Day of the Dead

[16] The historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort has further demonstrated how the ideology known as indigenismo became more and more closely linked to post-revolutionary official projects whereas Hispanismo was identified with conservative political stances.

This exclusive nationalism began to displace all other cultural perspectives, to the point that in the 1930s the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was officially promoted by the government as a substitute for the Spanish Three Kings tradition, with a person dressed up as the deity offering gifts to poor children.

[12] In this context, the Day of the Dead began to be officially isolated from the Catholic Church by the leftist government of Lázaro Cárdenas motivated both by "indigenismo" and left-leaning anti-clericalism.

Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary images which are far closer to those of the European renaissance or the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish War of Independence against Napoleon than to the Mexica tzompantli.

The recent trans-Atlantic connection can also be observed in the pervasive use of couplet in allegories of death and the play Don Juan Tenorio by 19th-century Spanish writer José Zorrilla which is represented on this date both in Spain and in Mexico since the early 19th century due to its ghostly apparitions and cemetery scenes.

[13] Influential Mexican poet and Nobel prize laureate Octavio Paz strongly supported the syncretic view of the Día de Muertos tradition being a continuity of ancient Aztec festivals celebrating death, as is most evident in the chapter "All Saints, Day of the Dead" of his 1950 book-length essay The Labyrinth of Solitude.

As Mexico modernized, the traditional practices that the Spanish had brought to the Americas survived most robustly in rural and less affluent communities, which had high concentrations of indigenous and mestizo populations.

[15] A number of Mexico City's museums and public spaces have played an important part in developing and promoting urban Day of the Dead traditions through altars and installations.

From turn of the millennium until the imposition of the James Bond-inspired parade, remarkable large-scale installations were created on the Zocalo, Mexico City's central square.

[35] Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls, often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.

[25] In some parts of the country, especially the larger cities, children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people's doors for a calaverita, a small gift of candies or money; they also ask passersby for it.

[36] A distinctive literary form exists within this holiday where people write short poems in traditional rhyming verse, called calaveras literarias (lit.

[37][38] This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future which included the words "and all of us were dead", and then proceeding to read the tombstones.

[35] In modern Mexico, calaveras literarias are a staple of the holiday in many institutions and organizations, for example, in public schools, students are encouraged or required to write them as part of the language class.

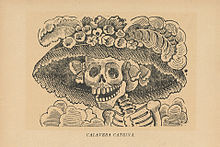

Posada's most famous print, La Calavera Catrina ("The Elegant Skull"), was likely intended as a criticism of Mexican upper-class women who imitated European fashions.

On November 1 of the year after a child's death, the godparents set a table in the parents' home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them), and candles.

At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in exchange for veladoras (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased.

[50] Likewise, Old Town San Diego, California, annually hosts a traditional two-day celebration culminating in a candlelight procession to the historic El Campo Santo Cemetery.

Sponsored by Forest Hills Educational Trust and the folkloric performance group La Piñata, the Day of the Dead festivities celebrated the cycle of life and death.

The project's website contains some of the text and images which explain the origins of some of the customary core practices related to the Day of the Dead, such as the background beliefs and the offrenda (the special altar commemorating one's deceased loved one).

[53] The Made For iTunes multimedia e-book version provides additional content, such as further details; additional photo galleries; pop-up profiles of influential Latino artists and cultural figures over the decades; and video clips[54] of interviews with artists who make Día de Muertos-themed artwork, explanations and performances of Aztec and other traditional dances, an animation short that explains the customs to children, virtual poetry readings in English and Spanish.

For example, in Los Angeles, California, the Self Help Graphics & Art Mexican-American cultural center presents an annual Day of the Dead celebration that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to honor the victims of the Iraq War, highlighting the high casualty rate among Latino soldiers.

In the more central area of San Diego, City Heights celebrates through a public festival in Jeremy Henwood Memorial Park that includes at least 35 altars, lowriders, and entertainment, all for free.

While many regional nuances exist, celebrations generally consist of placing flowers at cemeteries and family burial sites and speaking to deceased relatives.

The pupi di zucchero, thought to be an Arabic cultural import, are often found in the shapes of folkloric characters who represent humanized versions of the souls of the dead.

[65] Acclaimed Sicilian author Andrea Camilleri recounts his Giorno dei Morti experience as boy, as well as the negative cultural impact that WWII era American influence had on the long-held tradition.

On November 9, the family crowns the skulls with fresh flowers, sometimes also dressing them in various garments, and making offerings of cigarettes, coca leaves, alcohol, and various other items in thanks for the year's protection.

[76] In Ecuador the Day of the Dead is observed to some extent by all parts of society, though it is especially important to the indigenous Kichwa peoples, who make up an estimated quarter of the population.

This is typically consumed with guaguas de pan, bread shaped like infants (or, more generally, people), though variations include many pigs—the latter being traditional to the city of Loja.