Deep Space 1

Launched on 24 October 1998, the Deep Space 1 spacecraft carried out a flyby of asteroid 9969 Braille, which was its primary science target.

Thus a spacecraft can determine its relative position by tracking such asteroids across the star background, which appears fixed over such timescales.

Existing spacecraft are tracked by their interactions with the transmitters of the NASA Deep Space Network (DSN), in effect an inverse GPS.

After initial acquisition, Autonav keeps the subject in frame, even commandeering the spacecraft's attitude control.

[6] ABLE Engineering developed the concentrator technology and built the solar array for DS1, with Entech Inc, who supplied the Fresnel optics, and the NASA Glenn Research Center.

The activity was sponsored by the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, developed originally for the SSI - Conestoga 1620 payload, METEOR.

This lack of a performance history in space meant that despite the potential savings in propellant mass, the technology was considered too experimental to be used for high-cost missions.

Furthermore, unforeseen side effects of ion propulsion might in some way interfere with typical scientific experiments, such as fields and particle measurements.

This is an order of magnitude higher than traditional space propulsion methods, resulting in a mass savings of approximately half.

[9] Remote Agent successfully demonstrated the ability to plan onboard activities and correctly diagnose and respond to simulated faults in spacecraft components through its built-in REPL environment.

[10] Autonomous control will enable future spacecraft to operate at greater distances from Earth and to carry out more sophisticated science-gathering activities in deep space.

The MICAS (Miniature Integrated Camera And Spectrometer) instrument combined visible light imaging with infrared and ultraviolet spectroscopy to determine chemical composition.

Early in the mission, material ejected during launch vehicle separation caused the closely spaced ion extraction grids to short-circuit.

The contamination was eventually cleared, as the material was eroded by electrical arcing, sublimed by outgassing, or simply allowed to drift out.

[17] It was thought that the ion engine exhaust might interfere with other spacecraft systems, such as radio communications or the science instruments.

Although MICAS is more sensitive, its field-of-view is an order of magnitude smaller, creating a greater information processing burden.

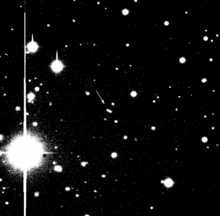

Due to technical difficulties, including a software crash shortly before approach, the craft instead passed Braille at a distance of 26 km (16 mi).

This, plus Braille's lower albedo, meant that the asteroid was not bright enough for the Autonav to focus the camera in the right direction, and the picture shoot was delayed by almost an hour.

Deep Space 1 then entered its second extended mission phase, focused on retesting the spacecraft's hardware technologies.

The highly efficient ion thruster had a sufficient amount of propellant left to perform attitude control in addition to main propulsion, thus allowing the mission to continue.

[18] During late October and early November 1999, during the spacecraft's post-Braille encounter coast phase, Deep Space 1 observed Mars with its MICAS instrument.

[13][16] Deep Space 1 succeeded in its primary and secondary objectives, returning valuable science data and images.