Degenerate energy levels

Conversely, two or more different states of a quantum mechanical system are said to be degenerate if they give the same value of energy upon measurement.

It is represented mathematically by the Hamiltonian for the system having more than one linearly independent eigenstate with the same energy eigenvalue.

In classical mechanics, this can be understood in terms of different possible trajectories corresponding to the same energy.

The possible states of a quantum mechanical system may be treated mathematically as abstract vectors in a separable, complex Hilbert space, while the observables may be represented by linear Hermitian operators acting upon them.

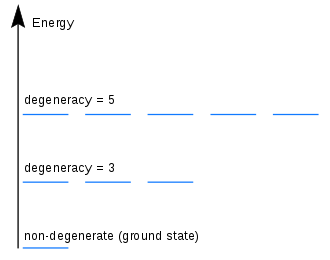

The dimension of the eigenspace corresponding to that eigenvalue is known as its degree of degeneracy, which can be finite or infinite.

The eigenvalues of the matrices representing physical observables in quantum mechanics give the measurable values of these observables while the eigenstates corresponding to these eigenvalues give the possible states in which the system may be found, upon measurement.

This section intends to illustrate the existence of degenerate energy levels in quantum systems studied in different dimensions.

In several cases, analytic results can be obtained more easily in the study of one-dimensional systems.

It can be proven that in one dimension, there are no degenerate bound states for normalizable wave functions.

satisfy the condition given above, it can be shown[3] that also the first derivative of the wave function approaches zero in the limit

Real two-dimensional materials are made of monoatomic layers on the surface of solids.

The presence of degenerate energy levels is studied in the cases of Particle in a box and two-dimensional harmonic oscillator, which act as useful mathematical models for several real world systems.

Degenerate states are also obtained when the sum of squares of quantum numbers corresponding to different energy levels are the same.

For two commuting observables A and B, one can construct an orthonormal basis of the state space with eigenvectors common to the two operators.

These additional labels required naming of a unique energy eigenfunction and are usually related to the constants of motion of the system.

Studying the symmetry of a quantum system can, in some cases, enable us to find the energy levels and degeneracies without solving the Schrödinger equation, hence reducing effort.

The eigenfunctions corresponding to a n-fold degenerate eigenvalue form a basis for a n-dimensional irreducible representation of the Symmetry group of the Hamiltonian.

For a particle moving on a cone under the influence of 1/r and r2 potentials, centred at the tip of the cone, the conserved quantities corresponding to accidental symmetry will be two components of an equivalent of the Runge-Lenz vector, in addition to one component of the angular momentum vector.

A particle moving under the influence of a constant magnetic field, undergoing cyclotron motion on a circular orbit is another important example of an accidental symmetry.

The energy levels in the hydrogen atom depend only on the principal quantum number n. For a given n, all the states corresponding to

is an essential degeneracy which is present for any central potential, and arises from the absence of a preferred spatial direction.

is often described as an accidental degeneracy, but it can be explained in terms of special symmetries of the Schrödinger equation which are only valid for the hydrogen atom in which the potential energy is given by Coulomb's law.

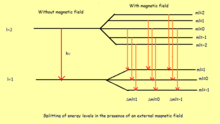

The degeneracy in a quantum mechanical system may be removed if the underlying symmetry is broken by an external perturbation.

The correct basis to choose is one that diagonalizes the perturbation Hamiltonian within the degenerate subspace.

The N eigenvalues obtained by solving this equation give the shifts in the degenerate energy level due to the applied perturbation, while the eigenvectors give the perturbed states in the unperturbed degenerate basis

Some important examples of physical situations where degenerate energy levels of a quantum system are split by the application of an external perturbation are given below.

Examples of two-state systems in which the degeneracy in energy states is broken by the presence of off-diagonal terms in the Hamiltonian resulting from an internal interaction due to an inherent property of the system include: The corrections to the Coulomb interaction between the electron and the proton in a Hydrogen atom due to relativistic motion and spin–orbit coupling result in breaking the degeneracy in energy levels for different values of l corresponding to a single principal quantum number n. The perturbation Hamiltonian due to relativistic correction is given by

The good quantum numbers are n, ℓ, j and mj, and in this basis, the first order energy correction can be shown to be given by

In case of the strong-field Zeeman effect, when the applied field is strong enough, so that the orbital and spin angular momenta decouple, the good quantum numbers are now n, l, ml, and ms.

The splitting of the energy levels of an atom or molecule when subjected to an external electric field is known as the Stark effect.