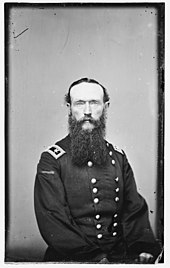

David O. Dodd

Discovering that he did not have a pass, U.S. soldiers questioned him and found that he was carrying a notebook with the locations of Federal troops in the area.

While he did not reveal the source of the information, a young girl named Mary Dodge and her father were summarily escorted back to their home in Vermont.

[1][2] His parents, who were Baptists,[3] had married in a village south of Little Rock and moved to Texas with their first daughter Senhora, where David and his sisters Leonora and Ann Eliza were born.

In 1862 David went to Louisiana and worked as a telegraph operator until crossing the river to join his father and assist him in his sutlery.

In the fall of 1863, after the Union Army occupied Little Rock, David returned to escort his mother and sisters to Mississippi but never left Arkansas.

[4] On December 24, 1863, he sent David Dodd—a minor and therefore assumed neutral—to Little Rock to deliver letters to former associates seeking investments for the tobacco deal.

Mary supported the Southern cause; her father, R. L. Dodge, was a Vermont native on friendly terms with the Northern troops.

[1][4] On December 28, 1863, Dodd visited the Provost Marshal's office at St. John's College (several hundred yards southwest of the arsenal) and had no trouble obtaining a pass through Union lines to rejoin his family in Camden.

As he left Union territory, the guard tore up Dodd's pass since he would no longer need it now that he was in Confederate land.

He went to spend the night with his uncle, Washington Dodd, on the Middle Hot Springs Road southwest of Little Rock.

[1][4] On December 29, 1863, Dodd was stopped by a Union sentry in west Little Rock, near Ten Mile House on Stagecoach Road, and was found to be without a pass.

For identification he showed his small leather notebook, where Union soldiers found his birth certificate and a page with dots and dashes.

David was formally charged as a spy and taken to the military prison (on the site of the present Arkansas State Capitol building).

[5] On January 1, 1864, the trial continued with Dodd represented by attorneys Thomas D. W. Yonley and William Fishback, who was pro-Union and later became Governor of Arkansas.

George Hanna testified that he interrogated Dodd and discovered that he was carrying one pocketbook containing Louisiana money, Confederate money, ten dollars in greenbacks and some Confederate postage stamps; one postal currency holder, one loaded Derringer pistol and a package between his cloths containing letters.

Robert C. Clowery testified that he interpreted the Morse code as containing detailed information about the locations and strengths of Union forces and armaments.

First Lt. George O. Sokalski then testified about the actual Union troop strength and weaponry, which was a match to Dodd's coded message.

[2] On January 8, 1864, David O. Dodd was brought to the grounds of his former school, St. John's, just east of the Little Rock Arsenal, for his hanging.

Others told that a soldier shinnied up the gibbet to grab the noose, twist the rope and raise the condemned off the ground.

"[2] Just prior to the funeral, Union headquarters ordered no spoken or sung words at the memorial service, and that only Dodd's relatives in Union-held territory (two aunts and their husbands) would be allowed to attend.

[6] After hearing the news of their son's execution, Andrew and Lydia Dodd spent the remainder of their lives in ill health.

"[8] In 1908 the Arkansas Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy started raising funds for a stained-glass window in Dodd's honor.

[4] The David O. Dodd window was unveiled at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia, on November 7, 1911, where it was displayed for several years.