Debye model

The Debye model correctly predicts the low-temperature dependence of the heat capacity of solids, which is proportional to

[clarification needed] The Debye model treats atomic vibrations as phonons confined in the solid's volume.

Most of the calculation steps are identical, as both are examples of a massless Bose gas with a linear dispersion relation.

, the resonating modes of the sonic disturbances (considering for now only those aligned with one axis), treated as particles in a box, have wavelengths given as where

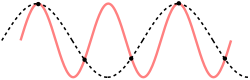

The following illustration describes transverse phonons in a cubic solid at varying frequencies:

It is reasonable to assume that the minimum wavelength of a phonon is twice the atomic separation, as shown in the lowest example.

Phonons obey Bose–Einstein statistics, and their distribution is given by the Bose–Einstein statistics formula: Because a phonon has three possible polarization states (one longitudinal, and two transverse, which approximately do not affect its energy) the formula above must be multiplied by 3, Considering all three polarization states together also means that an effective sonic velocity

, where longitudinal and transversal sound-wave velocities are averaged, weighted by the number of polarization states.

As the energy function does not depend on either of the angles, the equation can be simplified to The number of particles in the original cube and in the eighth of a sphere should be equivalent.

The more elementary formulae given further down give the asymptotic behavior in the limit of low and high temperatures.

Using continuum mechanics, he found that the number of vibrational states with a frequency less than a particular value was asymptotic to in which

chosen so that the total number of states is Debye knew that this assumption was not really correct (the higher frequencies are more closely spaced than assumed), but it guarantees the proper behaviour at high temperature (the Dulong–Petit law).

First the vibrational frequency distribution is derived from Appendix VI of Terrell L. Hill's An Introduction to Statistical Mechanics.

[5] Consider a three-dimensional isotropic elastic solid with N atoms in the shape of a rectangular parallelepiped with side-lengths

), From above, we can get an expression for 1/A; substituting it into (6), Integrating with respect to ν yields The temperature of a Debye solid is said to be low if

, leading to This definite integral can be evaluated exactly: In the low-temperature limit, the limitations of the Debye model mentioned above do not apply, and it gives a correct relationship between (phononic) heat capacity, temperature, the elastic coefficients, and the volume per atom (the latter quantities being contained in the Debye temperature).

leads to which upon integration gives This is the Dulong–Petit law, and is fairly accurate although it does not take into account anharmonicity, which causes the heat capacity to rise further.

The total heat capacity of the solid, if it is a conductor or semiconductor, may also contain a non-negligible contribution from the electrons.

Even though the Debye model is not completely correct, it gives a good approximation for the low temperature heat capacity of insulating, crystalline solids where other contributions (such as highly mobile conduction electrons) are negligible.

) is a parameter in the Debye model that refers to a cut-off angular frequency for waves of a harmonic chain of masses, used to describe the movement of ions in a crystal lattice and more specifically, to correctly predict that the heat capacity in such crystals is constant at high temperatures (Dulong–Petit law).

The speed of sound in the crystal depends on the mass of the atoms, the strength of their interaction, the pressure on the system, and the polarisation of the spin wave (longitudinal or transverse), among others.

[16] The assumed dispersion relation is easily proven inaccurate for a one-dimensional chain of masses, but in Debye's model, this does not prove to be problematic.

In Debye's derivation of the heat capacity, he sums over all possible modes of the system, accounting for different directions and polarisations.

The sum runs over all modes without differentiating between different polarizations, and then counts the total number of polarization-mode combinations.

is the size of the system; and the integral is (as the summation) over all possible modes, which is assumed to be a finite region (bounded by the cut-off frequency).

The summation over the modes is rewritten The result is Thus the Debye frequency is found The calculated effective velocity

In classical mechanics, it is known that for an equidistant chain of masses which interact harmonically with each other, the dispersion relation is[16]

After plotting this relation, Debye's estimation of the cut-off wavelength based on the linear assumption remains accurate, because for every wavenumber bigger than

For a one-dimensional chain, the formula for the Debye frequency can also be reproduced using a theorem for describing aliasing.

The Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem is used for this derivation, the main difference being that in the case of a one-dimensional chain, the discretization is not in time, but in space.