Deadweight loss

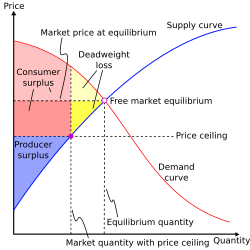

Deadweight loss can also be a measure of lost economic efficiency when the socially optimal quantity of a good or a service is not produced.

If market conditions are perfect competition, producers would charge a price of $0.10, and every customer whose marginal benefit exceeds $0.10 would buy a nail.

A monopoly producer of this product would typically charge whatever price will yield the greatest profit for themselves, regardless of lost efficiency for the economy as a whole.

In this example, the monopoly producer charges $0.60 per nail, thus excluding every customer from the market with a marginal benefit less than $0.60.

The difference between the cost of production and the purchase price then creates the "deadweight loss" to society.

Whereas a subsidy entices consumers to buy a product that would otherwise be too expensive for them in light of their marginal benefit (price is lowered to artificially increase demand), a tax dissuades consumers from a purchase (price is increased to artificially lower demand).

For example, "sin taxes" levied against alcohol and tobacco are intended to artificially lower demand for these goods; some would-be users are priced out of the market, i.e. total smoking and drinking are reduced.

Indirect taxes are usually paid by large entities such as corporations or manufacturers but are partially shifted towards the consumer.

It also refers to the deadweight loss created by a government's failure to intervene in a market with externalities.

[3] The area represented by the triangle results from the fact that the intersection of the supply and the demand curves are cut short.

Some economists like Martin Feldstein maintain that these triangles can seriously affect long-term economic trends by pivoting the trend downwards and causing a magnification of losses in the long run but others like James Tobin have argued that they do not have a huge impact on the economy.

The Hicksian (per John Hicks) and the Marshallian (per Alfred Marshall) demand function differ about deadweight loss.

However, Hicks analyzed the situation through indifference curves and noted that when the Marshallian demand curve is perfectly inelastic, the policy or economic situation that caused a distortion in relative prices has a substitution effect, i.e. is a deadweight loss.

The difference is attributable to the behavioral changes induced by a distortionary tax that are measured by the substitution effect.

However, that is not the only interpretation, and Pigou did not use a lump sum tax as the point of reference to discuss deadweight loss (excess burden).

However, if the government were to decide to impose a $50 tax upon the providers of cleaning services, their trade would no longer benefit them.

They have thus lost amount of the surplus that they would have received from their deal, and at the same time, this made each of them worse off to the tune of $40 in value.

Taxes cause deadweight losses because they prevent buyers and sellers from realizing some of the gains from trade.

[5] Price elasticities of supply and demand determine whether the deadweight loss from a tax is large or small.

Imposing this effective tax distorts the market outcome, and the wedge causes a decrease in the quantity sold, below the social optimum.

It is important to remember the difference between the two cases: whereas the government receives the revenue from a genuine tax, monopoly profits are collected by a private firm.