Dazzle camouflage

Credited to the British marine artist Norman Wilkinson, though with a rejected prior claim by the zoologist John Graham Kerr, it consisted of complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting colours interrupting and intersecting each other.

[10] The American artist Abbott Handerson Thayer had developed a theory of camouflage based on countershading and disruptive coloration, which he had published in the controversial 1909 book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom.

[11][12] Seeing the opportunity to put his theory into service, Thayer wrote to Churchill in February 1915, proposing to camouflage submarines by countershading them like fish such as mackerel, and advocating painting ships white to make them invisible.

[10] His ideas were considered by the Admiralty, but rejected along with Kerr's proposals as being "freak methods of painting ships ... of academic interest but not of practical advantage".

[10] The Admiralty noted that the required camouflage would vary depending on the light, the changing colours of sea and sky, the time of day, and the angle of the sun.

Thayer made repeated and desperate efforts to persuade the authorities, and in November 1915 travelled to England where he gave demonstrations of his theory around the country.

He had a warm welcome from Kerr in Glasgow, and was so enthused by this show of support that he avoided meeting the War Office, who he had been intending to win over, and instead sailed home, continuing to write ineffective letters to the British and American authorities.

[8] Dazzle was created in response to an extreme need, and hosted by an organisation, the Admiralty, which had already rejected an approach supported by scientific theory: Kerr's proposal to use "parti-colouring" based on the known camouflage methods of disruptive coloration and countershading.

[15][e] In 1973, the naval museum curator Robert F. Sumrall[20] (following Kerr[10]) suggested a mechanism by which dazzle camouflage may have sown the kind of confusion that Wilkinson had intended for it.

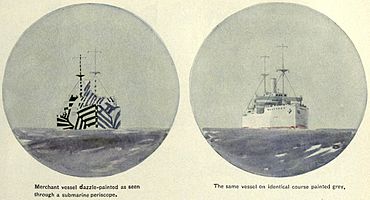

Dazzle, Sumrall argued, was intended to make that hard, as clashing patterns looked abnormal even when the two halves were aligned, something that became more important when submarine periscopes included such rangefinders.

[21] The historian Sam Willis argued that since Wilkinson knew it was impossible to make a ship invisible with paint, the "extreme opposite"[22] was the answer, using conspicuous shapes and violent colour contrasts to confuse enemy submarine commanders.

[22] That dazzle did indeed work along these lines is suggested by the testimony of a U-boat captain:[1] It was not until she was within half a mile that I could make out she was one ship [not several] steering a course at right angles, crossing from starboard to port.

However, the speeds required for motion dazzle are much larger than were available to First World War ships: Scott-Samuel notes that the targets in the experiment would correspond to a dazzle-patterned Land Rover vehicle at a range of 70 m (77 yd), travelling at 90 km/h (56 mph).

It was applied in various ways to British warships such as HMS Implacable, where officers noted approvingly that the pattern "increased difficulty of accurate range finding".

However, following Churchill's departure from the Admiralty, the Royal Navy reverted to plain grey paint schemes,[9] informing Kerr in July 1915 that "various trials had been undertaken and that the range of conditions of light and surroundings rendered it necessary to modify considerably any theory based upon the analogy of [the colours and patterns of] animals".

At sea in 1917, heavy losses of merchant ships to Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare campaign led to new desire for camouflage.

The marine painter Norman Wilkinson promoted a system of stripes and broken lines "to distort the external shape by violent colour contrasts" and confuse the enemy about the speed and dimensions of a ship.

[26] Wilkinson, then a lieutenant commander on Royal Navy patrol duty, implemented the precursor of "dazzle" beginning with the merchantman SS Industry.

[28] Wilkinson's dazzle camouflage was accepted by the Admiralty, even without practical visual assessment protocols for improving performance by modifying designs and colours.

[17] In the First World War, experiments were conducted on British aircraft such as the Royal Flying Corps' Sopwith Camels to make their angle and direction difficult to judge for an enemy gunner.

[39] Dazzle patterns were tested on small model ships at the Royal Navy's Directorate of Camouflage in Leamington Spa; these were painted and then viewed in a shallow tank on the building's roof.

[37][40] The United States Navy implemented a camouflage painting program in World War II, and applied it to many ship classes, from patrol craft and auxiliaries to battleships and some Essex-class aircraft carriers.

[38] Not all United States Navy measures involved dazzle patterns; some were simple or even totally unsophisticated, such as a false bow wave on traditional Haze Gray, or Deck Blue replacing grey over part or all of the ship (the latter to counter the kamikaze threat).

For concealment purposes, the United States Navy littoral combat ship USS Freedom used the "Measure 32" paint scheme during a deployment to Singapore in 2013.

[54] The historian of camouflage Peter Forbes comments that the ships had a Modernist look, their designs succeeding as avant-garde or Vorticist art.

[61][62] Peter Blake was commissioned to design exterior paintwork for MV Snowdrop, a Mersey Ferry, which he called "Everybody Razzle Dazzle", combining his trademark motifs (stars, targets etc.)

[63] In civilian life, patterns reminiscent of dazzle camouflage are sometimes used to mask a test car during trials, to make determining its exterior design difficult.

[64] During the 2015 Formula 1 testing period, the Red Bull RB11 car was painted in a scheme intended to confound rival teams' ability to analyse its aerodynamics.