RMS Olympic

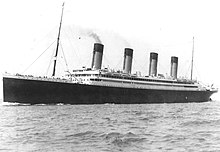

Olympic was the largest ocean liner in the world for two periods during 1910–13, interrupted only by the brief tenure of the slightly larger Titanic, which had the same dimensions but higher gross register tonnage, before the German SS Imperator went into service in June 1913.

Olympic also held the title of the largest British-built liner until RMS Queen Mary was launched in 1934, interrupted only by the short careers of Titanic and Britannic.

[10] Ismay preferred to compete on size and economics rather than speed and proposed to commission a new class of liners that would be bigger than anything that had gone before as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury.

It was overseen by Lord Pirrie, a director of both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line; naval architect Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff's design department; Edward Wilding, Andrews' deputy and responsible for calculating the ship's design, stability and trim; and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard's chief draughtsman and general manager.

Cosmetic differences also existed between the two ships, most noticeably concerning the wider use of Axminster carpeting in Titanic's public rooms, as opposed to the more durable linoleum flooring on Olympic.

After spending a day in Liverpool, open to the public, Olympic sailed to Southampton, where she arrived on 3 June, to be made ready for her maiden voyage.

[44] Designer Thomas Andrews was present for the passage to New York and return, along with a number of engineers with Bruce Ismay and Harland and Wolff's "Guarantee Group" who were also aboard for them to spot any problems or areas for improvement.

[46] As the largest ship in the world, and the first in a new class of superliners, Olympic's maiden voyage attracted considerable worldwide attention from the press and public.

[55][56] At the subsequent inquiry the Royal Navy blamed Olympic for the incident, alleging that her large displacement generated a suction that pulled Hawke into her side.

[62] By 20 November 1911 Olympic was back in service, but, on 24 February 1912, suffered another setback when she lost a propeller blade on an eastbound voyage from New York, and once again returned to her builder for repairs.

[66] When Olympic was about 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) away from Titanic's last known position, she received a message from Captain Rostron of Cunard's RMS Carpathia, which had arrived at the scene.

[71] On 9 October 1912, White Star withdrew Olympic from service and returned her to her builders at Belfast to have modifications added to incorporate lessons learned from the Titanic disaster six months prior, and improve safety.

In addition, an extra bulkhead was added to subdivide the electrical dynamo room, bringing the total number of watertight compartments to seventeen.

[81][82] At the same time, Olympic's B Deck underwent a refit, which included extra cabins in place of the covered promenade, more private bathing facilities, an enlarged Á La Carte restaurant, and a Café Parisien (another addition that had proved popular on Titanic) was added, offering another dining option to first class passengers.

As a wartime measure, Olympic was painted in a grey colour scheme, portholes were blocked, and lights on deck were turned off to make the ship less visible.

By mid-October, bookings had fallen sharply as the threat from German U-boats became increasingly serious, and White Star Line decided to withdraw Olympic from commercial service.

[88][87] On the sixth day of her voyage, 27 October, as Olympic passed near Lough Swilly off the north coast of Ireland, she received distress signals from the battleship HMS Audacious, which had struck a mine off Tory Island and was taking on water.

[90] Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander of the Home Fleet, was anxious to suppress the news of the sinking of Audacious, for fear of the demoralising effect it could have on the British public, so he ordered Olympic to be held in custody at Lough Swilly.

[91] Following Olympic's return to Britain, the White Star Line intended to lay her up in Belfast until the war was over, but in May 1915 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty, to be used as a troop transport, along with the Cunard liners Mauretania and Aquitania.

The Admiralty had initially been reluctant to use large ocean liners as troop transports because of their vulnerability to enemy attack; however, a shortage of ships gave them little choice.

On 24 September 1915 the newly designated HMT (Hired Military Transport) 2810,[93] now under the command of Bertram Fox Hayes, left Liverpool carrying 6,000 soldiers to Moudros, Greece for the Gallipoli Campaign.

On 1 October lifeboats from the French ship Provincia which had been sunk by a U-boat that morning off Cape Matapan were sighted and 34 survivors rescued by Olympic.

However, on investigation it was decided that the ship was unsuitable for this role, because the coal bunkers, which had been designed for transatlantic runs, lacked the capacity for such a long journey at a reasonable speed.

[97] In the early hours of 12 May 1918, while en route for France in the English Channel with U.S. troops under the command of Captain Hayes, Olympic sighted a surfaced U-boat 500 m (1,600 ft) ahead.

[109] Olympic emerged from refit with an increased tonnage of 46,439, allowing her to retain her claim to the title of largest British-built liner afloat, although the Cunard Line's Aquitania was slightly longer.

With the loss of the Titanic and Britannic, Olympic initially lacked any suitable running mates for the express service; however, in 1922 White Star obtained two former German liners, Majestic and Homeric, which had been given to Britain as war reparations.

[113] According to his autobiography,[114] and confirmed by US Immigration records, Cary Grant, then 16-year-old Archibald Leach, first set sail to New York on Olympic on 21 July 1920 on the same voyage on which Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were celebrating their honeymoon.

As Olympic was reversing from her berth at New York harbour, her stern collided with the smaller liner Fort St George, which had crossed into her path.

When completed, these two new ships would handle Cunard White Star's express service; so their fleet of older liners became redundant and were gradually retired.

[133] After being laid up for five months alongside her former rival Mauretania, she was sold to Sir John Jarvis – Member of Parliament – for £97,500, to be partially demolished at Jarrow to provide work for the depressed region.