Deep operation

The goal of a deep operation was to inflict a decisive strategic defeat on the enemy's logistical abilities and render the defence of their front more difficult, impossible or irrelevant.

[6] Frunze's position eventually found favour with the officer elements that had experienced the poor command and control of Soviet forces in the conflict with Poland during the Polish–Soviet War.

The latter opinion was motivated in part by the condition of the Soviet Union's economy: the country was still not industrialized and thus was economically too weak to fight a long war of attrition.

Tukhachevsky's neglect of defense pushed the Red Army toward the decisive battle and cult of the offensive mentality, which along with other events, caused enormous problems in 1941.

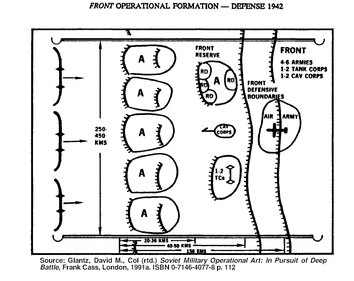

[14] The goal of the defence in depth concept was to blunt the elite enemy forces, which would be first to breach the Soviet lines, several times, causing them to exhaust themselves.

This involves the capability of a commander on "the use of military forces to achieve strategic goals through the design, organization, integration and conduct of theater strategies, campaigns, major operations and battles.

Isserson argued that the front had become devoid of open flanks and military art faced a challenge to develop new methods to break through a deeply echeloned defence.

The holding group would be positioned on either flank of the combat zone to tie down enemy reinforcements via means of diversion attacks or blocking defence.

If that failed, and the enemy succeeded in sweeping aside the holding forces and breaching several of the main defence lines, mobile operational reserves, including tanks and assault aviation, would be committed.

These forces would be allocated to holding and shock groups alike and were often positioned behind the main defences to engage the battle worn enemy thrust.

Although that was the crucial first step, tactical deep battle offered no solution about how a force could sustain an advance beyond it and into the operational and strategic depths of an enemy front.

The success of tactical action counted for little in an operational defensive zone that extended dozens of kilometres and in which the enemy held large reserves.

[21] That was demonstrated during the First World War, when initial breakthroughs were rendered useless by the exhaustion during the tactical effort, limited mobility, and a slow-paced advance and enemy reinforcements.

[22] Triandafillov's successor, Nikolai Efimovich Varfolomeev, was less concerned with developing the quantitative indices of deep battle but rather with the mechanics of the shock army's mission.

[23] Varfolomeev noted that deep and echeloned tactical and operational defences should call for equal or similar counter responses from the attacker.

Triandafillov stated in 1929: The outcome in modern war will be attained not through the physical destruction of the opponent but rather through a succession of developing manoeuvres that will aim at inducing him to see his ability to comply further with his operational goals.

In that sense, the Soviet deep battle, in the words of one historian, "was radically different to the nebulous 'blitzkrieg'" method but produced similar, if more strategically-impressive, results.

However, the death of Triandafillov in an airplane crash and the Great Purge of 1937 to 1939 removed many of the leading officers of the Red Army, including Svechin, Varfolomeev and Tukhachevsky.

The scale of operations may reach mammoth proportions as in the breakthrough of German defenses on the River Oder by some 4,000 tanks supported by 5,000 planes on a 50-mile front.

The Red Army maintained the strategic initiative during the third and final period of war (1944–1945) and ultimately played the central role in the Allied victory in Europe.

Once there and reinforced by airborne or air-landed forces, they ruled the countryside, forests, and swamps but were unable to drive the more mobile Germans from the main communications arteries and villages.

In operational terms, by drawing the German Army into the city of Stalingrad, they denied them the chance to practice their greater experience in mobile warfare.

The Red Army was able to force its enemy to fight in a limited area, hampered by the city landscape, unable to use its mobility or firepower as effectively as in the open country.

When Soviet intelligence had reason to believe the Axis front was at its weakest, it would strike at the flanks and encircle the German Army (Operation Uranus).

The aim of the Soviets was to allow the German army to weaken in the winter conditions and inflict attrition on any attempt by the enemy to relieve the pocket.

The lack of diversionary operations allowed the German Army to recognise the danger, concentrate powerful mobile forces, and dispatch sufficient reserves to Kharkov.

For the first time in the war, at Kursk the Soviets eschewed a preemptive offensive and instead prepared an imposing strategic defense, unparalleled in its size and complexity, in order to crush the advancing Germans.

Moreover, Soviet strategists recognised that Ukraine offered the best route through which to reach Germany's allies, such as Romania, with its oilfields, vital to Axis military operations.

All actions are carried out with the following goals in mind: to retain the initiative, to defeat the pursued enemy in detail, and to surround and destroy his reserves after cutting them off.

This denied the Soviets the opportunity to pin them down in the tactical defence belts and release their operational reserves to engage the enemy on favourable terms.