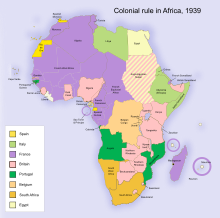

Decolonisation of Africa

Colonial governments gave way to sovereign states in a process often marred by violence, political turmoil, widespread unrest, and organised revolts.

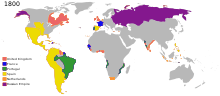

The end of the First World War saw the breakup of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires according to the principles espoused in Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points.

Though many anti-colonial intellectuals saw the potential of Wilsonianism to advance their aims, Wilson had no intention of applying the principle of self-determination outside the lands of the defeated Central Powers.

Many Africans were compelled or even forced into military service by their respective colonial regimes, but some voluntarily enlisted in search of better opportunities than they could find in civilian employment.

[16] On 12 February 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss the post-war world.

Prime Minister Churchill argued in the British Parliament that the document referred to "the States and nations of Europe now under the Nazi yoke".

[22] In 1948, three years after the end of World war II, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognised all people as being born free and equal.

[26] Colonial economic exploitation involved diverting resource extraction (such as mining) profits to European shareholders at the expense of internal development, causing significant local socioeconomic grievances.

[28][29] In the 1930s, the colonial powers had cultivated, sometimes inadvertently, a small elite of local African leaders educated in Western universities, where they became familiar with ideas such as self-determination.

Although independence was not encouraged, arrangements between these leaders and the colonial powers developed,[11] and such figures as Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Kwame Nkrumah (Gold Coast, now Ghana), Julius Nyerere (Tanganyika, now Tanzania), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal), Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria), Patrice Lumumba (DRC) and Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) came to lead the struggles for African nationalism.

During the Second World War, some local African industries and towns expanded when U-boats patrolling the Atlantic Ocean impeded the shipping of raw materials to Europe.

[12][better source needed] Over time, urban communities, industries, and trade unions grew, improving literacy and education, and leading to the establishment of pro-independence newspapers.

[12][better source needed] By 1945, the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism, and delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya and Malawi among other nationalist activists.

[30] Following World War II, rapid decolonisation swept across the continent of Africa as many territories gained their independence from European colonisation.

In August 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss their post-war goals.

[citation needed] Historian James Meriweather argues that American policy towards Africa was characterized by a middle road approach, which supported African independence but also reassured European colonial powers that their holdings would remain intact.

Washington wanted the right type of African groups to lead newly independent states, in other words communist and not especially democratic.

[41] Starting with the 1945 Pan-African Congress, the Gold Coast's (modern-day Ghana's) independence leader Kwame Nkrumah made his focus clear.

After being released from prison, Nkrumah founded the Convention People's Party (CPP), which launched a wide-scale campaign in support of independence with the slogan "Self Government Now!

In 1956, Ghana requested independence inside the Commonwealth, which was granted peacefully in 1957 with Nkrumah as prime minister and Queen Elizabeth II as sovereign.

Control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle, who used the colonial bases as a launching point to help expel the Vichy government from Metropolitan France.

The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control.

However, Independence was explicitly rejected as a future possibility: After the war ended, France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement.

The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.

They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence, on one hand, he was creating new ties with the help of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters.

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements.

While some European colonisation focused on shorter-term exploitation of economic opportunities (Newfoundland, for example, or Siberia) or addressed specific goals such as settlers seeking religious freedom (Massachusetts), at other times long-term social and economic planning was involved for both parties, but more on the colonizing countries themselves, based on elaborate theory-building (note James Oglethorpe's Colony of Georgia in the 1730s and Edward Gibbon Wakefield's New Zealand Company in the 1840s).

[72] Despite this continued reliance and unfair trading terms, a meta-analysis of 18 African countries found that a third of them experienced increased economic growth post-independence.

[full citation needed] Language has been used by western colonial powers to divide territories and create new identities, which have led to conflicts and tensions between African nations.