De Morgan's laws

In propositional logic and Boolean algebra, De Morgan's laws,[1][2][3] also known as De Morgan's theorem,[4] are a pair of transformation rules that are both valid rules of inference.

They are named after Augustus De Morgan, a 19th-century British mathematician.

The rules allow the expression of conjunctions and disjunctions purely in terms of each other via negation.

Applications of the rules include simplification of logical expressions in computer programs and digital circuit designs.

De Morgan's laws are an example of a more general concept of mathematical duality.

and expressed as truth-functional tautologies or theorems of propositional logic: where

The generalized De Morgan's laws provide an equivalence for negating a conjunction or disjunction involving multiple terms.For a set of propositions

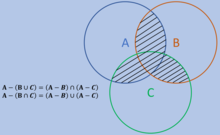

In set theory, it is often stated as "union and intersection interchange under complementation",[5] which can be formally expressed as: where: The generalized form is where I is some, possibly countably or uncountably infinite, indexing set.

In set notation, De Morgan's laws can be remembered using the mnemonic "break the line, change the sign".

[6] In Boolean algebra, similarly, this law which can be formally expressed as: where: which can be generalized to In electrical and computer engineering, De Morgan's laws are commonly written as: and where: De Morgan's laws commonly apply to text searching using Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT.

A similar evaluation can be applied to show that the following two searches will both return Documents 1, 2, and 4: The laws are named after Augustus De Morgan (1806–1871),[7] who introduced a formal version of the laws to classical propositional logic.

De Morgan's formulation was influenced by the algebraization of logic undertaken by George Boole, which later cemented De Morgan's claim to the find.

Nevertheless, a similar observation was made by Aristotle, and was known to Greek and Medieval logicians.

[8] For example, in the 14th century, William of Ockham wrote down the words that would result by reading the laws out.

De Morgan's laws can be proved easily, and may even seem trivial.

[11] Nonetheless, these laws are helpful in making valid inferences in proofs and deductive arguments.

The negation of said disjunction must thus be true, and the result is identical to the first claim.

Working in the opposite direction again, the second expression asserts that at least one of "not A" and "not B" must be true, or equivalently that at least one of A and B must be false.

to denote the complement of A, as above in § Set theory and Boolean algebra.

In extensions of classical propositional logic, the duality still holds (that is, to any logical operator one can always find its dual), since in the presence of the identities governing negation, one may always introduce an operator that is the De Morgan dual of another.

This leads to an important property of logics based on classical logic, namely the existence of negation normal forms: any formula is equivalent to another formula where negations only occur applied to the non-logical atoms of the formula.

The existence of negation normal forms drives many applications, for example in digital circuit design, where it is used to manipulate the types of logic gates, and in formal logic, where it is needed to find the conjunctive normal form and disjunctive normal form of a formula.

Computer programmers use them to simplify or properly negate complicated logical conditions.

Then, the quantifier dualities can be extended further to modal logic, relating the box ("necessarily") and diamond ("possibly") operators: In its application to the alethic modalities of possibility and necessity, Aristotle observed this case, and in the case of normal modal logic, the relationship of these modal operators to the quantification can be understood by setting up models using Kripke semantics.

Three out of the four implications of de Morgan's laws hold in intuitionistic logic.

Specifically, we have and The converse of the last implication does not hold in pure intuitionistic logic.

For a refined version of the failing law concerning existential statements, see the lesser limited principle of omniscience

The validity of the other three De Morgan's laws remains true if negation

for some arbitrary constant predicate C, meaning that the above laws are still true in minimal logic.

Similarly to the above, the quantifier laws: and are tautologies even in minimal logic with negation replaced with implying a fixed