Davidian Revolution

Barrow summarises the many and varied goals of David I, all of which began and ended with his determination "to surround his fortified royal residence and its mercantile and ecclesiastical satellites with a ring of close friends and supporters, bound to him and his heirs by feudal obligation and capable of rendering him military service of the most up-to-date kind and filling administrative offices at the highest level".

The central idea is that from the late 10th century onwards the culture and institutions of the old Carolingian heartlands in northern France and western Germany spread to outlying areas, creating a more recognisable "Europe".

In applying this model to Scotland, it would be considered that, as recently as the reign of David's father Máel Coluim III, "peripheral" Scotland had lacked – in relation to the "core" cultural regions of northern France, western Germany and England – respectable Catholic religion, a truly centralised royal government, conventional written documents of any sort, native coins, a single merchant town, as well as the essential castle-building cavalry elite.

[4] This is not to say that the Gaelic matrix into which these additions were disseminated was somehow destroyed or swept away; that was not the way in which the paradigm or "blueprint" of medieval Europe functioned – it was only a guide, one that specialised in amelioration, and not (usually) demolition.

[6] The Normans who came to England adopted this ideology, and soon began attacking the Scottish and Irish Gaelic world as spiritually backward – a mindset which even underlay the hagiography of David's mother Margaret, written by her confessor Thurgot at the instigation of the English royal court.

[7] Yet up until this period, Gaelic monks (often called Céli Dé) from Ireland and Scotland had been pioneering their own kind of ascetic reform both in Great Britain and in continental Europe, where they founded many of their own monastic houses.

[12] The widespread infeftment of foreign knights and the processes by which land ownership was converted from a matter of customary tenure into a matter of feudal or otherwise legally-defined relationships revolutionised the way the Kingdom of Scotland was governed, as did the dispersal and installation of royal agents in the new mottes that were proliferating throughout the realm to staff newly created sheriffdoms and judiciaries for the twin purposes of law enforcement and taxation, bringing Scotland further into the "European" model.

Geoffrey Barrow wrote that David's reign witnessed "a revolution in Scots dynastic law" as well as "fundamental innovations in military organization" and "in the composition and dominant characteristics of its ruling class".

David established large scale feudal lordships in the west of his Cumbrian principality for the leading members of the French military entourage who kept him in power.

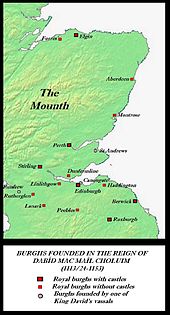

During David I's reign, royal sheriffs had been established in the king's core personal territories; namely, in rough chronological order, at Roxburgh, Scone, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Stirling and Perth.

For instance, Mormaer Causantín of Fife is styled judex magnus (i.e. great Brehon); the Justiciarship of Scotia hence was just as much a Gaelic office modified by Normanisation as it was an import, illustrating Barrow's "balance of New and Old" argument.

Alston silver allowed David to indulge in the "regalian gratification" of his own coinage and to continue his project of attempting to link royal power and economic expansion.

[21] Building programmes depended to a large degree on disposable income; consumption of foreign and exotic commodities broadened; men of ability and ambition found their way to court and entered the service of the king.

Like a seal displaying the king in majesty, the coin broadcast the image of the ruler to his people and, more fundamentally, altered the simple nature of trade.

In part, he made use of the "English" income secured for him by his marriage to Matilda de Senlis in order to finance the construction of the first true towns in Scotland, and these, in turn, allowed the establishment of several more.

[29] The thesis that the "rise of towns" was indirectly responsible for the medieval flourishing of Europe has been accepted, at least in a circumscribed form, from the time of Henri Pirenne, a century ago.

[30] Commerce generated by and the economic privileges granted to merchant towns across northern Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries paid for, in new revenues, the increasing diversification of society and ensured that further growth would occur.

What was of great importance for the future of Scotland was the creation by David of perhaps seven such jurisdictionally licensed communities at ancient royal centres and even at new sites, the latter mainly along his eastern seaboard.

[31] While this could not, at first, have amounted to much more than the nucleus of an immigrant merchant class making use of the established marketplace for the purpose of disposing of the purely local harvest, in both crop and chattels, there is a sense of profound expectation inherent in such foundations.

Several years later, perhaps in 1116, David visited Tiron itself, probably to acquire more monks; in 1128 he transferred Selkirk Abbey to Kelso, nearer Roxburgh, at this point his chief residence.

[51] In the case of the Bishop of Whithorn, the resurrection of that see was the work of Thurstan, Archbishop of York, with King Fergus of Galloway and the cleric Gille Aldan.