de Bruijn sequence

In combinatorial mathematics, a de Bruijn sequence of order n on a size-k alphabet A is a cyclic sequence in which every possible length-n string on A occurs exactly once as a substring (i.e., as a contiguous subsequence).

And since B(k, n) has exactly kn symbols, de Bruijn sequences are optimally short with respect to the property of containing every string of length n at least once.

The number of distinct de Bruijn sequences B(k, n) is For a binary alphabet this is

The sequences are named after the Dutch mathematician Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn, who wrote about them in 1946.

[1] As he later wrote,[2] the existence of de Bruijn sequences for each order together with the above properties were first proved, for the case of alphabets with two elements, by Camille Flye Sainte-Marie (1894).

The generalization to larger alphabets is due to Tatyana van Aardenne-Ehrenfest and de Bruijn (1951).

The earliest known example of a de Bruijn sequence comes from Sanskrit prosody where, since the work of Pingala, each possible three-syllable pattern of long and short syllables is given a name, such as 'y' for short–long–long and 'm' for long–long–long.

This mnemonic, equivalent to a de Bruijn sequence on binary 3-tuples, is of unknown antiquity, but is at least as old as Charles Philip Brown's 1869 book on Sanskrit prosody that mentions it and considers it "an ancient line, written by Pāṇini".

[3] In 1894, A. de Rivière raised the question in an issue of the French problem journal L'Intermédiaire des Mathématiciens, of the existence of a circular arrangement of zeroes and ones of size

[2] This was largely forgotten, and Martin (1934) proved the existence of such cycles for general alphabet size in place of 2, with an algorithm for constructing them.

for binary sequences, de Bruijn proved the conjecture in 1946, through which the problem became well-known.

[2] Karl Popper independently describes these objects in his The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934), calling them "shortest random-like sequences".

[5] An alternative construction involves concatenating together, in lexicographic order, all the Lyndon words whose length divides n.[6] An inverse Burrows–Wheeler transform can be used to generate the required Lyndon words in lexicographic order.

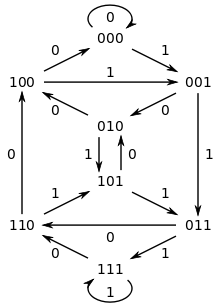

[7] de Bruijn sequences can also be constructed using shift registers[8] or via finite fields.

If one traverses the edge labeled 1 from 000, one arrives at 001, thereby indicating the presence of the subsequence 0001 in the de Bruijn sequence.

Mathematically, an inverse Burrows—Wheeler transform on a word w generates a multi-set of equivalence classes consisting of strings and their rotations.

It can be shown that if we perform the inverse Burrows—Wheeler transform on a word w consisting of the size-k alphabet repeated kn−1 times (so that it will produce a word the same length as the desired de Bruijn sequence), then the result will be the set of all Lyndon words whose length divides n. It follows that arranging these Lyndon words in lexicographic order will yield a de Bruijn sequence B(k,n), and that this will be the first de Bruijn sequence in lexicographic order.

The following method can be used to perform the inverse Burrows—Wheeler transform, using its standard permutation: For example, to construct the smallest B(2,4) de Bruijn sequence of length 24 = 16, repeat the alphabet (ab) 8 times yielding w=abababababababab.

(Standard Permutation) Then, replacing each number by the corresponding letter in w′ from that column yields: (a)(aaab)(aabb)(ab)(abbb)(b).

These are all of the Lyndon words whose length divides 4, in lexicographic order, so dropping the parentheses gives B(2,4) = aaaabaabbababbbb.

The following Python code calculates a de Bruijn sequence, given k and n, based on an algorithm from Frank Ruskey's Combinatorial Generation.

de Bruijn cycles are of general use in neuroscience and psychology experiments that examine the effect of stimulus order upon neural systems,[11] and can be specially crafted for use with functional magnetic resonance imaging.

A de Bruijn sequence can be used to quickly find the index of the least significant set bit ("right-most 1") or the most significant set bit ("left-most 1") in a word using bitwise operations and multiplication.

A de Bruijn torus is a toroidal array with the property that every k-ary m-by-n matrix occurs exactly once.

decoding algorithms exist for special, recursively constructed sequences[17] and extend to the two-dimensional case.

[18] de Bruijn decoding is of interest, e.g., in cases where large sequences or tori are used for positional encoding.

The camera identifies a 6×6 matrix of dots, each displaced from the blue grid (not printed) in one of 4 directions.

The combinations of relative displacements of a 6-bit de Bruijn sequence between the columns, and between the rows gives its absolute position on the digital paper.