Abyssal plain

Magma rises from above the asthenosphere (a layer of the upper mantle), and as this basaltic material reaches the surface at mid-ocean ridges, it forms new oceanic crust, which is constantly pulled sideways by spreading of the seafloor.

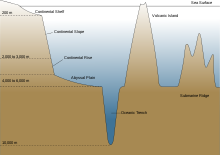

Abyssal plains result from the blanketing of an originally uneven surface of oceanic crust by fine-grained sediments, mainly clay and silt.

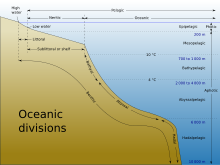

Factors such as climate change, fishing practices, and ocean fertilization have a substantial effect on patterns of primary production in the euphotic zone.

Abyssal plains were not recognized as distinct physiographic features of the sea floor until the late 1940s and, until recently, none had been studied on a systematic basis.

Otherwise, they must rely on material sinking from above,[1] or find another source of energy and nutrition, such as occurs in chemosynthetic archaea found near hydrothermal vents and cold seeps.

[30] These faults pervading the oceanic crust, along with their bounding abyssal hills, are the most common tectonic and topographic features on the surface of the Earth.

The flat appearance of mature abyssal plains results from the blanketing of this originally uneven surface of oceanic crust by fine-grained sediments, mainly clay and silt.

[34][35][36][37] The landmark scientific expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British Royal Navy survey ship HMS Challenger yielded a tremendous amount of bathymetric data, much of which has been confirmed by subsequent researchers.

Bathymetric data obtained during the course of the Challenger expedition enabled scientists to draw maps,[38] which provided a rough outline of certain major submarine terrain features, such as the edge of the continental shelves and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

This discontinuous set of data points was obtained by the simple technique of taking soundings by lowering long lines from the ship to the seabed.

[41] [42] Beginning in 1916, Canadian physicist Robert William Boyle and other scientists of the Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee (ASDIC) undertook research which ultimately led to the development of sonar technology.

Maps produced from these techniques show the major Atlantic basins, but the depth precision of these early instruments was not sufficient to reveal the flat featureless abyssal plains.

Thus, water emerging from the hottest parts of some hydrothermal vents, black smokers and submarine volcanoes can be a supercritical fluid, possessing physical properties between those of a gas and those of a liquid.

This is an area of the seabed where seepage of hydrogen sulfide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluid occurs, often in the form of a deep-sea brine pool.

[54] Though the plains were once assumed to be vast, desert-like habitats, research over the past decade or so shows that they teem with a wide variety of microbial life.

[71] Peracarid crustaceans, including isopods, are known to form a significant part of the macrobenthic community that is responsible for scavenging on large food falls onto the sea floor.

[72] In 2005, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) remotely operated vehicle, KAIKO, collected sediment core from the Challenger Deep.

Out of the 432 organisms collected, the overwhelming majority of the sample consisted of simple, soft-shelled foraminifera, with others representing species of the complex, multi-chambered genera Leptohalysis and Reophax.

Some species live in the coldest ocean temperatures of the hadal zone, while others can be found in the extremely hot waters adjacent to hydrothermal vents.

Although the process of chemosynthesis is entirely microbial, these chemosynthetic microorganisms often support vast ecosystems consisting of complex multicellular organisms through symbiosis.

[83] These communities are characterized by species such as vesicomyid clams, mytilid mussels, limpets, isopods, giant tube worms, soft corals, eelpouts, galatheid crabs, and alvinocarid shrimp.

Abyssal seafloor communities are considered to be food limited because benthic production depends on the input of detrital organic material produced in the euphotic zone, thousands of meters above.

[84] Most of the organic flux arrives as an attenuated rain of small particles (typically, only 0.5–2% of net primary production in the euphotic zone), which decreases inversely with water depth.

[9] The small particle flux can be augmented by the fall of larger carcasses and downslope transport of organic material near continental margins.

Because deep sea fish are long-lived and slow growing, these deep-sea fisheries are not thought to be sustainable in the long term given current management practices.

These potato-sized concretions of manganese, iron, nickel, cobalt, and copper, distributed on the seafloor at depths of greater than 4000 meters,[85] are of significant commercial interest.

[87] The abyssal Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone (CCFZ) is an area within the Pacific nodule province that is currently under exploration for its mineral potential.

[87] Limited knowledge of the taxonomy, biogeography and natural history of deep sea communities prevents accurate assessment of the risk of species extinctions from large-scale mining.

In 2004, the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea (IFREMER) conducted the Nodinaut expedition to this mining track (which is still visible on the seabed) to study the long-term effects of this physical disturbance on the sediment and its benthic fauna.

On the other hand, the biological activity measured in the track by instruments aboard the crewed submersible bathyscaphe Nautile did not differ from a nearby unperturbed site.