Aristotle's biology

Aristotle's method, too, resembled the style of science used by modern biologists when exploring a new area, with systematic data collection, discovery of patterns, and inference of possible causal explanations from these.

Apart from his pupil, Theophrastus, who wrote a matching Enquiry into Plants, no research of comparable scope was carried out in ancient Greece, though Hellenistic medicine in Egypt continued Aristotle's inquiry into the mechanisms of the human body.

Translation of Arabic versions and commentaries into Latin brought knowledge of Aristotle back into Western Europe, but the only biological work widely taught in medieval universities was On the Soul.

The association of his work with medieval scholasticism, as well as errors in his theories, caused Early Modern scientists such as Galileo and William Harvey to reject Aristotle.

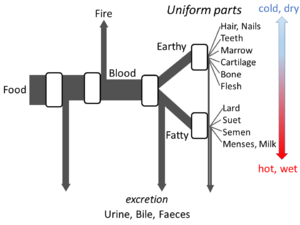

The incoming material, food, enters the body and is concocted into blood; waste is excreted as urine, bile, and faeces, and the element fire is released as heat.

[11][12] All the tissues are in Aristotle's view completely uniform parts with no internal structure of any kind; a cartilage for example was the same all the way through, not subdivided into atoms as Democritus (c. 460–c.

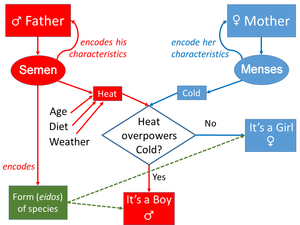

The child's sex can be influenced by factors that affect temperature, including the weather, the wind direction, diet, and the father's age.

Aristotle argues instead that the process has a predefined goal: that the "seed" that develops into the embryo began with an inbuilt "potential" to become specific body parts, such as vertebrae.

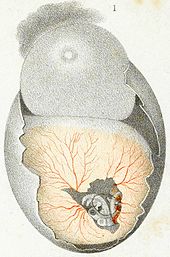

[26] He used the ancient Greek term pepeiramenoi to mean observations, or at most investigative procedures,[27] such as (in Generation of Animals) finding a fertilised hen's egg of a suitable stage and opening it so as to be able to see the embryo's heart inside.

[28] Instead, he practised a different style of science: systematically gathering data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these.

[24] From the data he collected and documented, Aristotle inferred quite a number of rules relating the life-history features of the live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals[j]) that he studied.

[23] The French playwright Molière's 1673 play The Imaginary Invalid portrays the quack Aristotelian doctor Argan blandly explaining that opium causes sleep by virtue of its dormitive [sleep-making] principle, its virtus dormitiva.

Further, he provided mechanical, non-vitalist analogies for these theories, mentioning bellows, toy carts, the movement of water through porous pots, and even automatic puppets.

[1][33] His data are assembled from his own observations, statements given by people with specialised knowledge such as beekeepers and fishermen, and less accurate accounts provided by travellers from overseas.

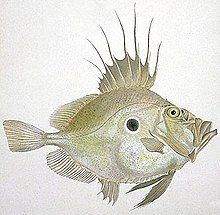

He separated the aquatic mammals from fish, and knew that sharks and rays were part of the group he called Selachē (roughly, the modern zoologist's selachians[l]).

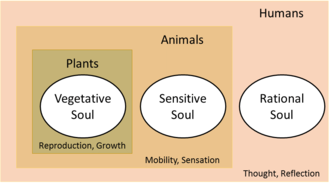

[m][47][48] Animals with blood included live-bearing tetrapods, Zōiotoka tetrapoda (roughly, the mammals), being warm, having four legs, and giving birth to their young.

The cetaceans, Kētōdē, also had blood and gave birth to live young, but did not have legs, and therefore formed a separate group[n] (megista genē, defined by a set of functioning "parts"[49]).

The highest animals gave birth to warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs.

These are arranged from the most energetic to the least, so the warm, wet young raised in a womb with a placenta were higher on the scale than the cold, dry, nearly mineral eggs of birds.

[58] Where Aristotle insisted that species have a fixed place on the scala naturae, Theophrastus suggests that one kind of plant can transform into another, as when a field sown to wheat turns to the weed darnel.

The first medical teacher at Alexandria, Herophilus of Chalcedon, corrected Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation.

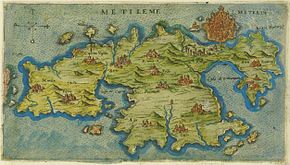

[66] When the Christian Alfonso VI of Castile retook the Kingdom of Toledo from the Moors in 1085, an Arabic translation of Aristotle's works, with commentaries by Avicenna and Averroes emerged into European medieval scholarship.

Edward Wotton similarly helped to found modern zoology by arranging the animals according to Aristotle's theories, separating out folklore from his 1552 De differentiis animalium.

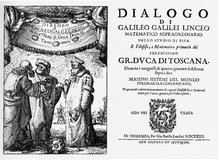

In 1632, Galileo represented Aristotelianism in his Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems) by the strawman Simplicio ("Simpleton"[73]).

Leroi noted that in 1985, Peter Medawar stated in "pure seventeenth century"[76] tones that Aristotle had assembled "a strange and generally speaking rather tiresome farrago of hearsay, imperfect observation, wishful thinking and credulity amounting to downright gullibility".

[76][77] Zoologists working in the 19th century, including Georges Cuvier, Johannes Peter Müller,[78] and Louis Agassiz admired Aristotle's biology and investigated some of his observations.

[79][80][81][82] Charles Darwin quoted a passage from Aristotle's Physics II 8 in The Origin of Species, which entertains the possibility of a selection process following the random combination of body parts.

Secondly, according to Leroi, Aristotle was in any case discussing ontogeny, the Empedoclean coming into being of an individual from component parts, not phylogeny and natural selection.

However, modern observation has confirmed one after another of his more surprising claims,[68] including the active camouflage of the octopus[87] and the ability of elephants to snorkel with their trunks while swimming.

[r][90] Few practicing zoologists explicitly adhere to Aristotle's great chain of being, but its influence is still perceptible in the use of the terms "lower" and "upper" to designate taxa such as groups of plants.