Magnetic-tape data storage

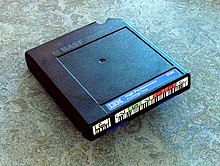

Modern magnetic tape is most commonly packaged in cartridges and cassettes, such as the widely supported Linear Tape-Open (LTO)[1] and IBM 3592 series.

[5] This standard for large computer systems persisted through the late 1980s, with steadily increasing capacity due to thinner substrates and changes in encoding.

[8] The UNISERVO drive recording medium was a thin metal strip of 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) wide nickel-plated phosphor bronze.

Making allowances for the empty space between tape blocks, the actual transfer rate was around 7,200 characters per second.

These were 7-inch (18 cm) reels, often with no fixed length—the tape was sized to fit the amount of data recorded on it as a cost-saving measure.

Stock shots of such vacuum-column tape drives in motion were emblematically representative of computers in movies and television.

The physical beginning and end of usable tape was indicated by reflective adhesive strips of aluminum foil placed on the backside.

Effective density also increased as the interblock gap (inter-record gap) decreased from a nominal 3⁄4 inch (19 mm) on 7-track tape reel to a nominal 0.30 inches (7.6 mm) on a 6250 bpi[clarification needed] 9-track tape reel.

[12] At least partly due to the success of the System/360, and the resultant standardization on 8-bit character codes and byte addressing, 9-track tapes were very widely used throughout the computer industry during the 1970s and 1980s.

LINCtapes and DECtapes had similar capacity and data transfer rate to the diskettes that displaced them, but their access times were on the order of thirty seconds to a minute.

[16] Compact cassettes are logically, as well as physically, sequential; they must be rewound and read from the start to load data.

In 1984 IBM introduced the 3480 family of single reel cartridges and tape drives which were then manufactured by a number of vendors through at least 2004.

As of 2019[update] LTO has completely displaced all other tape technologies in computer applications, with the exception of some IBM 3592 family at the high-end.

[citation needed] Bytes per inch (BPI) is the metric for the density at which data is stored on magnetic media.

[19] The term BPI can mean bytes per inch when the tracks of a particular format are byte-organized, as in nine-track tapes.

[22] Recording method is also an important way to classify tape technologies, generally falling into two categories: linear and scanning.

[citation needed] The linear method arranges data in long parallel tracks that span the length of the tape.

Compared to simple linear recording, using the same tape length and the same number of heads, data storage capacity is substantially higher.

[citation needed] Scanning recording methods write short dense tracks across the width of the tape medium, not along the length.

[citation needed] Helical scan recording writes short dense tracks in a diagonal manner.

By contrast, hard disk technology can perform the equivalent action in tens of milliseconds (3 orders of magnitude faster) and can be thought of as offering random access to data.

Storing metadata in one place and data in another, as is done with disk-based file systems, requires repositioning activity.

There are several algorithms that provide similar results: LZW[citation needed] (widely supported), IDRC (Exabyte), ALDC (IBM, QIC) and DLZ1 (DLT).

Data that is already stored efficiently may not allow any significant compression and a sparse database may offer much larger factors.

[citation needed] Plain text, raw images, and database files (TXT, ASCII, BMP, DBF, etc.)

[31] In 2002, Imation received a US$11.9 million grant from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology for research into increasing the data capacity of magnetic tape.

[33][34] It was further developed by Sony, with announcement in 2017, about reported data density of 201 Gbit/in² (31 Gbit/cm²), giving standard compressed tape capacity of 330 TB.

[36] The technology developed by Fujifilm, called NANOCUBIC, reduces the particulate volume of BaFe magnetic tape, simultaneously increasing the smoothness of the tape, increasing the signal to noise ratio during read and write while enabling high-frequency response.

[citation needed] In December 2020, Fujifilm and IBM announced technology that could lead to a tape cassette with a capacity of 580 terabytes, using strontium ferrite as the recording medium.