GNU Hurd

When the Linux kernel proved to be a viable solution, development of GNU Hurd slowed, at times alternating between stasis and renewed activity and interest.

[5] The Hurd's design consists of a set of protocols and server processes (or daemons, in Unix terminology) that run on the GNU Mach microkernel.

[4] The Hurd aims to surpass the Unix kernel in functionality, security, and stability, while remaining largely compatible with it.

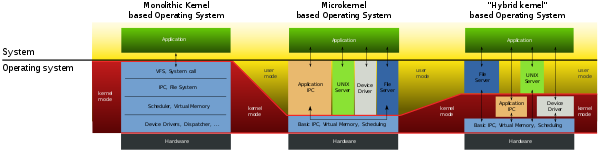

The GNU Project chose the multiserver microkernel[6] for the operating system, due to perceived advantages over the traditional Unix monolithic kernel architecture,[7] a view that had been advocated by some developers in the 1980s.

The logo is a graph where nodes represent the Hurd kernel's servers and directed edges are IPC messages.

[10] Initially the components required for kernel development were written: editors, shell, compiler, debugger etc.

[13] According to Thomas Bushnell, the initial Hurd architect, their early plan was to adapt the 4.4BSD-Lite kernel and, in hindsight, "It is now perfectly obvious to me that this would have succeeded splendidly and the world would be a very different place today.

Work on this was delayed for three years due to uncertainty over whether CMU would release the Mach code under a suitable license.

Despite an optimistic announcement by Stallman in 2002 predicting a release of GNU/Hurd later that year,[15] the Hurd is still not considered suitable for production environments.

It makes some progress, but to be really superior it would require solving a lot of deep problems", but added that "finishing it is not crucial" for the GNU system because a free kernel already existed (Linux), and completing Hurd would not address the main remaining problem for a free operating system: device support.

[20] Unlike most Unix-like kernels, the Hurd uses a server–client architecture, built on a microkernel that is responsible for providing the most basic kernel services – coordinating access to the hardware: the CPU (through process management and scheduling), RAM (via memory management), and other various input/output devices (via I/O scheduling) for sound, graphics, mass storage, etc.

This was a technical decision made by Richard Stallman, who thought it would speed up the work by saving a large part of it.

[28] In 2008, Neal Walfield began working on the Viengoos microkernel as a modern native kernel for HURD.