De-Stalinization

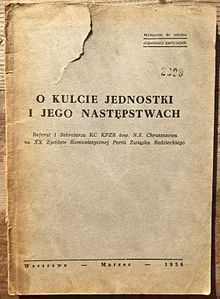

De-Stalinization (Russian: десталинизация, romanized: destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension of Nikita Khrushchev to power,[1] and his 1956 secret speech "On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences", which denounced Stalin's cult of personality and the Stalinist political system.

These reforms were started by the collective leadership which succeeded him after his death on 5 March 1953, comprising Georgi Malenkov, Premier of the Soviet Union; Lavrentiy Beria, head of the Ministry of the Interior; and Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

The term de-Stalinization is one which gained currency in both Russia and the Western world following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but was never used during the Khrushchev era.

[2] However, prior to Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" to the 20th Party Congress, no direct association between Stalin as a person and "the cult of personality" was openly made by Khrushchev or others within the party, although archival documents show that strong criticism of Stalin and his ideology featured in private discussions by Khruschchev at the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet.

[4] This period saw a number of non-publicized political rehabilitations,[5] by way of persons and groups such as Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Politburo members Robert Eikhe and Jānis Rudzutaks, those executed in the Leningrad Affair,[6] and the release of "Article 58ers".

In March 1954, he called for the rehabilitation of the poet Yeghishe Charents, a victim of the Purges, in a speech in Yerevan in his native Armenia.

[1] Khrushchev shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's dictatorial rule and his cult of personality as inconsistent with communist and Party ideology.

Khrushchev argued that if the Party were to be an efficient mechanism, stripped from the brutal abuse of power by any individual, it could transform the Soviet Union as well as the entire world.

[12] On the other hand, historian A. M. Amzad argues that the speech was "deliberate" and "was designed to determine Khrushchev's political fate", as, according to him, necessary initiatives were already taken "to resolve the ills of Stalin's dictatorship".

In November 1961, the large Stalin Statue on Berlin's monumental Stalinallee (promptly renamed Karl-Marx-Allee) was removed in a clandestine operation.

Two climactic acts of de-Stalinization marked the meetings: first, on 31 October 1961, Stalin's body was moved from Lenin's Mausoleum in Red Square to the Kremlin Wall Necropolis;[22] second, on 11 November 1961, the "hero city" Stalingrad was renamed Volgograd.

[24] Khrushchev's biggest contribution to foreign policy is taking advantage of other aspects of de-Stalinisation to try to show the world a different Soviet Union more in line with traditional socialist ideals in Lenin era.

[25] Contemporary historians regard the beginning of de-Stalinization as a turning point in the history of the Soviet Union that began during the Khrushchev Thaw.