Deep biosphere

The first indications of deep life came from studies of oil fields in the 1920s, but it was not certain that the organisms were indigenous until methods were developed in the 1980s to prevent contamination from the surface.

Lower down, these are not available, so they make use of "edibles" (electron donors) such as hydrogen (released from rocks by various chemical processes), methane (CH4), reduced sulfur compounds, and ammonium (NH4).

"[8] At the University of Chicago in the 1920s, geologist Edson Bastin enlisted the help of microbiologist Frank Greer in an effort to explain why water extracted from oil fields contained hydrogen sulfide and bicarbonates.

[9][10][11] Also in the 1920s, Charles Lipman, a microbiologist at the University of California, Berkeley, noticed that bacteria that had been sealed in bottles for 40 years could be reanimated – a phenomenon now known as anhydrobiosis.

[15] Most biologists dismissed the subsurface microbes as contamination, especially after the submersible Alvin sank in 1968 and the scientists escaped, leaving their lunches behind.

The study of the deep biosphere, like many bacteria, was dormant for decades; an exception is a group of Soviet microbiologists who began to refer to themselves as geomicrobiologists.

[12] In 1992, Thomas Gold published a paper titled "The Deep, Hot Biosphere" suggesting that microbial life was widespread throughout the subsurface, existing in pore spaces between grains of rocks.

[17] In 1998, William Whitman and colleagues published a summary of twelve years of data in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[18][6] In 2016, International Ocean Discovery Program Leg 370 drilled into the marine sediment of the Nankai Accretionary Prism and observed 102 vegetative cells per cm3 at 118 °C.

[2][19] The present understanding of subsurface biology was made possible by numerous advances in technology for sample collection, field analysis, molecular science, cultivation, imaging and computation.

[31] Methods from modern molecular biology allow the extraction of nucleic acids, lipids and proteins from cells, DNA sequencing, and the physical and chemical analysis of molecules using mass spectrometry and flow cytometry.

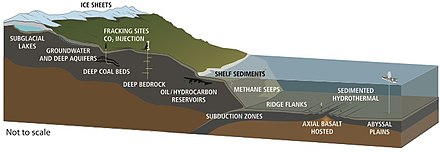

Other processes that might provide habitats for life include roll front development in ore bodies,[note 1] subduction, methane clathrate formation and decomposition, permafrost thawing, infrared radiation and seismic activity.

Over 90% of methane is oxidized by microbes before it reaches the surface; this activity is "one of the most important controls on greenhouse gas emissions and climate on Earth.

This can harm the cells in a variety of ways, and experiments at surface pressures produce an inaccurate picture of microbial activity in the deep biosphere.

[49] High temperatures stress organisms, increasing the rates of processes that damage important molecules such as DNA and amino acids.

[53] Thermochronology data of Precambrian cratons suggest that habitable temperature conditions of the subsurface in these settings range back to about a billion years maximum.

The water carries oxygen, fresh organic matter and dissolved metabolites, resulting in a heterogenous environment with abundant nutrients.

The ocean surface is very poor in nutrients such as nitrate, phosphate and iron, limiting the growth of phytoplankton; this results in low sedimentation rates.

In such environments, cells are mostly either strictly aerobic or facultative anaerobic (using oxygen where available but able to switch to other electron acceptors in its absence[77]) and they are heterotrophic (not primary producers).

Upwelling brings nutrient-rich water to the surface, stimulating abundant growth of phytoplankton, which then settle to the bottom (a phenomenon known as the biological pump).

[44] Mid-ocean ridges are a hot, rapidly changing environment with a steep vertical temperature gradient, so life can only exist in the top few meters.

The subducting plate releases volatiles and solutes to these volcanoes, resulting in acidic fluids with higher concentrations of gases and metals than in the mid-ocean ridge.

When hotspot volcanoes occur in the middle of oceanic plates, they create permeable and porous basalts with higher concentrations of gas than at mid-ocean ridges.

[34] Continents have a complex history and a great variety of rocks, sediments and soils; the climate on the surface, temperature profiles and hydrology also vary.

There is a lot of diversity, although the deepest tend to be iron(III)- or sulfate-reducing bacteria that use fermentation and can thrive in high temperature and salinity.

[78] In 2019 microbial organisms were discovered living 2,400 meters below the surface, breathing sulfur and eating rocks such as pyrite as their regular food source.

[83] Humans have accessed deep aquifers in igneous rocks for a variety of purposes including groundwater extraction, mining, and storage of hazardous wastes.

[84][85] Stable isotope records of (secondary) fracture-lining minerals of the continental igneous rock-hosted deep biosphere point to long-term occurrence of methanogenesis, methanotrophy and sulfate reduction.

Members of the Chloroflexi bacterial phylum draw energy from it to produce acetate by reducing carbon dioxide or organic matter (a process known as acetogenesis).

In the sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ), anaerobic methanotrophic (ANME) archaea form consortia with sulfate-reducing bacteria.