Liber physiognomiae

Scot refers to this as a "doctrine of salvation" (Phisionomia est doctrina salutis), as it easily allows one to determine if a person is virtuous or evil.

[14] The second section begins to focus specifically on physiognomy, considering different organs and body regions that index the "character and faculties" of individuals.

[11][12][15] Early chapters in this portion of the book are written in a medical style, and they detail signs in regards to "temperate and healthy bod[ies] ... repletion of bad humours and excess of blood, cholera, phlegm, and melancholy", before turning to particular sections of the body.

"[18] According to the physiognomy scholar Martin Porter, the Liber physiognomiae is a "distinctly Aristotelian" compendium of "the more Arabic influenced 'medical' aspects of natural philosophy.

[nb 5] The historian Charles Homer Haskins argues that the Liber physiognomiae also "makes free use" of Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (also known as Rhazes) and shows "some affinities" with Trotula texts and writers of the Schola Medica Salernitana (a medical school located in the Italian town of Salerno).

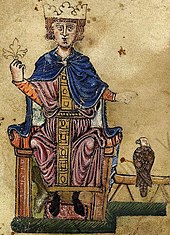

The scholar James Wood Brown argues that the book was likely written for the soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in AD 1209 on the occasion of his wedding to Constance of Aragon.

"[26] The philosophy and religion scholar Irven Resnick argues that the work was given to Frederick so that "the emperor [might be able] to distinguish, from outward appearances, trustworthy and wise counselors from their opposite numbers.

[33] Finally, in 1515 a compendium titled Phisionomia Aristotellis, cum commanto Micaelis Scoti was published, which featured the Liber physiognomiae of Scot, alongside physiognomical works by Aristotle and Bartolomeo della Rocca.

[35] Given the popularity of the Liber physiognomiae, Scot's new formulations and ideas, according to Porter, "introduce[d] some fundamental changes into the structure and nature of the physiognomical aphorism.

"[36] (Effectively, what Scot did was add new meanings to various physical features, making the physiognomical signs discussed in the Liber physiognomiae more complex and, as Porter writes, "polyvalent.

")[35] Second, Scot developed a "stronger conceptual link between physiognomy, issues of hereditary, embryology, and generation, which he articulated through astrological ideas of conception.

According to Porter, this "totalization" of physiognomy—that is, connecting it to a variety of subjects like reproduction and sense perception—was the most dramatic change that occurred in the way that physiognomy was practiced "as it developed in the period between classical Athens and late fifteenth-century Europe".