennett, in which the author looks at some of the repercussions of Darwinian theory.

Dennett makes this case on the basis that natural selection is a blind process, which is nevertheless sufficiently powerful to explain the evolution of life.

Dennett noted discomfort with Darwinism among not only lay people but also even academics and decided it was time to write a book dealing with the subject.

[3] Darwin's Dangerous Idea is not meant to be a work of science, but rather an interdisciplinary book; Dennett admits that he does not understand all of the scientific details himself.

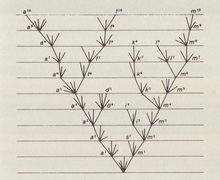

However, there are also "Forced Moves" or "Good Tricks" that will be discovered repeatedly, either by natural selection (see convergent evolution) or human investigation.

The first chapter of part II, "Darwinian Thinking in Biology", asserts that life originated without any skyhooks, and the orderly world we know is the result of a blind and undirected shuffle through chaos.

Related to the engineering concept of optimization, the next chapter deals with adaptationism, which Dennett endorses, calling Gould and Lewontin's "refutation" of it[9] an illusion.

The tenth chapter, entitled "Bully for Brontosaurus", is an extended critique of Stephen Jay Gould, who Dennett feels has created a distorted view of evolution with his popular writings; his "self-styled revolutions" against adaptationism, gradualism and other orthodox Darwinism all being false alarms.

The final chapter of part II dismisses directed mutation, the inheritance of acquired traits and Teilhard's "Omega Point", and insists that other controversies and hypotheses (like the unit of selection and Panspermia) have no dire consequences for orthodox Darwinism.

Dennett criticizes Noam Chomsky's perceived resistance to the evolution of language, its modeling by artificial intelligence, and reverse engineering.

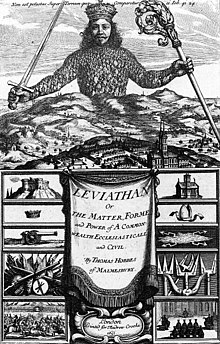

[12] The subject then moves on to the origin and evolution of morality, beginning with Thomas Hobbes[13] (who Dennett calls "the first sociobiologist") and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Dennett does not believe there is much hope of discovering an algorithm for doing the right thing, but expresses optimism in our ability to design and redesign our approach to moral problems.

For this reason he indicates deliberately that the complex fruits of the tree of life are in a very meaningful sense "designed"—even though he does not believe evolution was guided by a higher intelligence.

This is where Dennett draws parallels from the “universal acid” to Darwin's idea: it eats through just about every traditional concept, and leaves in its wake a revolutionized world-view, with most of the old landmarks still recognizable, but transformed in fundamental ways.

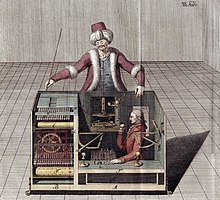

In philosophical arguments concerning the reducibility (or otherwise) of the human mind, Dennett's concept pokes fun at the idea of intelligent design emanating from on high, either originating from one or more gods, or providing its own grounds in an absurd, Munchausen-like bootstrapping manner.

If an argued case can be discerned at all amid the slurs and sneers, it would have to be described as an effort to claim that I have, thanks to some literary skill, tried to raise a few piddling, insignificant, and basically conventional ideas to "revolutionary" status, challenging what he takes to be the true Darwinian scripture.

Since Dennett shows so little understanding of evolutionary theory beyond natural selection, his critique of my work amounts to little more than sniping at false targets of his own construction.