Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (/ˈdæʃəl ˈhæmɪt/ DASH-əl HAM-it;[2] May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories.

He had an elder sister, Aronia, and a younger brother, Richard Jr.[9] Known as Sam, Hammett was baptized a Catholic[10] and grew up in Philadelphia and Baltimore.

He spent most of his time in the Army as a patient at Cushman Hospital in Tacoma, Washington, where he met a nurse, Josephine Dolan, whom he married on July 7, 1921, in San Francisco.

[17] Shortly after the birth of their second child, health services nurses informed Dolan that, owing to Hammett's tuberculosis, she and the children should not live with him full time.

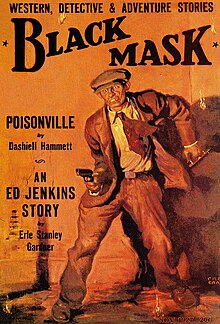

"[25] The bulk of his early work, featuring a nameless private investigator, The Continental Op, appeared in leading crime-fiction pulp magazine Black Mask.

[26] Because of a disagreement with editor Philip C. Cody about money owed from previous stories, Hammett briefly stopped writing for Black Mask in 1926.

[27] Both these novels and his third, The Maltese Falcon, and fourth, The Glass Key, were first serialized in Black Mask before being revised and edited for publication by Alfred A. Knopf.

Why he moved away from fiction is not certain; Hellman speculated in a posthumous collection of Hammett's novels, "I think, but I only think, I know a few of the reasons: he wanted to do new kind of work; he was sick for many of those years and getting sicker.

[29] The French novelist André Gide thought highly of Hammett, stating: "I regard his Red Harvest as a remarkable achievement, the last word in atrocity, cynicism and horror.

Dashiell Hammett's dialogues, in which every character is trying to deceive all the others and in which the truth slowly becomes visible through a fog of deception, can be compared only with the best in Hemingway.

[31] On May 1, 1935, Hammett joined the League of American Writers (1935–1943), whose members included Lillian Hellman, Alexander Trachtenberg of International Publishers, Frank Folsom, Louis Untermeyer, I. F. Stone, Myra Page, Millen Brand, Clifford Odets, and Arthur Miller.

)[32] He suspended his anti-fascist activities when, as a member (and in 1941 president) of the League of American Writers, he served on its Keep America Out of War Committee in January 1940 during the period of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

One Hammett biographer, Richard Layman, calls such interpretations "imaginative", but he nonetheless objects to them, since, among other reasons, no "masses of politically dispossessed people" are in this novel.

Herbert Ruhm found that contemporary left-wing media already viewed Hammett's writing with skepticism, "perhaps because his work suggests no solution: no mass-action... no individual salvation... no Emersonian reconciliation and transcendence".

For fear of his radical tendencies, he was transferred to the Headquarters Company where he edited an Army newspaper entitled The Adakian along with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade veteran (and later professor) Robert Garland Colodny.

[43] The CRC's bail fund gained national attention on November 4, 1949, when bail in the amount of "$260,000 in negotiable government bonds" was posted "to free eleven men appealing against their convictions under the Smith Act for criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the United States government by force and violence."

On July 2, 1951, their appeals exhausted, four of the convicted men fled rather than surrender themselves to federal agents and begin serving their sentences.

During the hearing, Hammett refused to provide the information the government wanted, specifically the list of contributors to the bail fund, "people who might be sympathetic enough to harbor the fugitives.

[41][44][45][46] Hammett served time in a West Virginia federal penitentiary, where, according to Lillian Hellman, he was assigned to clean toilets.

[47][48] Hellman noted in her eulogy of Hammett that he submitted to prison rather than reveal the names of the contributors to the fund because "he had come to the conclusion that a man should keep his word.

"[51] Hellman wrote that during the 1950s, Hammett became "a hermit", his decline evident in the clutter of his rented "ugly little country cottage", where "signs of sickness were all around: now the phonograph was unplayed, the typewriter untouched, the beloved foolish gadgets unopened in their packages.

"[52] He may have meant to start a new literary life with the novel Tulip, but left it unfinished, perhaps because he was "just too ill to care, too worn out to listen to plans or read contracts.

[56] The Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of South Carolina holds the Dashiell Hammett family papers.

Jason Robards won an Oscar for his depiction of Hammett, and Jane Fonda was nominated for her portrayal of Lillian Hellman.

Sam Shepard played Hammett in the 1999 Emmy-nominated biographical television film Dash and Lilly along with Judy Davis as Hellman.

[61] In 2006, Rachel Cohn published the YA novel, Nick & Norah's Infinite Playlist, whose main characters were named for the sleuths in Hammett's Thin Man series.

An important collection, The Big Knockover and Other Stories, edited by Lillian Hellman, helped revive Hammett's literary reputation in the 1960s and fostered a new series of anthologies.

Along with the novels, these later collections have been reprinted in paperback versions under many imprints: Vintage Crime, Black Lizard, Everyman's library.